Today, when you stand at the intersection of Kilmore Street and Park Terrace and look westward across the Avon River you are greeted with the expanse of North Hagley Park. Designated as an arena for special events, the grounds usually remain empty save for the occasional cyclist or runner who might pass by. The only disruption to this tranquil scene is the traffic of Park Terrace.

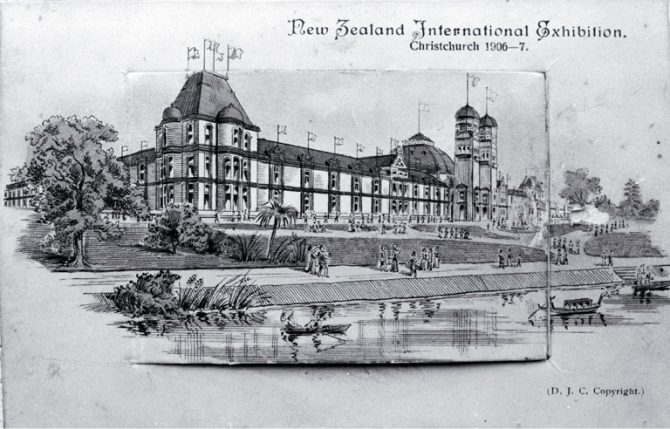

Yet if you were to have stood in the same location over a hundred years ago, you would have been met by a very different sight. Set before the length of Park Terrace you would have found a gleaming white building styled in the manner of the French Renaissance with towers topped by golden cupolas. From across the river there would have drifted a mixture of noise; music, children shouting, camels growling and even the sounds of an American Civil War battle.

This was the 1906 New Zealand International Exhibition.

Opening on 1 November 1906, the exhibition was an opportunity for the Liberal Government, led by Premier Richard Seddon, to proclaim to the world the technological and social achievements that had been developed in New Zealand. By the time the exhibition closed on 15 April 1907 up to two million people had visited, almost twice the population of the entire country.

Welcome to the Exhibition

In a city devoid of high rise buildings, the towers of the exhibition could be seen from across Christchurch, drawing people to its main gate at the end of Kilmore Street. After paying for a ticket and passing beneath a sign which proclaimed “Haere Mai”, visitors would cross a bridge spanning the Avon River. There they would find themselves standing amid carefully planned lawn gardens where they would decide whether to venture into the impressive building before them, or, perhaps if they were accompanied by children, to proceed to the various forms of entertainment that were to be found in the surrounding grounds.

If the grand Italianate façade proved too alluring, then visitors could ascend the front steps to discover what lay within. There, in the foyer, they could ride an electric elevator to the balcony of the southern tower where they were presented with a view of the city. Proceeding through to the Grand Hall, with its domed ceiling set at a height of 90 feet, visitors would enter the main exhibition hall. Here they would find the multitude of exhibits to which the building was dedicated.

The world in Hagley Park

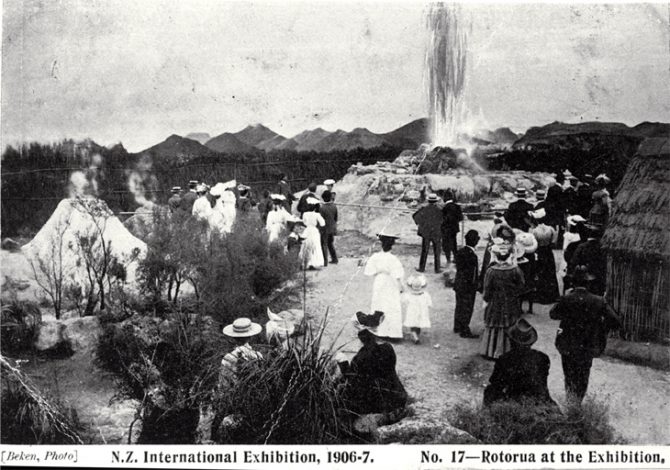

In the machinery hall they could find examples of industrial progress ranging from motor vehicles to ice making machines. The Railway Department exhibit even housed a locomotive engine which had recently been built at the workshops in Addington. In the Department of Tourists and Health Resorts Court, visitors could explore a recreated Rotorua complete with a working geyser, a hot pool and children who would dive for pennies.

The courts dedicated to other imperial colonies allowed visitors to look upon minerals from Canada or purchase table grapes from Australia. In the Art Gallery they could view an extensive collection of British art or find the inspiration to participate in the Arts and Crafts movement. For those whose interest lay in native flora there was the fernery, a circular room with a green tinted glass ceiling where visitors could stroll amidst eighty different species of New Zealand ferns accompanied by waterfalls and pools of trout.

At the concert hall visitors could listen to performances by an orchestra under the direction of conductor Alfred Francis Hill, while moving pictures, a new form of entertainment, could be viewed in the neighbouring Castle Theatre.

