When Great Britain declared war on Germany a call was sent out to all parts of the British Empire to support their efforts to defeat their opposition. Thousands of miles away in the warm waters of the South Pacific, that call was answered by what must have surely been some of the smallest British Protectorate Nations. Though few in number, they were passionate in their support.

Possibly of all the royal responses in the call of Empire from every habitable portion of the globe, the most unique came from Britain's most distant possessions in the Pacific… First and foremost among these islanders must come the Rarotongans from the Cook Islands, including men from Atiu, Mangaia, Mauke, Aitutaki, Mitiaro, Manihiki, Puka Puka, Penrhyn, and Palmerston… better material for conversion into soldiers could not be found.

Lt-Col J.L. Sleeman in The War Effort of New Zealand, 1923.

With the declaration of war the Cook Islands, like all the other Pacific Nations, were excluded from volunteering for service, as the British Army refused to allow coloured soldiers to fight, in an attempt to protect them from exploitation. So at first, their gesture of loyalty was exhibited through the donation of funds throughout the islands. Mangaia, an island of only 1200 raised £117, which was the equivalent of a day's pay for every woman, man and child on the island. Sir Maui Pomare, the Minister of the Cook Islands at the time, stated in Parliament that is was "unique evidence of the wonderful unity and loyalty of the greatest Empire the world has ever seen."

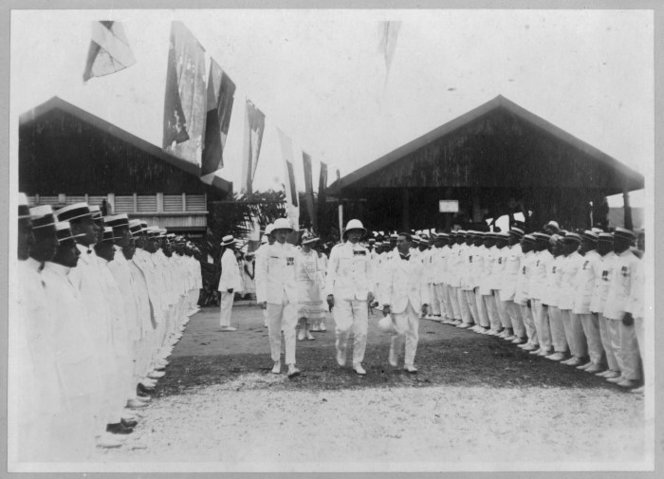

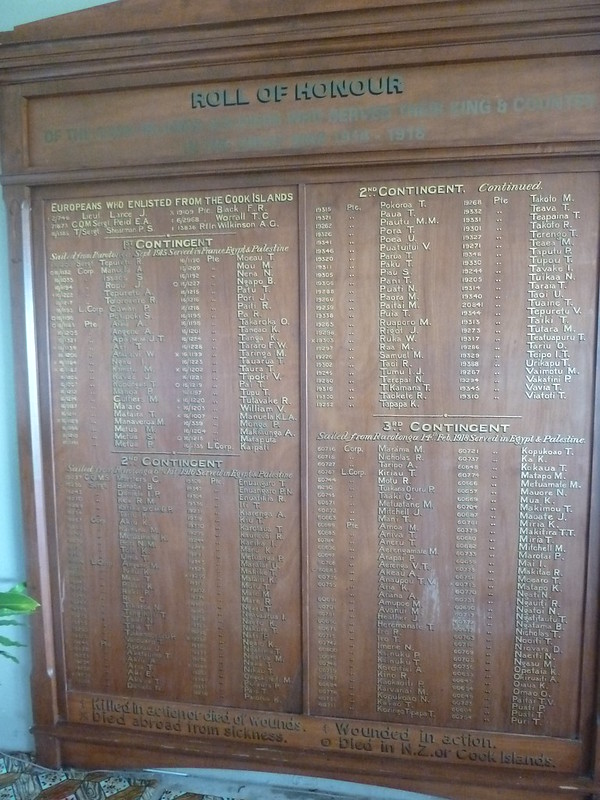

After further pressure to recruit for what was expected to be a lengthy war, the initial pledge for Rarotongan soldiers was accepted. In September 1915, 47 Rarotongans were enlisted and were sent to Narrow Neck Camp in Auckland to train, and spent a month in Egypt before being posted to the Western Front.

