By the 1860s the newly-minted city of Christchurch was attempting to stand on its own two feet (figuratively speaking) with the passing of bylaws intended to regulate the lives of the citizenry living, dying and engaging in commerce and other nefarious activities within the confines of the four avenues.

A handbook for coroners

The New Zealand Government was doing its bit with legislation designed to conform to British standards of jurisprudence but with a local flavour. One such example was the Coroners’ Act of 1867 which regulated the coronial investigation into sudden or accidental deaths. A vital publication of the time was A Handy Book for the Coroners of New Zealand, written by Alexander J. Johnston, Judge of the Supreme Court of New Zealand, and published in 1868.

This useful little book, sized to slip easily into a pocket for handy reference, set out to explain the ramifications of the new act for coroners and other concerned persons, and also provided a number of handy forms to be used in the furthering of the coronial inquest.

Coroners were appointed to inquire into the manner of the death of any person who was slain or drowned, who died suddenly or in prison or while detained in a lunatic asylum, and whose body was found “lying dead”. They also had jurisdiction to investigate the cause and origin of any fire that destroyed a building or a ship, merchandise, stacks of corn or hay, or any growing crop.

With the investigation of a death, the desired outcome was not so very different from those of today’s courts – finding out the identity of the body, how they died and who was culpable, and enlisting the efforts of a jury of 12 men to do so. But a close examination of the handy forms reveals a rather different approach in the community as to what constituted murder.

Killed someone? There's a form for that

There are several entries and forms under the heading “Excusable Homicide”. This includes “Killing by Correction” i.e. when a master accidentally kills his apprentice with a too vigorous beating, or when a parent does the same to their child. And “One Child Killing Another by a Knife in Play”, which is self-explanatory, if horrifying to conclude that it was a common enough occurrence to warrant a separate form. And you could be excused if you killed someone while defending your property in a riot.

“Justifiable Homicide” covered a court-imposed execution, and also if you happened to kill a highway robber. “Killing by Necessity for Self-Preservation” was excusable, as in if you happened to survive a shipwreck, and found yourself clinging to a piece of flotsam alongside another person, if the plank or whatever could not save both of you, you could force the other person off into the water with no legal consequences (so Rose could have PUSHED Jack off into the water in the movie Titanic, and it would have been legal (in New Zealand waters). Shocking!).

And “Accidental and Casual Death” included the phrase found frequently in newspaper headlines of the time – “Found Drowned - Person Unknown”. More forms were provided to cover if someone drowned in attempting to cross a river, or died by starvation, by explosion of a steam engine, or by the fright of a horse.

The role of the constabulary (lights out at 9.30pm)

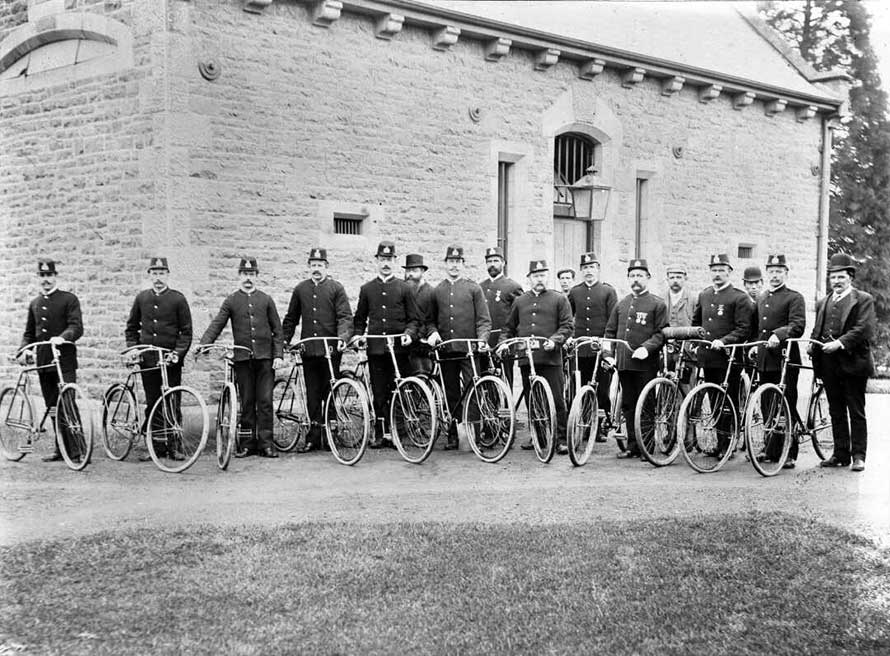

But in order to instigate an inquest, the local constabulary had to do their job. Fortunately, the official duties for the police of Canterbury were detailed in yet another handy pocket-sized book, titled Manual of Police Regulations for the Guidance of the Canterbury Constabulary Force, published in 1862.

