In 1917 and early 1918, the H1N1 strain of influenza swept the world, reaching New Zealand in early summer. It was carried home by soldiers returning from Europe at the end of the First World War. Over 8,000 people died.

The influenza epidemic became New Zealand’s forgotten disaster, as people tried to forget the horror of the First World War. Healthy adults proved particularly vulnerable while the young and old, with weaker systems, seemed to have a better chance of survival.

![Throat spray [1918]](https://christchurchcitylibraries.com/Heritage/Photos/Disc18/IMG0052.jpg)

The pandemic begins

The 1918 epidemic appears to have had its source in Haskell County, Kansas. It spread through military recruits and thence to the European theatre of war. Halfway through the elaborate burial service of the first soldier-victim at Ede, Holland, the bugler playing the Last Post collapsed. The military chaplain said gravely: My friends, this is the first. Which of us will be the next?

1. A medic saw men

… literally choking to death with pulmonary oedema, the lungs so swamped with blood, foam and mucus that the faces were grey and the lips purple, and each desperate breath was like the quacking of a duck 2.

War helps the spread

The Great War was not the cause but a complicating factor in the advance of the plague. Soldiers weakened by mustard gas, shell-shock, injury and illness were being sent to field hospitals or their homes. This population was susceptible to and could easily spread influenza.

The Armistice was signed at a time when the illness was most rife, and excited civilians revelled in what became dance-of-death celebrations. 3

Calling it names

To Spaniards the epidemic was ‘the Naples soldier’4, to Germans it was the ‘blitz katarrh’5 and to the Japanese, ‘wrestler’s fever’ 6. English soldiers fighting in France used the term ‘Flanders grippe’ 7, while in Hong Kong, Western wits mimicked the pidgin English of the bazaars and used the term ‘the-too-muchee-hot-inside-sickness’ 8.

Each country blamed the illness on other nations but, eventually, the name ‘Spanish flu’ was adopted by all. The reason for the name can be readily traced. Nations at war practised censorship, but Spain, a neutral country, did not. It reported the epidemic in detail, especially when, in May, King Alfonso XIII became ill. Thus was the myth born that the plague originated in Spain 9.

The image of a woman to personify a disease or pandemic dates back to medieval and, perhaps, classical times 10. When disease struck Russia, which had pulled out of the war, a Pravda journalist commented: Ispanka [the Spanish lady] is in town

11. Perhaps the journalist knew and was making an oblique reference to the traditional Irish song, ‘The Spanish lady’. However, this woman, who washed and dried her feet, in public, by candlelight, at midnight, would seem to have been eccentric rather than malevolent 12. The epidemic inspired a children’s skipping rope song:

I had a little bird.

Its name was Enza.

I opened up the window

and in-flu-enza. 13

Influenza reaches New Zealand

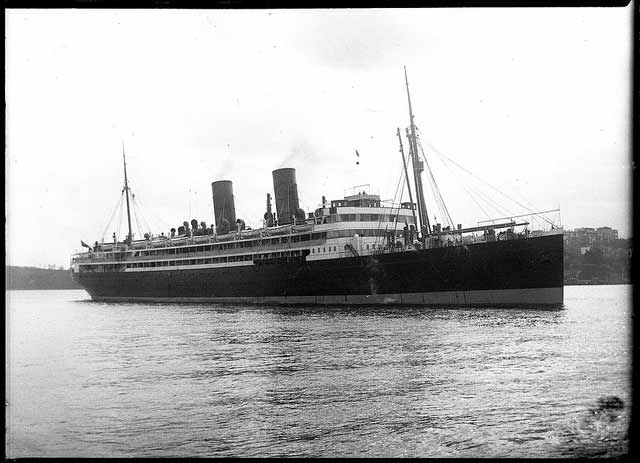

By mid-November 1918, influenza had gripped New Zealand. Which ship carried the deadly flu to this country has never been proved conclusively.

