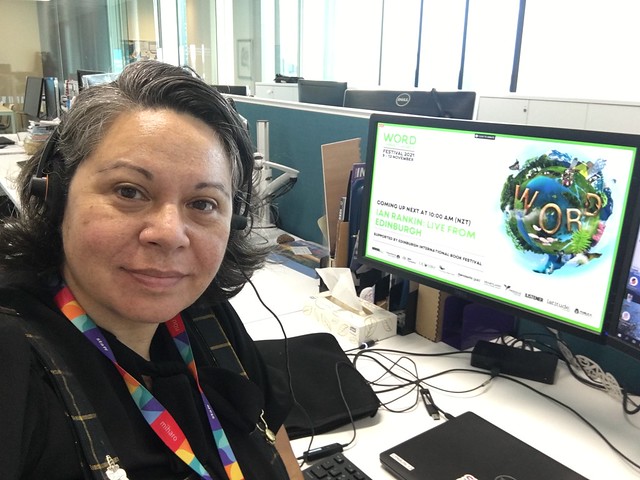

Logged in with headphones on. This is the new way of literary festivals in the time of Covid-19 - livestreaming international authors into your living room or office. Or physically distanced in an auditorium with an author talking head looming over proceedings like Big Brother. Or as Vanda Symon exclaims at crime writer Ian Rankin, "Crikey you're large!"

Symon is seated on stage at The Piano, oddly, with a vacant seat and microphone to her left. Who is the second seat for, ghost Ian Rankin? But as with all good mysteries, things will become clear in the fullness of time.

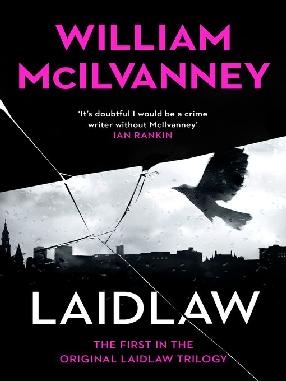

Symon and Rankin are "there"* to talk about his latest book, The Dark Remains - the book was started by fellow Scots crime writer, William McIllvanney and left uncompleted when he died in 2015 and is a 4th chapter in McIlvanney's Laidlaw series.

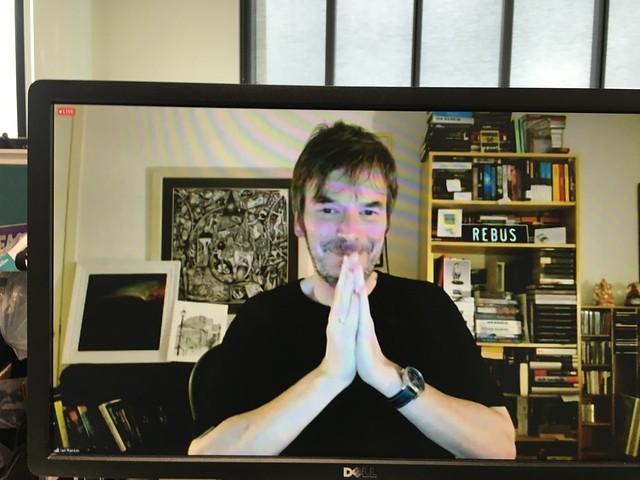

Ian Rankin greets us from his home office by way of raising his can of beer to the camera, and we're told it's from a Dundee brewery. So far, so Scottish.

When you buy a ticket to a literary festival session with a particular author, it's not usual to expect so much of the session to be spent waxing lyrical about an another author entirely but this is how much of this session goes. This is not a complaint. Rankin is a garrulous enthusiast of probably many things, but certainly he's very happy to spend time explaining how great William McIlvanney was.

Scottish crime fiction

In McIlvanney Rankin saw a model of what was possible in terms of writing crime fiction at a time when Scottish crime fiction wasn't the publishing powerhouse it is today. McIlvanney had been an author of literary fiction (and therefore a serious writer) who later wrote crime fiction in the form of his Laidlaw novels. "He made it okay to writer crime fiction," says Rankin and off the back of McIlvanney's Laidlaw, Rankin's protagonist John Rebus was born.

