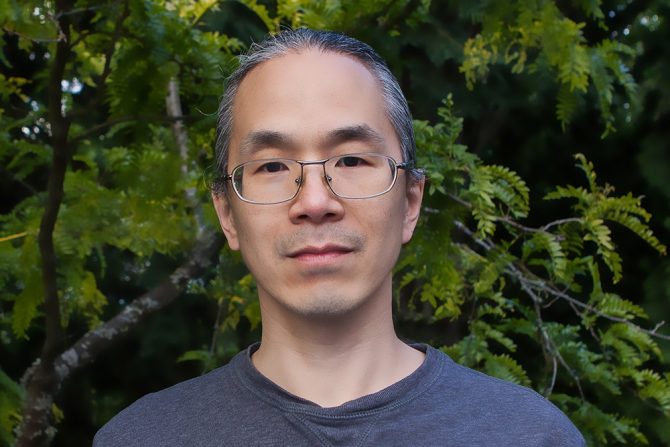

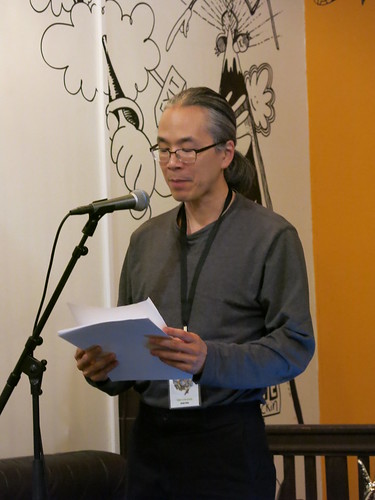

American science fiction writer Ted Chiang has a very particular way of speaking. He pauses a lot to gather his thoughts, and the intonation, or melody, of his voice doesn't vary much. This can have the effect of making it feel that he is taking a very long time to get to the point. Fortunately, Arrival is the third WORD Christchurch session of his that I'm attending so I've become somewhat accustomed to it. Because once you get past the quality of his voice, he actually does have some interesting things to say.

It also helps that Arrival (the only sci-fi movie I've every watched with a middle-aged female linguist as its hero - feel free to recommend others if you know of any) is a recent favourite of mine, and that I'm part way through reading The story of your life, the novella on which the movie is based.

Local sci-fi and fantasy author, Karen Healey happily lets Chiang talk about the things that interest him about the genre he writes in. You get the impression from Ted Chiang that he spends a lot of time thinking generally, and about science fiction especially, so his thoughts, when he does finally express them are fully-formed. His lines are not throwaway ones. He's considered these things from a variety of angles.

For instance, he rejects the notion that his writing "transcends genre", as, in his opinion, this is the kind of thing that people who don't usually like science fiction say - the implication being that the rest of the genre isn't very good, and that this thing that they somehow like is some kind of aberration.

Hollywood sci-fi vs literary sci-fi

I especially enjoy hearing about his views on the nature of science fiction storytelling in movies versus in fiction because, as a fan of sci-fi cinema, I recognise that his observations have the unerring ring of truth to them and I may never watch an MCU movie in the same way again.

In Hollywood sci-fi, he says, there's very often a good vs. evil scenario in which the world is in a good/peaceful/stable state then something evil/monstrous/destructive comes along and there is a struggle to overcome this force of evil and return the world to a state of goodness, peace, and harmony. It's a very conservative formula in that it's looking to restore the status quo. This immediately makes me think of Make America Great Again (MAGA) and just how powerful narratives that resonate with people can be. Human beings love stories and we like to use the same patterns of story over and over again.

The kind of science fiction that Chiang is interested in is entirely different. In these kinds of stories the world is changed by some kind of disruption or discovery and the change is irrevocable. There is no going back to the way things were before. At the end of the story the world is a very different place from what it was at the beginning, and more than that it's not necessarily a better place, just a different one. This is a much more progressive storyline and one that you don't get much in Hollywood movies, if for no other reason than that they are not easy to make a sequel to.

For instance, all the Jurassic Park franchise (currently on its 5th film - a 6th is planned) needs for there to be another dinosaurs-cause-chaos story is for some scientists to make the same errors of judgement the first lot did and the "oh no, who could have foreseen this dinosaur-related catastrophe happening again?" scenario can and will happen again.

