We celebrate the 130th year of women's suffrage in New Zealand with a series of posts about local suffrage campaigners.

"Courage? Pooh! You men think you have a monopoly of it."

Alice Burn, The Press, 14 April 1894, page 7

Alice Burn, born in South Canterbury in 1871 and very well-known in Christchurch in the 1890s, was certainly courageous. She was not afraid to speak her mind and live her truth, constantly advocating and supporting other women to do the same.

She absolutely believed that women should not be constrained by traditional 19th century gender roles, including the tyranny of long heavy skirts and corsets. Because of this, she became one of our most outspoken dress reform advocates.

She was also…

- A suffragist: She signed both the 1892 suffrage petition as well as the 1893 'monster petition'.

- A public speaker: She roamed New Zealand giving talks about woman’s place in the upcoming 20th century, encouraging women out of the home and into education and employment, into more active and engaged lives.

- A doctor: She graduated from University of Edinburgh in 1906 with a Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery, and later got a Diploma in Public Health.

- A mother: She and her husband David William Murray Burn had one daughter, Valeria Meredith Burn.

- And so much more.

Today I’m just going to focus on two things she was passionate about: pants and bikes!

Cyclist

Alice was an extremely keen cyclist and played a large role in the early days of women’s cycling. The arrival of the safety bicycle in the 1890s made it possible to ride in long skirts and dresses, but even though women could ride, opinions were divided on whether or not they should. Was it proper for a woman to risk showing her ankles? To discover what freedom and speed felt like? To ride around without a chaperone and get up to who knows what?

Alice didn’t give two hoots what people thought she shouldn’t do.

To get more women into cycling, and to make it safer and more fun for those who already were, she proposed the formation of a club. She’d realised, astutely, that women could do more to normalise and promote cycling if they banded together than they could on their own. It was her idea that they take the name Atalanta, after the Greek heroine and huntress, and so in August 1892, the Atalanta Cycling Club was formed. It was the first ladies cycling club in Australasia.

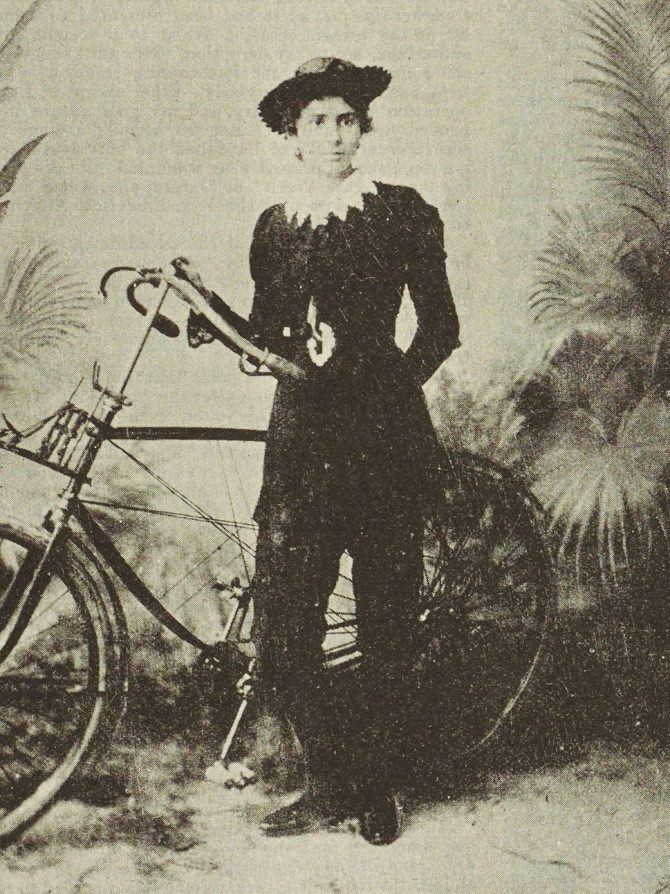

Here’s Alice (image below) when she was about 21, standing second from the right with her bike and a few other members of the club:

For several years, the club grew and the cycling events and outings they held were popular. However, one of the early rules the club adopted was that they must not ride in ‘rational dress’; which meant they had to wear skirts if they were going out in public on their bikes.

Society at the time made many women genuinely afraid that any radical behaviour – like the wearing of pants, or even being in the company of women who dared – might damage their own reputation. This was a self-protective thing; reputation was a vital part of middle-class social life. Behaving out of the norm also put women at risk of physical and verbal abuse; there are stories of people throwing rocks at women for daring to ride a bike.

None of this stopped Alice. She’d learned how much easier cycling (and all manner of sport, though she drew the line at football) was in ‘rationals’ and she wasn’t going back.

Rational dress

Rational or reformed dress, basically, meant freedom from corsets and long, heavy, restrictive dresses. It often meant knickerbockers or a divided skirt; lighter clothes that were comfortable and gave women freedom of movement. It was something Alice had been passionate about since she was a teenager.

In 1893, she wrote:

“We dress reform advocates, despite the persecution of a conventional society, find ourselves so enormously the gainers that we can afford to smile at the short-sighted opposition of today’s majority, that by tomorrow will have dwindled out of sight."