Rankin tells the story of approaching McIlvanney at a literary festival event and explaining that he had just written a book (not yet published at that point) that was a bit like Laidlaw but in Edinburgh. McIlvanney signed his book with "good luck with the Edinburgh Laidlaw", possibly expecting never to hear of this person ever again. Later he describes McIlvanney as sort of a mentor. McIlvaney, he says, was intelligent, funny, with a self-deprecating sense of humour, and "film-star good looks - he looked like Clark Gable" as well as being "a lovely, warm guy".

Rankin tells the story of approaching McIlvanney at a literary festival event and explaining that he had just written a book (not yet published at that point) that was a bit like Laidlaw but in Edinburgh. McIlvanney signed his book with "good luck with the Edinburgh Laidlaw", possibly expecting never to hear of this person ever again. Later he describes McIlvanney as sort of a mentor. McIlvaney, he says, was intelligent, funny, with a self-deprecating sense of humour, and "film-star good looks - he looked like Clark Gable" as well as being "a lovely, warm guy".

Whereas these days Scottish crime fiction seems like a fait accompli, as if it has always existed, Rankin is quick to point out that this wasn't always the case. Certainly there was a tradition of Scottish literature like Robert Louis Stevenson's Jekyll and Hyde, and the work of Arthur Conan Doyle, but Doyle "ran away" and never came back, "He chose to set his books in London".

As well as McIlvanney's Laidlaw Rankin picks Trainspotting as "a shot in the arm" for Scottish fiction and part of a "renaissance" for Scottish literature. These were both examples of writing that was about the working class, urban experience, books that were about politics, social issues and the state of the world "but also why human beings all across the globe continue to do terrible things to each other."

But back to Scottish crime fiction, sometimes known as "Tartan Noir". Rankin laughingly holds up his hand as the originator of that term. When asked to define it he says, "it's a lazy term I guess..." pointing out that it really encompasses quite a range of fiction from cosy mysteries to the harder and darker and more gothic end of things like the work of Denise Mina and Val McDermid.

The two faces of Edinburgh

Rankin, as many writers are, is enamoured of his home city, not least because it's home to so many creative people and writers, namechecking Alexander McCall Smith, Kate Atkinson, and J. K. Rowling as writers who at one point were all living within a walkable distance of each other.

But he also appreciates it for less seemly reasons. Edinburgh, he says, is one thing on the surface but something else underneath. This is an idea he comes back to, this idea of unearthing and revealing things in the manner of an archaeologist.

The gothic thing is there. At night it can feel like it's the 17th century.... you can feel that you've gone back 300 years in history. It shows you one face and hides another face. A bit like Dunedin, Vanda.

Or perhaps it's more Jekyll and Hyde, one personality for the day time and another for night. Bag pipes and castles for the tourists in the daylight, and something more sinister by streetlight.

On finishing someone else's book

Naturally conversation turned to how Rankin had come to finish McIlvanney's book and the challenges that posed.

Rankin was suggested for the project by McIlvanney's widow, Siobhan, and was given a collection of papers, handwritten notes (a thick stack of which he flicked through on camera) that were a mixture of things, some character sketches and other ideas. They were the beginnings of two books McIlvanney had planned, one a prequel to the first Laidlaw book, the other a final instalment which presumably were intended to bookend the series.

Rankin describes the process of finding the book in amongst these notes as like that of an archeologist "brushing delicately around each part" going so far as to mime the action with an invisible brush in his hand. It wasn't until after he'd looked at the collection of notes that Siobhan asked him if he'd like to take on the job of finishing the book and "...that was when I took a sharp intake of breath..."

Rankin was able to pick out the thread of a story for the prequel book, though there were was no ending. There was a post-script scene and epilogue but no climactic scene.

I sort of felt that I knew where he wanted it to go and I just had to figure out how to do it.

From there Rankin agreed to give it a go but if he got stuck with it or didn't think he could make a decent job of it he reserved the right (literally, in the contract with the publisher) to back away from it.

Rankin describes McIlvanney's writing as very poetic and so there was a challenge in trying to match that writing style, "trying to be a ventriloquist" which is not something he's done before. Other authors have though. Rankin references Raymond Chandler's final Philip Marlowe novel, Poodle Springs, which was later finished by Raymond B. Parker (and a local example is Money in the morgue, an unfinished Ngaio Marsh Roderick Alleyn novel completed by Stella Duffy and published in 2018).

