In November 1918 Christchurch, like most New Zealand towns and cities, was affected by the influenza pandemic sweeping the world. Normal life was disrupted and by the time the epidemic had passed 462 people had died (out of a population of 92,773). In 2018, Dr Geoffrey Rice updated the list of the names of all Christchurch and Lyttelton victims. His book Black November gave the total number of deaths as 458, but his recent research has discovered two Māori victims at Rapaki and two other deaths of Christchurch people elsewhere.

How did the city cope with such a wave of illness and death?

The arrival and spread of the influenza

The deadly influenza strain’s arrival is sometimes attributed to the Union Steam Ship Company’s Niagara, which arrived in Auckland in October 1918. However there were dozens of ships arriving from Europe and North America at this time.

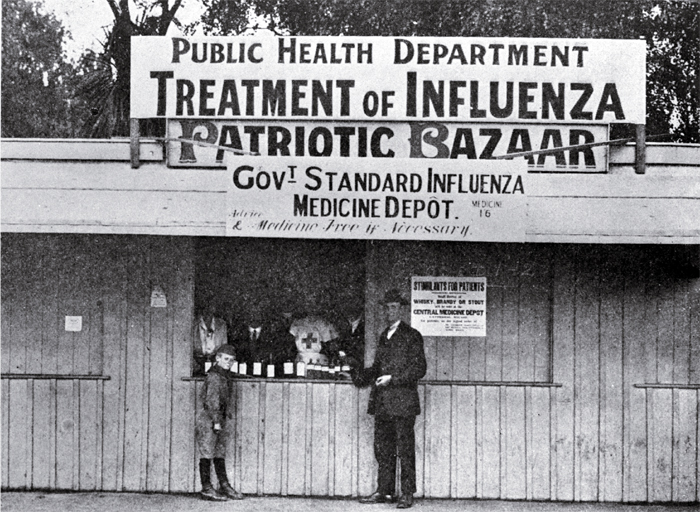

Authorities in Christchurch were aware of the development of flu in the North Island. The district health officer, Dr Herbert Chesson, had one small steam inhalation apparatus which was sent to Lyttelton to be used to spray passengers from the inter-island ferries with zinc sulphate. He ordered the closure of schools, theatres and other places of entertainment, asked chemists to extend their opening hours into the evenings and the police to enforce by-laws against spitting in public.

On Friday, November 8, People’s Day at the show went ahead. It was also known as the day of the false armistice and impromptu celebrations went ahead to mark the end of the First World War. When the official Armistice news arrived on November 12, celebrations and parades went ahead in the city, attracting large crowds. Show Week and the crowded celebrations helped the flu to spread through the city and on to other towns in the regions.

Inhalation centres established

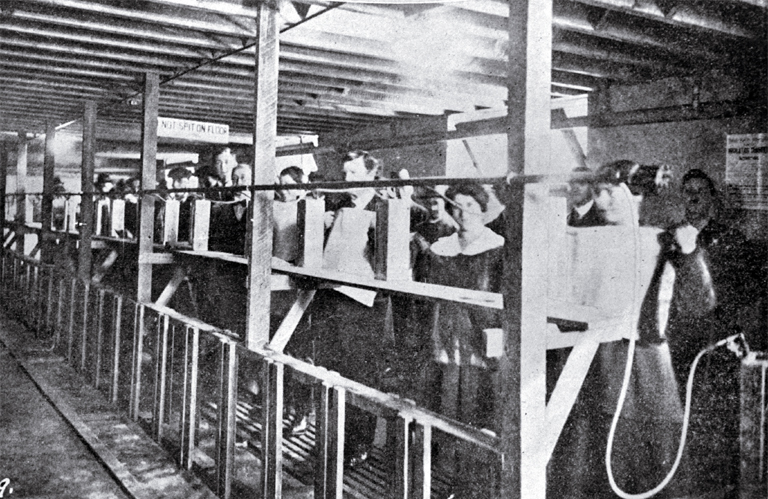

Christchurch began to establish inhalation centres, spraying zinc sulphate, believed to help prevent infection. The first was upstairs in the Electricity Department building in Manchester Street. This was an unsatisfactory venue because of congestion on the stairs so a centre was established in the large brick shed across the street. A chamber was opened to the public in the Government Building in Worcester Street.

Six trams were adapted and began operation on November 12. People walked through the clouds of vapour inside the tram. Eventually 14 trams were in operation serving outlying suburbs.

Advice from the New Brighton Borough Council

The public are advised that the use of the inhalation chamber should not be availed by those who have developed symptoms. The inhalation chamber is situated at the terminus opposite the café and is open from 8 a.m. to 9 p.m.

Epidemic spreads quickly

By November 14, Christchurch Hospital had 145 flu admissions, doubling admission numbers in just three days. Many nurses were infected and the hospital was organised to run with a large number of volunteers. All the serious flu cases in the city were directed to the hospital and over half of all the city’s flu victims died there. 722 patients were admitted during the epidemic of whom 232 died.

The Press reported on November 19 that there were 2550 cases of flu of which 192 were acute or serious.