‘Where Women Have Led’, Auckland Star, 31 October 1939, Page 42.

In April 1894, Alice was in her third year attending Canterbury College. She wrote to the Board of Directors asking to be allowed to attend lectures in rational dress, and though she wanted the matter to remain private, the public found out, and letters to the editor in The Press lit up with comments and opinions from both sides of the ongoing ‘how should women dress in public’ debate.

The ruling of the Governors was not in her favour; they claimed that if a woman was to "attend college with her nether extremities openly arrayed in bifurcated garments" it would distract other students. (Oamaru Mail, 11 April 1894, page 2)

One writer for the press, who went by the pen-name ‘Bohemian’, was outspokenly on the College’s side. He was certain that: "parents of ladies attending the College will be very grateful to the Board for supressing with a firm hand this latest outrage on good taste and common decency." (The Press, 7 April 1894, page 7)

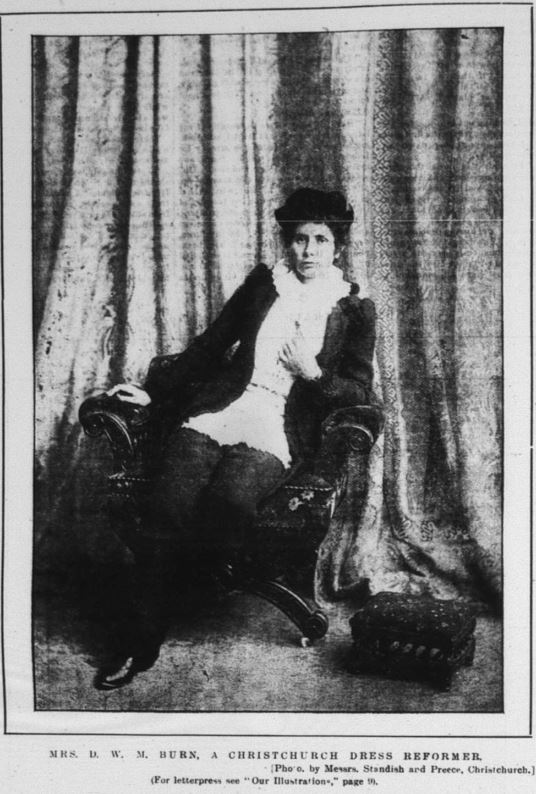

He did, however, seek out Alice the week after to get her opinion. The entire article is well worth a read! (The Press, 14 April 1894, page 7)

He described Alice as an "emancipated woman” who “stood revealed to me in the dress of the future!" In her drawing room, which he described as the cosy nook of an artist and not, as he had feared, the bower of an Amazon, they chatted about their opposing viewpoints. Alice made the point that "the present ideal of woman's dress is the result of a low conception of her place and work in the world" and that conventional clothes are impractical, and “designed to satisfy the eye only.”

I have to wonder, in 2023, what opinions she would have on women’s clothes with fake pockets… Designed to satisfy the eye only indeed.

Though she is not named in this article, all signs point toward it being her. At the end of the interview, she gives ‘Bohemian’ a photograph of herself for publication in the Weekly Press the next week, and sure enough on 26 April 1894 a photo of our Alice appears.

The month after this, in May 1894, Alice founded the New Zealand Rational Dress Association. By then, women had achieved the right to vote, but the fight to choose their own clothes was one that had yet to be won.

Later life

Alice left Canterbury College around this time, and shifted her studies to Otago University instead. It doesn’t look like she ever came back to Christchurch to live.

In 1903 she and her two sisters, Eva and Christina, moved to Edinburgh to study medicine. She took her four-year-old daughter with her and left her husband David behind to live his own life in New Zealand, though by her own words their separation was only a matter of geography, and not because of any ill feelings between the two of them. David and Alice were always on the same wavelength about issues like dress reform and women’s emancipation, and he was quite the character himself, being a poet, a cycling enthusiast, a mystic, a lecturer in philosophy and an ardent Theosophist. In fact, he gives a glowing introduction to the book ‘Notes Dress Reform and What It Implies’ written by one of Alice’s cycling friends, Kate Walker.

Alice’s career in the UK was just as packed as her life in New Zealand. With a long list of medical qualifications and positions throughout the country, she never stopped fighting for equal rights, better health, diet, and clothing for women.

Even during the Second World War, now in her late sixties, Alice offered her medical expertise to the people of Harrow, London. She was given full administration of a first aid post where she had sixteen stations under her care, and the King himself bestowed honours upon her for this.

Dr Alice Burn died at the home of her daughter – now Lady Valeria Meredith Scott – in Northern Ireland, on 10 April 1949.

No mention of her death graced the papers back in New Zealand, but for every convention she threw aside and everything she achieved, she is a woman worth remembering.

Further reading

Find out more

- Take our Women's suffrage quiz

- More posts about suffragists

- Our page on cycling

Alison

Local History Librarian

Add a comment to: Alice Burn: ‘A lady who bids defiance to custom and convention’