To get it right Rankin did a "deep dive" back into McIlvanney's work, but also researched what was happening in Glasgow in 1972, the setting for the book. How old was the character then? How was the city different?

Luckily for Rankin it all happened during lockdown. He had just finished A song for dark times and didn't have much else to do.

Luckily for Rankin it all happened during lockdown. He had just finished A song for dark times and didn't have much else to do.

I can't go anywhere... pubs aren't open... cinemas, shops aren't open - oh, someone's given me a job, great...

Although Rankin admits, "I didn't want to tinker with Willie's world too much", notes back from the publisher mentioned the lack of strong female characters and the propensity for scenes to feature hard men sitting in smoky pubs outstaunching each other. Which, yes, that's what happens in the Laidlaw books. As a result he added more women and pulled the characters out of those smokey pub settings (sometimes putting them in cars instead). So the resulting novel is possibly a bit more modern but a bit less of a Laidlaw book.

Later on he reflects that the earlier setting made it less of a slog in a way, because of the absence of technology in the early 70s. Cellphones, DNA, CCTV: All great tools for crime-solving. Also tricky things that crime writers have to write their way around. "Why wouldn't that person have just called for help using their cellphone?" is something you have to address in modern crime fiction because readers are smart enough to ask those questions. Rankin admits to being "a lazy writer at heart" so it was quite fun writing in an "a much simpler world".

When asked about the latter novel, snippets of which were in McIlvanney's notes, Rankin says there wasn't enough to pick up on the story. If someone were to write it, it wouldn't be a McIlvanney novel and he's not interested in doing that.

The Glasgow stare

Where Rankin's series is based in Edinburgh, McIlvanney's is set in Glasgow. When asked which is the harder city, Rankin doesn't hesitate: Glasgow, Glasgow, Glasgow.

There's a hardness in the characters, the gangsters and thugs of the Laidlaw novels - macho men, hard men, shaped by experience in a place where you have to be tough to survive.

One of Willie's [McIlvanney's] books starts "Glasgow, the city of the stare"... When you walk into a bar you can't look weak. You have to make an impression that you're not someone to be messed with before you've even got up to the bar.

No one has yet called him out on getting Glasgow wrong which he seems grateful for, though he briefly plays with the idea of claiming of any error that "that was Willie's bit" before quickly backpedalling with "no, you can't defame the dead".

When comparing Glasgow to Edinburgh, he says that the latter has "invisible crime" perpetrated by those in banking, the corporate world, government. White collar swindlers who will cheat people out of more money than any number of gangsters or thugs could ever steal.

A lot of what happens in Edinburgh happens below the surface. It's happening behind windows and doors and walls. I like that the violence and crime isn't on the surface and you have to dig quite deep to find it.

The future for Rebus

Symon wonders who Rankin would pick to complete his unfinished work if he were to die suddenly. Rankin's answer is simple:

The unfinished work is unstarted... The unfinished work consists of a deadline and me panicking.

Rankin jokes that his wife, who asks for regular updates, knows that once it's 150 pages in, "we're past danger point now", meaning that somebody probably could finish it at that point. He says this with a wry, "gallows humour" chuckle.

But sometimes your creation outlives you.

Great characters don't die. Authors die but the characters don't.

Inspector Morse, Sherlock Holmes. They just keep ticking along without any input from their authors.

I can see someone in the future doing "Young Rebus" but I don't know who.

But where might Rebus go in the future? Rankin thinks that there's fun to be had with the aging Rebus trying to come to terms with technology and the rapidly changing world and he admits that "the clock is ticking for Rebus" but he's unsure what to do about it.

If he writes another one should he mention masks, or the pandemic? Or are readers sick of the reality of that? Might it be time to get Rebus into a nursing home?

Murder Island

In the meantime he's had other things to work on including a reality TV show called Murder Island. His pronunciation of the word "murder" prompts Symon to ask him to say it again so he gives it a good old burr doing his best Taggart "Thar's bin a murrdurrr" impression.

Whilst in lockdown a TV company approached him with reality TV concept - a Scottish island (Gigha Island) with a murder, where contestants have to solve the case, with actors playing the suspects. There's a £50 000 prize but the winner has to put together a case that the prosecutor could take to court. Real lawyers and cops oversee and offer assessments. The series has just finished in the UK.