The Niagara often gets the blame. The Niagara sailed from North America and, on 12 October, docked in Auckland. She carried soldiers and civilians, including Prime Minister William Massey and his deputy, Sir Joseph Ward. It was widely believed that the vessel introduced a new, septic and pneumonic

form of the influenza virus to which the population had no immunity; that the use of quarantine regulations could have prevented this; and that, on the instruction of his political superiors, Public Health minister George Warren Russell allowed passengers to disembark 14.

In fact, the Niagara berthed well before the arrival of virulent influenza. Neither Massey nor Ward sought preferential treatment. Of its complement, only a few succumbed.

In October, six other troopships brought soldiers home. Influenza has an incubation period of about 48 hours, yet in Auckland it was a fortnight, and elsewhere a month, before the plague reached its peak. Bacteriologist Robert Mackgill argued that the plague was the result not of a new super-flu but of a mutation in the existing disease 15.

The infection spreads

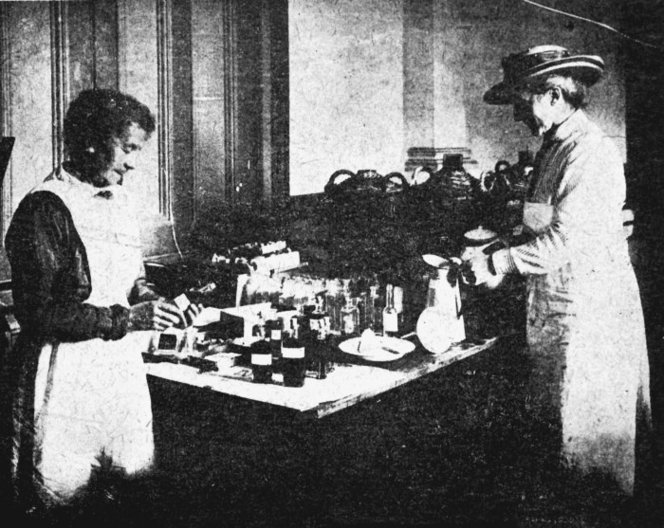

By November there were reports of outbreaks of flu in other parts of New Zealand. But the Department of Health still had not restricted travel around the country, and the infection kept spreading. People came down with the symptoms of the flu very quickly, sometimes collapsing within a matter of hours, and even dying the same day. The only way to avoid catching the virus was by keeping out of contact with other people. There were no flu vaccinations available, and no antibiotics for those who fell ill.

One of the worst effects of the influenza was on the lungs, which could lead to pneumonia, and, more often than not, death. Infected patients found it hard to breathe, and often there was not enough oxygen in their blood. Because of this some of the victims turned a purple-black in colour after they died.

Inhalation chambers were set up so that people could breathe in fumes which were supposed to help clear their lungs. This method of prevention was not proved to be effective, and by bringing people together, it may have helped spread the infection.

Between one third and one half of the population of New Zealand was infected with the flu. In some places the death rate was as high as 80% of the town’s population, while in others there were very few deaths. Military camps, where the soldiers were crammed together in their living quarters, had higher death rates than places where living conditions were less cramped.

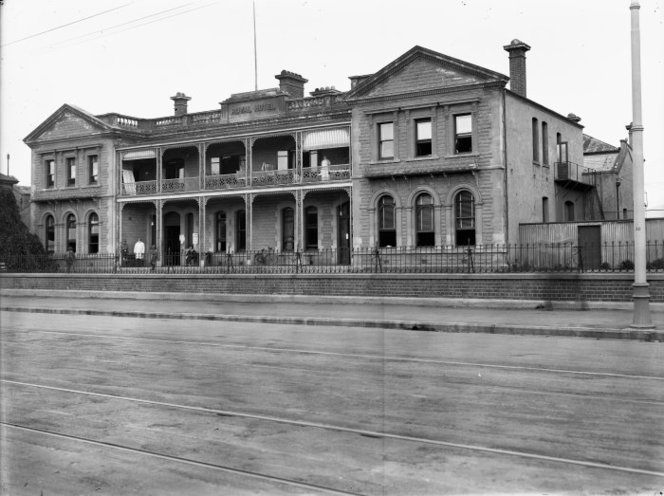

Many doctors and nurses had been overseas with the military forces, and went they came back home several fell ill themselves. Medical supplies began to run low. Hospitals became full very quickly, and emergency hospitals were set up in schools and church halls, and even in tents in some places. Soup kitchens were organised to feed those people unable to help themselves.