Compare this with Chiang's favourite science fiction film, The Matrix. In many ways it looks like a battle between good vs. evil story but it's not. The world is a radically different place at the end of the movie. "Neo's monologue at the very end of the film," says Chiang "has really stuck with me". And just in case we didn't believe him, he quotes it, word for word:

I know you're out there. I can feel you now. I know that you're afraid... you're afraid of us. You're afraid of change. I don't know the future. I didn't come here to tell you how this is going to end. I came here to tell you how it's going to begin. I'm going to hang up this phone, and then I'm going to show these people what you don't want them to see. I'm going to show them a world without you. A world without rules and controls, without borders or boundaries. A world where anything is possible. Where we go from there is a choice I leave to you.

To Chiang this quote perfectly captures what it is to be a radical or a revolutionary. It is not the status quo and it is not comforting, which good vs. evil stories often are. Ted Chiang is not interested in writing "comforting" fiction.

Humanity, curiosity and evidence

What he is interested in is what it means to be human and for him a sense of curiosity, which Healey points out is often present in his characters, is essential.

To be fully human is to be actively engaged with the world around us...

Trying to learn more about the universe is a really noble pursuit and "profoundly meaningful". And though a lot of his stories have a theoretical question or "though experiment" at their core he feels that science fiction, by tying these ideas to a character with an emotional storyline, can make them more accessible to people.

Philosophy doesn't have to be so radically removed from our lived experience. I think it's interesting because it does apply to our lived experience.

Chiang is an Atheist but has an interest in religion. In one of his stories he imagines a world in which there is irrefutable evidence of the existence of God and explores whether that would make it easier or harder to have faith. In some ways, he thinks it would be harder.

In response to a question from Healey about how you approach people from the past as a topic for science fiction, Chiang is magnanimous - people in the past had a different way of viewing the world. Given the observations they had at the time, their interpretations often make sense. Subsequent observations can change this view, of course. They were engaged in the same general practise as modern scientists are engaged in.

It was perhaps this train of conversation that prompted the first of the audience questions, as a very forthright arm shot up a couple of rows in front of me, and an older gentleman asked what Chiang's thoughts were on the question of "settled science", a phrase that he felt was being used to shut down debate in such areas as Climate Change (a topic, it should be noted, on which the vast majority of the scientific community is in agreement).

Chiang, as is his habit, takes a while to get to the point of his answer but to summarise it is basically this: Science is practised by human beings who have biases, but scientists are far more aware of their biases than other people (in particular, politicians, who are the worst at recognising their own vested interests). Science fiction in general aligns with scientists. And science by its nature doesn't really get to an end point.

This is so successfully diplomatic a response that the questioner, judging by the nodding of his head, felt he was being agreed with. Sir, you were not being agreed with. You were being disagreed with in a slow, patient manner.

Movies again

The only other audience question was, shockingly, about science fiction and picked up on Chiang's earlier discussion of The Matrix, which the audience member wondering what he made of the sequels. Like most of us, he found them disappointing calling them "the prime example of the harmful effects" of Hollywood's demand for sequels, when "commerce runs counter to artistic goals".

Which led nicely into a discussion of how the film Arrival got made.

The movie's genesis was rather different route than what's usual, as the screenwriter Eric Heisserer had read Chiang's story and wanted to adapt it, but then had to find someone to produce it. Chiang is at pains to point out that Heisserer deserves all the credit for making The Story of your life work as a movie, as Chiang himself considered it "unfilmable" due to its very "internal" nature. And Chiang himself offered a few comments on the screenplay but mostly stayed out of it.

The movie-making business is so, so weird and it's not something I want to be closely involved in.

Diversity in science fiction

Chiang is happy about the shift in science fiction that has seen increasing diversity in its authors and writing, though this hasn't been without its conflicts, Chiang describing sci-fi's "own version of the Alt-Right" laying seige to the Hugo Awards for a number of years. These efforts, in his opinion, have ultimately proved unsuccessful. N. K. Jemisin, a queer, African-American woman winning the Hugo for best novel for an unprecedented three years running.

Chiang also points out that the popularity of The three body problem by Cixin Liu, a work translated into English from Chinese, is another example of a growning openness in science fiction.

I think it's great because for a long time science fiction, despite it being very forward looking - in practice it's been very conservative.

Not to mention the tropes. So. Many. Tropes. And conventions and little in-jokes. Science fiction, Chiang seems to be saying, in some quarters has become unchallenging and... comfortable.

I very much want [science fiction] to be filled with surprising reading experiences. I think science fiction should be about questioning your assumptions... It should make you wonder about things you took for granted, things you assumed to be true but actually are just a societal convention.

The more different science fiction writers there are, he says, the more likely it is that you get that experience.

And there he goes again, advocating against the status quo. Ted Chiang: the slow-spoken, thoughtful revolutionary.

Add a comment to: Ted Chiang – Arrival: WORD Christchurch