Rankin seems to think the potential is there for a Kiwi version: "you've got plenty of islands".

Question time

At this point, the purposed of the "ghost chair" becomes apparent as question askers are invited to come up and sit in the chair, and therefore be on camera so Rankin can both see them and hear them.

One metre physically distanced queuing ensues.

Rankin is a music fan. Does he have a soundtrack that he listens to while writing?

Yes, and it's the same for all of them - an ambient mix with artists like Tangerine Dream, Brian Eno and listened to at a hardly audible level that "creates a bubble where the world disappears". Rankin can't listen to music with lyrics when writing because he'll get too distracted by it, just instrumentational stuff, some jazz.

Will you retire Rebus?

Rankin doesn't know. He has been resistant to a Young Rebus novel but it was quite fun going back in time with the Laidlaw one so he's considering it, "It depends if the good Lord spares me or not." Meanwhile his wife is keen on him taking time off to travel. "It might be time for me to take my foot off the gas..."

Is Rebus's record collection the same as your record collection?

Possibly not. Rebus doesn't have much after 1975 so he wouldn't be into some of the more modern stuff that Rankin is. But artists like Van Morrison, The Stones, The Who would all be in both. Rankin has to be careful that his taste isn't Rebus's taste because their ages are different and there's stuff Rebus wouldn't have listened to but which Rankin has. "He [Rebus] doesn't get punk. Where I would happily listen to the Ramones, he wouldn't."

Rankin then recounts the time he was invited to make a selection for BBC's Desert Island Discs. He went down to London for the show and out of the 8 albums he'd selected was asked to whittle down to a single one, so he picked Solid Air by John Martyn. At lunch the same day he discovered that seated at the rowdy table at the restaurant was... John Martyn. This was his perfect opportunity to introduce himself, given his reason for being in the city but... he "bottled it".

Still, other musicians have become fans of his books - "every crime writer I know is a frustrated rock star - I've met most of my heroes now - John Martyn is the one that got away".

What's his writing process like? How much does he plan?

It's not like geometry, all plotted and planned.

I almost never know what the ending is going to be.

He doesn't necessarily know who did it or why though he has "an inkling".

The book has a better idea of where it wants to go than I do.

Writers fall into two groups plotters vs pantsers. Rankin is a "pantser" meaning he flies by the seat of his pants.

If I knew what was going to happen in the book why would I be bothered writing the book? I write the book to find out what's going to happen in the book.

When asked if he ever gets stuck the sound of Rankin superstitiously tapping away at the top of his home office desk is very audible. He's says he's never got stuck but sometimes he doesn't know how to get Rebus from one situation to the one he needs to be in for the story so sometimes he'll chat to his wife about it and they bounce it around a bit until there's a solution.

The book is floating around in the ether waiting to be written and you just have to channel it.

He finishes off his answer to this question with a mantra-like "plot will find a way, plot will find a way..."

Would you start a new series with a new character?

He doesn't think so but who knows? He has an idea for a one-off high concept thriller that's "sitting in the big box of ideas". But he needs to make a bit more of a concrete start to something.

I'm literally sitting here with a June deadline for a book that will come out in October next year and I've got nothing... and Christmas is coming.

He claims he's at "the panic attack stage" but that's not bad... except for his blood pressure.

And there so endeth the session. All that remains is to get a review of that beer he's been drinking. It turns out not to be a favourable one:

It's got passionfruit in it... Passionfruit beer from DUNDEE? It should have rusty nails in it.

And for him to say that Christchurch is one of his favourite cities in the world that he hopes to get back to in person (perhaps some travelling with his wife?).

And with a cheery two-handed wave from a home office in Edinburgh the livestream of Ian Rankin ends, a jolly good time had by all (of those not drinking Dundee beer with passionfruit in it).

*Their "theres" are different physical places but they're both on the same screen I'm looking at. There's probably a philosophy essay in the question of what "there" means in this context but I am certainly not the person to write it.

Find more

More WORD Christchurch 2021

- Our WORD Christchurch page

- More WORD Christchurch posts

- WORD Christchurch website (for the full programme and info about authors)

- Follow WORD on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram

Add a comment to: Plot will find a way: Ian Rankin, live from Edinburgh