Like their Niuean counterparts, 80% of the soldiers could not speak English, but were able to communicate loosely with the New Zealand Māori soldiers. The Cook Island soldiers were also unused to military attire, particularly the boots, and a stodgy military diet. The French winter was extremely harsh on their health, and digging the trenches in the Battle of Somme, under heavy shelling, gas attacks, and sporadic plane bombings saw a great many losses. Eight of those first volunteers died of sickness, one NCO Corporal Apu Tepuretu was shot in action, and one died of wounds.

Major Peter Buck (Te Rangi Hiroa) of the Māori Contingent commended the Rarotongans, claiming they worked "especially well."

As the war waged on, recruiting took place in New Zealand and across the British Pacific Islands. Sir Maui Pomare, desperate to send reinforcements to the Native Contingent overseas, reduced the enlistment age in the Cook Islands to 18 years old and the height restriction was reduced to 5 foot 2 inches. The minimum age in New Zealand remained at 20 years old. The reduction of the age meant that school-aged boys were enlisting without parental permission.

There were also rumours of punishments being issued if able-bodied men of certain parts of the Islands did not enlist. This began to leave a sour taste in the mouths of the Rarotongans. The recruitment drive was pushed to the outlying Cook Islands. More than half of the soldiers that saw active service were recruited from the outer islands of Mauke, Aitutake, Manihiki, Atiu, Puka Puka, the Society Islands and the Tuamotu Group. Across all of the Cook Islands there were 500 in total, 5.8 percent of the population at the time.

The Rarotongans served with great distinction in the Middle East war zone. They gained a reputation for their well-disciplined behaviour. There were several incidents when British soldiers had deliberately ill-treated a Polynesian soldier, but who were then defended by an NCO of the New Zealand Expeditionary Force.

It appears that British soldiers, judging by the colour, do not realise the status of these Rarotongans. The majority of these boys have been College bred… In New Zealand they are treated as white people are. They would naturally resent being shoved to one side, and told, 'Get out you black bugger!'" - Colonel C. E. R. Mackesy

They became renowned for their work ethic, setting new standards of speed and stamina, and the soldiers took huge pride in any job assigned to them. At the first landing of El Arish, "thirty islanders did the work of 170 British soldiers." They were admired for their physical strength and endurance manning ammunition depots. It was here in the depots that Sergeant George Karika earned the Distinguished Conduct Medal for leading his Rarotongan Platoon, to fearlessly load 8 inch, 300lb howitzer shells alongside British gunners.

It is not known how many Rarotongan lives were lost overall. During a Parliamentary questioning on the Rarotongan and Niuean loss of life during the war, Sir Maui reported, "they must have lost upwards of 150 by the war." There were no further details given and no further questioning.

Rarotongan soldiers were quarantined on Somes Island in New Zealand after the Talune ship had carried the Spanish Influenza to the Pacific Islands, and the great Rarotongan war hero George Karika was mistakenly listed as being Tongan.

Despite their war efforts being largely forgotten by New Zealand for a long time, and a lack of true figures of death as a result of war-related illness, the Rarotongan participation in the war was proof that they could forge an independent identity abroad. The soldiers returned home and pushed for better equality in terms of pay and employment, and highlighted the ill-treatment of their people by missionaries, New Zealand administrators, and the Seamen Unions. The returned soldiers became pivotal in the restoration of justice and equality for all of their people.

Jan-Hai Te Ratana

Further reading

- The War Effort of New Zealand: A Popular History of Minor Campaigns in Which New Zealanders Took Part, Services Not Dealt With in the Campaign Volumes

- Years of the Pooh-bah: A Cook Islands History

Online resources

- Pacific Islanders in the NZEF

- Medal citation for Pa George Karika, New Zealand Rarotongan Company

- Unknown Anzacs: Cook Islanders at war from Radio New Zealand

- Flickr Images of War memorials in Rarotonga