A city without power

The month of June 1918 started pleasantly enough for Canterbury. However, as the weeks progressed, the good weather soon gave way to frequent rain. By 27 June, snow had started to fall in the back country. Then, on the afternoon of Sunday 30 June, the temperature in Christchurch plummeted and the sky darkened. Snow fell on the city, but did not settle. Soon it was replaced by rain which continued to fall throughout the evening.

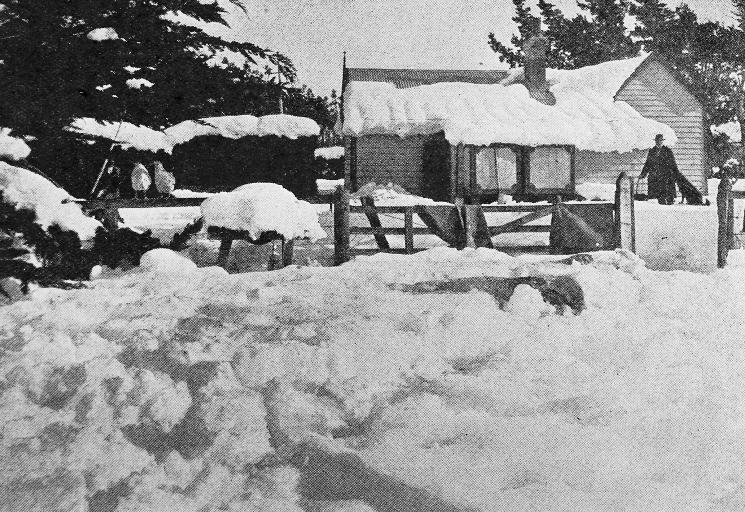

Further inland, the snow kept falling. As it steadily built up, the weight of it caused the chimneys and roofs of rural houses to collapse. Livestock which couldn’t find shelter were buried. Telegraph lines were bent. The railway lines became completely snowed under, with the West Coast train stuck at Waddington.

Canterbury was completely cut off from the rest of the country.

Throughout the day the power in Christchurch began to falter. Then, at 3.50pm, the south transmission line from the hydroelectric scheme at Lake Coleridge failed.

Monday 1 July

When the people of Christchurch awoke on Monday morning they found that the city was cut off from its main power supply. Throughout the night, attempts had been made to repair the south transmission line, but by 2.40am it had failed. This was followed at 6am, with power failures on the north transmission line.

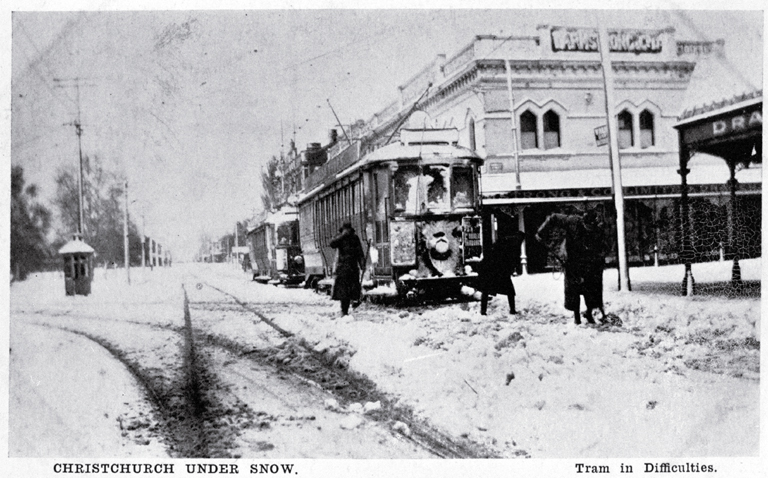

The Tramway Board and the City Council municipal plants were able to supply a limited amount of power to the city, using coal provided by local coal merchants and the Railway Department. Yet the restricted amount caused the power to remain intermittent.

Lawrence Birks, the Public Works Department (PWD) Chief Electrical Engineer for Canterbury aimed to establish where the breaks had occurred on the north and south transmission lines, and began to organise for men to get through to the power house at Lake Coleridge.

Tuesday 2 July

The superintendent at the Lake Coleridge power house was Archibald George Rennie Blackwood. Realising that Christchurch was without power, he set out, with a couple of workers, using a dray drawn by two horses, hoping to find the location of the fault in the transmission lines. After an accident forced them to leave the dray behind, they continued on through the snow with the horses. Eventually they reached Snowden Hut, where they camped for the night.

Meanwhile, an attempt to establish communication with the rural township of Coalgate was made by PWD employee, Robert Allen. Setting out on foot from Darfield, he staggered through the snow and managed to reach his destination, exhausted.

Another attempt was also made by Harold and William Jones. Travelling in a motorcycle with a side car, they departed the Addington substation at midday and reached Hororata by 2pm. Despite being warned to turn back, they pushed on. As the evening approached, with the intention of reaching Snowdon, the brothers were overtaken by two PWD cars. One of the cars had been fitted with a snow plough, but was soon forced to turn back. The other contained another PWD employee, Boris Daniels.

The brothers soon found that the wheels of their motorcycle were hindered by the ruts left behind by the PWD car’s snow plough. After attempting to push the motorcycle, they were forced to discard it and continue on foot. Wading through three miles of deep snow, they finally reached Hororata at 10pm, where they were put up for the night.