Wonderland on Victoria Lake

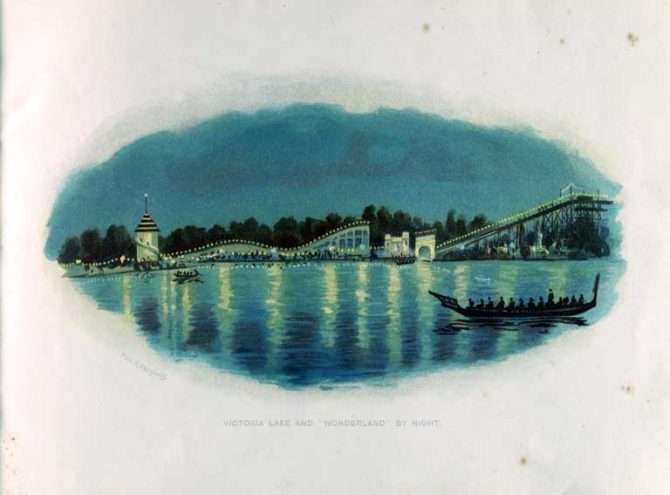

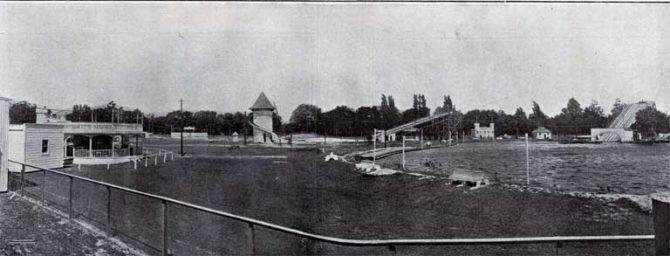

Despite the exhibition’s emphasis on trade, industry and social development, the draw card for many visitors was not the exhibits but the amusements that were to be found in the grounds outside the main building. Scattered around the southern and eastern shores of Lake Victoria was a range of side shows and rides collectively called Wonderland.

The rides included the water chute, a toboggan course, a train designed to look like a dragon, the helter-skelter, a merry-go-round and a gondola which travelled on a pulley rope system. Entering The Pike, visitors were treated to a variety of amusements from penny in the slot machines, the House of Trouble maze, the Rocky Road to Dublin, the Laughing Gallery, to Professor Renno and his Palace of Illusions.

If the visitors were prepared to brave the smell which emanated from a fenced off section of Lake Victoria then there was the opportunity to see seals and penguins which had been imported from Macquarie Island.

Intriguing buildings and structures

One of the largest freestanding buildings constructed for the exhibition, and perhaps the most intriguing, was the Cyclorama. Circular in shape, it featured a 360 degree panoramic painting of the Battle of Gettysburg. Patrons would stand on a display, designed to look like a Civil War battlefield, set in the middle of the room, where they would listen to lectures on the history of the battle, accompanied by visual and sound effects.

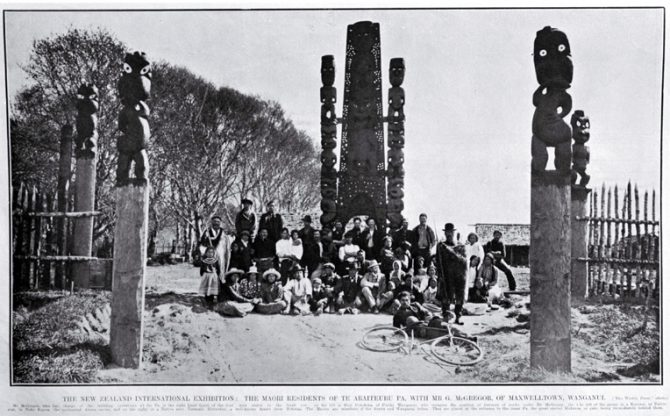

Another structure of note was the replica pā, Te Āraiteuru, at the north-western end of Lake Victoria. Surrounded by a palisade, the pā consisted of a wharenui named Ōhinemutu, twenty whare puni, a set of pātaka and a tohunga’s whare. The idea was to convey to visitors a romantic recreation of a ‘lost’ Māori past. Performers were encouraged to wear ‘authentic’ Māori clothing and to cook their food over open fires. In addition to Māori, there were also performers from Fiji (who put on a display of fire walking), Cook Island Māori, and Niueans.

For all their grandeur the buildings were never intended for permanent use. Their deconstruction commenced following the closure of the exhibition in April 1907. Throughout the year the site of the former exhibition still continued to attract visitors as much of the building material retrieved was either sold as firewood or auctioned for reuse. In another instance, crowds gathered to watch as the towers from which they had once looked out over their city were brought crashing to the ground.

One of the few buildings left intact was a prefabricated two storey workers’ cottage, designed by Samuel Hurst Seager and Cecil Wood to showcase the improvements in living and working conditions for workers that had been made by the Department of Labour. Since it was ready for inhabitation, the cottage was relocated and today it now stands at 52 Longfellow Street.

Elements of Te Āraiteuru also managed to survive. The meeting house is now on display at the Linden Museum in Stuttgart, Germany, while the carvings, after spending years in storage at Canterbury Museum, were eventually returned to their region of origin, Taranaki. The waharoa or carved gateway now resides at Te Papa Tongarewa.

Although nothing now remains of the former exhibition, the next time you find yourself standing on the shores of Victoria Lake, pause for a moment to imagine the sights you may have encountered had you stood in the same location on a summer’s afternoon in 1906.

Add a comment to: 110 years ago: The 1906 New Zealand International Exhibition