The health czar

Because senior health officials were overseas or sick, Christchurch politician ‘Ricketty’ Russell, aging but feisty and capable, became health czar.

He co-opted the Defence Department which established temporary hospitals and sent medical teams to badly-hit areas. Russell’s November 12 telegram to all local authorities set out a practical system of relief organisation for them to adopt. Six days earlier he had declared influenza a notifiable infectious disease, meaning that district health authorities could use special powers to deal appropriately with persons, places, ships, animals or things

16.

Influenza in major centres

In Auckland, officials tried to restrict the spread of disease by closing public venues and keeping people at home. In Wellington, the attempt to maintain an appearance of normality meant that such places often remained open 17. In Christchurch, schools and picture theatres were closed. However, no attempt was made to screen ferry passengers from the North Island who came to attend Show Week, the races and associated festivities.

On 12 November the Armistice was celebrated in Cathedral Square and Dunedin’s Octagon; in both centres, the casualties mounted 18.

Christchurch folk were, as with people elsewhere, sprayed with zinc sulphate. Unique to Christchurch was the way that tramcars were parked and people instructed to pass through them, on the way being sprayed by the concoction. The medical profession remained divided as to whether the inhalation method was of value. Find out more about how Christchurch coped with the epidemic

Influenza in the countryside

The celebrations in Christchurch caused the epidemic to spread south. In the small towns of Canterbury, as in Christchurch, volunteers did sterling work. Three men - George Judson and Messrs Uden and Goodman - did the heavy laundry at the Temuka Influenza Hospital, freeing up women for nursing duties.

![Men doing the laundry [1918]](https://christchurchcitylibraries.com/Heritage/Photos/Disc6/IMG0097.jpg)

Epidemic reaches its height

At the height of the epidemic in November, for 2-3 weeks, ordinary life was impossible. Shops, offices and factories shut down without enough staff to keep them going, and schools, hotels and theatres were closed by order of the government. Because shipping from port to port around New Zealand came to a halt, many towns suffered from a shortage of basic supplies, such as flour and coal.

In some places it became impossible to hold proper funeral services for the victims of the influenza. Many undertakers and grave diggers were ill, and the number of victims too great to deal with. Coffins were made by volunteers.

By December the worst of the epidemic was over, and many who were ill began to recover.

The terrible toll

In all, the official total of deaths from the 1918 influenza epidemic (including New Zealand troops overseas) was 8,573 from a population of 1,150,509.

With some advance warning, preparation and organisation, Christchurch came off better than Auckland and Wellington (4.9 deaths per 1000 versus 7.6 for Auckland and 7.9 for Wellington). Doctors and nurses were among those who lost their lives. At least 14 doctors died from the flu.

The influenza took a terrible toll on Māori. Over 2,160 died (a death rate of 42.3 per 1000 compared with the European rate of 5.5. per 1000). The Māori settlement of Arowhenua near Temuka had 9 deaths out of a population of 130, a rate of 69.2 deaths per 1000).

The Epidemic Commission

G. W. Russell demanded that there be 'the most open inquiry' 19 on the epidemic. A royal commission, commonly known as the Epidemic Commission, met. Its report, which was made public on 18 June 1919, acknowledged that the department was understaffed; nevertheless, it thought bureaucrats slow in reacting to the crisis.

As NZ Truth put it: the graves of many victims of the dreadful scourge are the monuments of incompetence

20. Bowing to public pressure, the commission accepted that the arrival of the Niagara was a substantial factor in the introduction of the epidemic…

21.

