Colonial era policing had many challenges. An offender trying to avoid arrest could easily assume an alias or a different name. Identification methods were primitive by today’s standards. Techniques such as mug shot photographs and fingerprinting were still some way off.

So how did the police track down offenders and missing persons?

Painting a picture using words

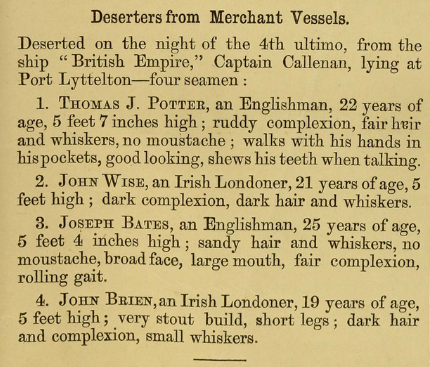

If you browse the lists of wanted persons in the pages of the Canterbury Police Gazettes you’ll be struck by the vivid descriptions of offenders or missing persons. Not only were physical characteristics such as hair colour, eye colour, height, etc revealed but foibles, mannerisms, quirky behaviours were also noted in vivid detail.

Taken together they give a strong sense of the character of the person. No doubt this would have helped the police in identifying the person they were seeking. However, for the contemporary reader it’s hard not to raise an eyebrow or crack a smile when reading them.

Speak of the Devil

Sometimes a description would focus on the offender’s manner of speaking.

Henry Swanson, a deserter from the ship the Monarch while it was docked in Lyttelton in early October 1870 is described as speaking in “an effeminate voice.” Similarly, a warrant was issued in November 1875 for the arrest of Thomas Edwards for fraud offences who talked in a “singing kind of voice”. Edmond Ford, a seaman accused of stealing several rugs from the Eastern Monarch ship in mid-1874 was described as “lisps very much”.

Some offenders were identified not so much by how they spoke but by their fondness for music.

When William Gamble escaped from the hard labour gang at Lyttelton in June 1863 an alert was issued which included a comment that he was “very fond of singing a song called “Highland Mary.” (It would have been interesting to know if his fellow prisoners shared the same affection for this song).

Guilty man walking

Other distinguishing features such as the way in which an offender walked was sometimes highlighted. Robert Lundy, another deserter from the Monarch while berthed at Lyttelton in 1870 is depicted as “a big man, with red moustache and tuft of beard on the chin and walks very slovenly in a stooping rolling gait”. His companion Walter Martin was described as walking “with a stoop and swings his arms in a peculiar manner”.

Smooth criminal

Some offenders were even described in complimentary terms. Charles Larsen, a deserter from the ship, the Stonehouse was presented as having “fair hair, a round smooth face, stout build, well made and rather good looking.”

The shipping news

Details about the person’s immigration to New Zealand were often included in the descriptions. The name of the ship and the year they arrived were frequently included. Perhaps this suggests that the person’s identity was intrinsically linked to the ship he or she came to New Zealand on. After all, it’s reasonable to assume that in a nation of newly arrived immigrants that this would have featured in many conversations.

Clothes maketh the man

Descriptions of clothing worn by wanted persons also figured prominently. Many people living in the colonial era would have owned few clothes so descriptions of various articles of clothing worn by an offender could be useful for identifying the person. For example, John Ecclesfield who had an arrest warrant issued on him on January 1870 is described as being “dressed in tweed coat and trousers, crimean shirt and black billy-cock hat with straw under the brim”.

More about crime in colonial era Christchurch

- Earlier post: Crimes of the 19th century: Canterbury Police Gazette

- Canterbury Police Gazettes

- Canterbury Police Gazettes (a selection covering the years from 1869 to 1871

- Fragments from the official career of John Dwyer, Superintendent of Police, 1878 to 1921

- Christchurch Crimes, 1850-75 Scandal & Skulduggery in Port & Town, Geoffrey Rice

- Christchurch Crimes and Scandals 1876-99, Geoffrey Rice

Add a comment to: Canterbury Colonial Crimewatch