Dr Chesson also established a central convalescent hospital at the Addington Trotting Ground using the tea rooms which were spacious and well lit with a large kitchen and ample toilet facilities. They housed up to a peak of 97 patients on December 1. Nurses lived in the members grandstand and the male orderlies slept under the main grandstand. Gas stoves were installed for extra water heating and temporary showers erected.

Nurse Maude leads relief efforts

Christchurch launched a relief organisation on November 14. Nurse Sybilla Maude was put in charge of a central depot in Cathedral Square. Nurse Maude was famous for her district nursing organisation in the city.

The city was organised into blocks, a system already familiar through Red Cross war-time fundraising appeals. Volunteers systematically canvassed houses to find people who were ill. A food distribution system was instigated using depots around the city. Doctors were rostered to visit the depots daily to collect the names of cases to visit.

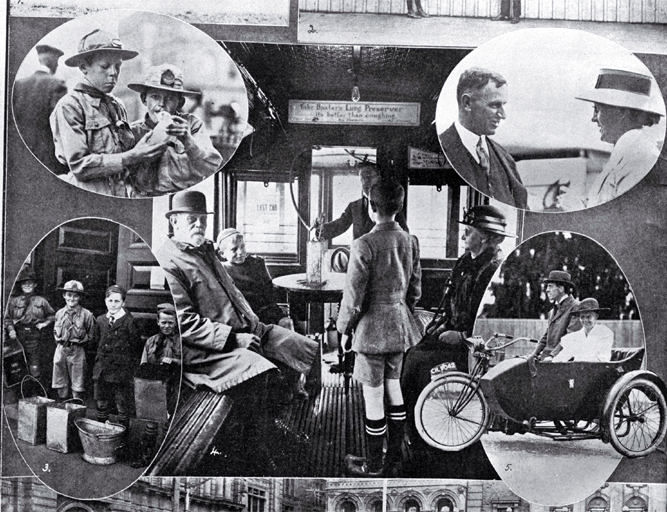

Private cars and commercial vans ferried food from the kitchens to the depots for distribution to homes using cars, motorcycle sidecars, bicycles and Boy Scouts with baskets.

Provision needed to be made for the care of children whose parents were stricken with the flu. The Karitane Hospital in Cashmere was made available for small babies, Bishopscourt in Park Terrace and a large house in Bealey Avenue belonging to Mrs F. H. Pyne catered for older children. Sydenham Park was used as a supervised playground catering for 300 children a day.

Epidemic wanes by early December

In Christchurch the epidemic declined sharply after several weeks and by December 7 the central medicine depot closed. The Cathedral choir resumed normal practices on December 3 and the depots and kitchens closed down over the next two weeks.

In the aftermath of the epidemic leading relief organisations, Nurse Maude, the Automobile Association, the Boy Scouts and the St John Ambulance Brigade were acknowledged. These groups had provided and organised many of the volunteers including 200 St John trained nurses at hospitals and convalescent hospitals.

Influenza’s terrible toll

In all the official total of deaths from the 1918 influenza epidemic (including New Zealand troops overseas) was 8,573 from a population of 1,150,509. With some advance warning, preparation and organisation, Christchurch came off better than Auckland and Wellington. (4.9 deaths per 1000 versus 7.6 for Auckland and 7.9 for Wellington). Doctors and nurses were among those who lost their lives (At least 14 doctors died from the flu).

In Canterbury, grateful citizens built memorials to commemorate Dr Margaret Cruickshank (in Waimate) and Dr Charles Little and his wife Hephzibah (in Waikari). The Nurses’ Memorial Chapel, Christchurch Hospital, commemorates epidemic victims Grace Beswick and Hilda Hooker, as well as nurses who died in the sinking of the World War I troopship the Marquette.

More information

In our catalogue

- Search for Influenza Epidemic 1918-1919

- Search for Influenza Epidemic 1918-1919 New Zealand

- Black November; the 1918 influenza pandemic in New Zealand. Geoffrey W. Rice

- It’s in The Press; 140 years of writing from Canterbury’s newspaper

On our website

- 1918 Influenza Pandemic About the Influenza pandemic of 1918 and its effects on New Zealand

- Dr Margaret Cruickshank who died during the epidemic

- Dr Charles Little who died during the epidemic

- Nurse Sybilla Maude who organised nursing services during the epidemic

- A small gallery of photographs from our collection

Local newspapers

Some historic Canterbury newspapers are available online via Papers Past

These titles and and issues of The Weekly Press and The Lyttelton Times for this period can be viewed on microfilm on Tuakiri | Identity, Level 2, Tūranga.

Online resources

- The 1918 flu pandemic NZ History

- Christchurch in the 1918 Influenza Epidemic: A preliminary study Dr Geoffrey Rice

- Dr Geoffrey Rice's list of the names of all Christchurch and Lyttelton victims of the 1918 Influenza Pandemic [130KB PDF]

- Margaret Cruickshank - Dictionary of National Biography

- Christchurch Hospital Nurses' Memorial Chapel