Aftermath

Retired judge Sir John Denniston, chair of the Epidemic Commission, suffered an attack of pleurisy and died of pneumonia in July 1919.

G. W. (Ricketty) Russell, once the darling of Christchurch’s eastern suburbs, lost the Avon seat in the November 1919 general election. For the rest of his long life (he died in 1937), Russell defended his and his department’s conduct during the crisis.

As a result of the Epidemic Commission in 1919;there were major reforms in the health system, the most important being the 1920 Health Act.

This was the world’s worst recorded pandemic of influenza, in just four months killing more than 25 million people, or over twice the number killed in the fighting of the First World War. The other major disease epidemic in history was the Black Death of the fourteenth century, in which an estimated 55 million people died of bubonic plague in the course of four years.

The influenza epidemic became New Zealand’s forgotten disaster, as people tried to forget the horror of the First World War.

More information and sources

Search our catalogue

-

Resources about the Influenza Epidemic, 1918-1919

Resources about the Influenza Epidemic, 1918-1919

- Influenza epidemic, First World War teaching resource booklist

- Plague of the Spanish lady Richard Collier

- New Zealand shipwrecks: over 200 years of disasters at sea C. W. N. Ingram

- Book of New Zealand women Charlotte Macdonald, (ed.)

- Black Flu 1918: The Story of New Zealand's Worst Public Health Disaster Geoffrey Rice

- Pale Rider: The Spanish Flu of 1918 and How It Changed the World Laura Spinney

On our website

- 1918 Influenza epidemic - How Christchurch coped

- Dr Geoffrey Rice's list of the names of all Christchurch and Lyttelton victims of the 1918 Influenza Pandemic [130KB PDF]

- Dr Margaret Cruickshank who died during the epidemic

- Dr Charles Little who died during the epidemic

- Go to our page about New Zealand disasters

- Diseases in the news

Online resources

- Influenza epidemic image gallery, DigitalNZ

- 1918 Influenza pandemic, NZ History

- Epidemics - The Influenza era, Te Ara

- Online Reading Room: Influenza articles from The (U.S.) Navy Department Library

- Kai Tiaki: the journal of the nurses of New Zealand

- 1918 flu epidemic – Wikipedia

- Papers past

Footnotes

- 1. Richard Collier, Plague of the Spanish lady, 1974, p 9-10

- 2. Richard Collier, Plague of the Spanish lady, 1974, p 9-10

- 3. Geoffrey Rice, Black November, 2005

- 4. Richard Collier, Plague of the Spanish lady

- 5. Richard Collier, Plague of the Spanish lady

- 6. Richard Collier, Plague of the Spanish lady

- 7. Richard Collier, Plague of the Spanish lady

- 8. Richard Collier, Plague of the Spanish lady

- 9. 1918 flu epidemic – Wikipedia

- 10. Information from Geoffrey Rice, Professor of History, University of Canterbury, 14 July 2011

- 11. In search of an enigma : the Spanish lady, Mill Hill Essay

- 12. Lyrics to ‘Spanish lady’: http://www.barbarygrant.com/Lyrics/Brigit/spanish_lady.htm

- 13. Rod Daniels, '“… In flew enza”: the 1918 influenza epidemic',Naval History and Heritage Command library website [now removed]

- 14. Geoffrey Rice, Black November, 2005, p. 63-70, 184-201, 250

- 15. Geoffrey Rice, Black November, 2005, p. 63-70, 184-201, 250

- 16. Geoffrey Rice, George Warren Russell – Biography from the Dictionary of New Zealand Biography. Te Ara Encyclopaedia of New Zealand

- 17. Geoffrey Rice, Black November, 2005, p. 66-89, 90-114

- 18. Geoffrey Rice, Black November, 2005, p 115-140

- 19. Geoffrey Rice, Black November, 2005, p 242

- 20. Geoffrey Rice, Black November, 2005, p 246;

- 21. ‘The Epidemic Commission. Will ‘Ricketty’ Russell resign?’, NZ Truth, 28 June 1919 p 1