The most important duty of all members of the police force was “the prevention of crime, protection of person and property and the preservation of public tranquillity”. So not so very different from today’s desirable outcomes. And the members of the constabulary were to be “of active, energetic, and temperate habits, of unimpeachable honesty, and must discharge their duty on all occasions, independently, uprightly, and conscientiously”. And in their spare time they were encouraged to improve their mind with reading and writing, and lead a sober and steady life. They would have been queuing in their hundreds to join up.

The constable’s duties included arresting without warrant every common prostitute wandering in the street and behaving “in a riotous and indecent manner”, which would have kept them pretty busy, but in addition to that constables had to discourage beggars, wilful exposure in any public place, singing of obscene songs in the hearing of passers-by, and the ill-treatment of animals. They also were directed to caution any person bathing in that part of the river reserved for the public water supply, and report anyone throwing offal, carrion, or other offensive material into the water supply. And of course, they couldn’t enter a public house except in execution of their duties.

To stay awake and alert on duty constables were sent to bed at 9.30 at night and made to get up at 5.30 in the morning in summer. They were allowed an extra hour sleep-in in the winter. And their sergeants were required to make inspections of the barracks during the night to check that all the constables were in their beds.

But at least a constable patrolling on foot was issued with a rifle and sword, a baton, handcuffs, pouch and belt, rattle, dark lantern and something listed as a “number”, as well as two pairs of trousers, one pair of white gloves and other items of clothing. And your own uniform box painted “stone colour” to keep everything in. If you were one of the mounted constabulary you were given a revolver instead of the rifle, but you did have to ensure that your horse did not travel at a pace exceeding five miles an hour, except in an emergency.

And if a constable was uncertain of the seriousness of a crime, there was a handy list at the back of the manual which detailed whether an act was a misdemeanour or a felony. So “forcible abduction for motives of lucre” was a felony, but “abduction of a girl under 16 years” was just a misdemeanour. As was scoffing at scripture, disinterring and selling a dead body, not repairing a bridge, or disturbing a congregation of Dissenters. A felony was pretty well any form of deliberate fire in those days of inadequate fire-fighting resources, but also child stealing or attempting to destroy a building with gunpowder, or throwing a stone upon a railway carriage with intent, and many more.

Citizens contemplating a criminal act would have been well advised to ask their local bobby to check for possible consequences of that act in his manual of regulations.

Find out more

- If you’re interested in finding real examples of misdemeanours and felonies, take a look at some issues of the Canterbury Police Gazette or read Glenn's post Crimes of the 19th century: Canterbury Police Gazette

- Note that A Handy Book for the Coroners of New Zealand is available online as part of the Early Books New Zealand Project

Further Reading on the history of the New Zealand Police:

- Policing the Colonial Frontier: the Theory and Practice of Coercive Social and Racial Control in New Zealand, 1767-1867 Richard S. Hill

- The Colonial Frontier Tamed: New Zealand Policing in Transition, 1867-1886

- The Iron Hand in Velvet Glove: the Modernisation of Policing in New Zealand, 1886-1917

- Sharing the Challenge: a Social and Pictorial History of the Christchurch Police District

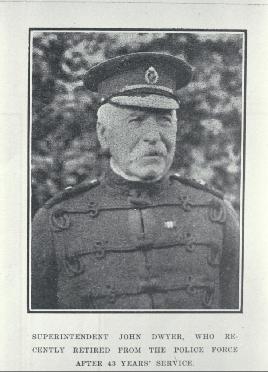

- For a first-hand account of policing Christchurch later in the 19th century try Fragments From the Official Career of John Dwyer, Superintendent of Police, 1878 to 1921

Annette Williams | Family History Librarian

Tuakiri | Identity Team, Tūranga

Add a comment to: A Handy Guide to Surviving and Dying Within the Law in 1860s Christchurch