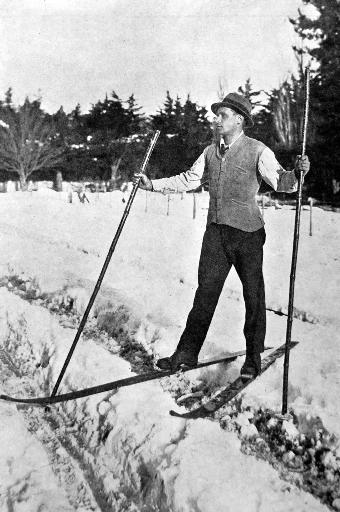

Meanwhile Boris Daniels, after overtaking the two brothers in the PWD car, had reached Hororata at 6pm. A Russian, he had been loaned a pair of skis which had formerly belonged to Robert Falcon Scott. Setting out immediately, he reached Mount Hutt, where he rested, having been forbidden by Birks from continuing on through the night.

Wednesday 3 July

The next morning, with their clothes still damp, Harold and William Jones made the return journey back to their motorcycle. Since the ruts which had previously impeded them were now filled with frozen water, they were able to return to Hororata. However, upon arriving, they learned that Boris Daniels had already set off, with the likelihood of reaching Lake Coleridge.

Earlier that morning, Blackwood, the power house superintendent, and his men had also left Snowden Hut, reaching Point Hut by midday.

Having set out on his skis, Boris Daniels found himself confronted by a vast, white landscape. In many places the snow was three feet deep, allowing him to simply jump over any fences which normally would have been a barrier. Throughout his journey, he encountered sheep which, without any shelter, had become buried, the only sign that they were still alive being their noses poking through the snow. When he reached Brackendale Hut, he was met by two men on horses who had been trying to reach Lake Coleridge but to no avail. Continuing onwards, he finally encountered Blackwood and the team from the power house at the line’s highest point. Together, they returned to Brackendale Hut and spent the night in a nearby farm house.

From Christchurch, another attempt was made, with three PWD cars setting out in the morning and one in the afternoon. The last car contained G.F. Ferguson, the assistant engineer of the Lake Coleridge scheme, C.P. Agar, and two journalists. Upon reaching Hororata, they found that the other cars which had preceded them had been abandoned. Continuing on to Coalgate, the depth of the snow meant that they often had to get out and push the vehicle. Eventually they reached their destination where, after a meal, they ventured out into the frozen night on foot to examine the damaged lines.

Thursday 4 July

With only a sporadic amount of electricity to rely on, Christchurch had been brought to a near standstill. Factories were unable to operate effectively to meet production deadlines. Workers were sent home. The trams which were able to run did so with no lighting. Businesses whose trading hours normally extended into the evening were forced to close. When the automatic stoker of the Tramway plant failed, the workers resorted to manual hand stoking and using inferior coal, which caused a reduction in the pressure.

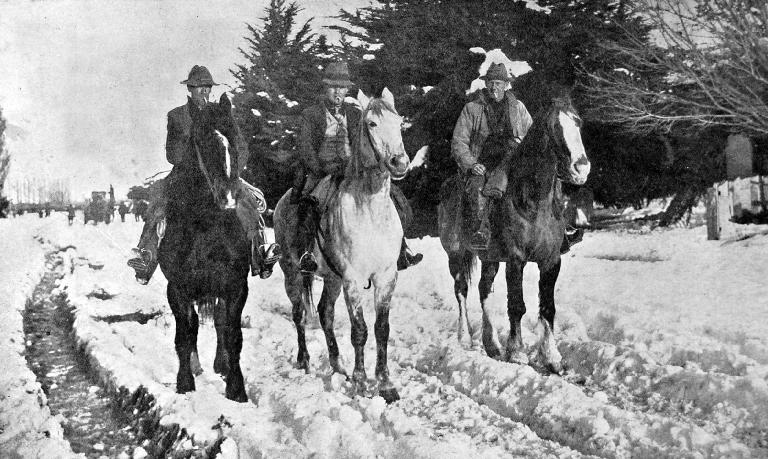

On Thursday morning, G.F. Ferguson, C.P. Agar. J. Reeves and R. Young set out from Coalgate for Lake Coleridge on horses. By midday they had reached the house of Mr and Mrs Gilmour, who insisted that the party stay for lunch. Afterwards, the group pushed on to Round Stables Hut. The plan was that, if the lake power house was still out of contact, they would then proceed with a nocturnal march across the frozen snow.

However, upon reaching Round Stables Hut, they managed to make contact with the power house, only to learn that another group, which had reached Hawkins Hut, had beaten them by mere minutes.

As the repair teams started to fix the transmission lines, they found that the weight of the snow had caused the poles to bend and break. Because the current couldn’t be turned on until it was certain that the damaged isolators had been replaced and that the repair gangs were clear of the lines, it wasn’t until 8pm that they could start testing the lines.

Friday 5 July

By 10pm Friday, power had finally been restored to Christchurch, allowing for communication with Wellington to be established via the West Coast. However, eighteen miles of telegraph line between Christchurch and Kaikoura still remained damaged. Smaller townships such as Waikari, Hawarden, Culverden and Waiau would remain isolated until 12 July.

Over the following days, life returned to normal for the people of Christchurch. Many may have rushed to purchase the Delco-Light electric generators from the Farmers store, which took advantage of the situation to advertise their stock. Yet for many, although they had experienced late trams, closed shops, and a lack of lighting, the loss of these conveniences was not as nearly as distressing as the absence of the news regarding the war in Europe.

Find out more

- An account of the snowfall in The Press 5 July 1918.

- An account of the snowfall in The Press 6 July 1918.

- Advertisement for Delco-Light generators.

Add a comment to: Coalgate or bust! The great snow of 1918