Ottessa Moshfegh is in Amsterdam. We are in Tūranga. But that's how The Faraway Near rolls. Julie Hill is in charge of asking the questions of the Booker-shortlisted novelist.

I'm excited to learn, in Hill's introduction, that Moshfegh's novel, Eileen, is being turned into a film starring Kiwi actor Thomasin Mackenzie. Having read the book, and seen Mackenzie's turn as a fragile, haunted young woman in Edgar Wright's Last night in Soho, I immediately see the canniness of this casting choice.

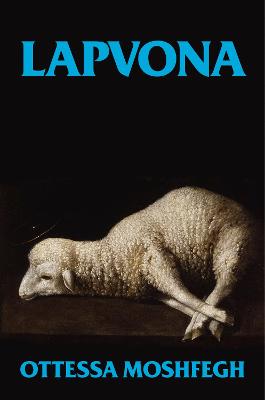

I have not read her latest novel, Lapvona, which is set in medieval times. Moshfegh lays the basic premise out thusly:

It's about a boy who kills another boy (by accident, on purpose) and the dead boy's father decides that the best outcome for everyone (but mostly for himself) is if that boy replaces his dead son.

The father is the local lord. The soon to be adopted son has grown up as the son of a shepherd so it's "a very classic rags to riches scenario". Moshfegh says, "it felt at once whimsical and very, very dark which is exactly the kind of fiction I felt like writing".

In fact, Moshfegh hadn't planned on writing a novel at all in 2020 but "a lot of things didn't go to plan that year..." and writing Lapvona provided "a world to escape into away from what was feeling like the end of the world, as well as the walls of my house day in, day out..."

So far, so relatable.

Hill asks about the quote at the opening of the book, "I feel stupid when I pray", which comes from the Demi Lovato song, Anyone, and Moshfegh talks about watching Lovato's performance at the 2020 Grammys that came following the singer's overdose. In the peformance Lovato starts singing but has to stop because you can hear she's close to crying. They start again and give a really moving performance. Moshfegh admits to being really shocked by it, partly because the nature of live awards shows - what she calls " a very candied world". Moshfegh says she "couldn't forget it" and the idea in the song of "...reaching out into the ether... for some kind of power, strength or hope or anything seemed really radical to see on live television". It was a moment that really stuck with her.

That Lapvona is so focused on the topic of faith probably makes it a fairly apt inclusion too. Moshfegh says it's about "faith and how it functions in an individual, a relationship... a community, and humanity".

This was the first novel that Moshfegh has written in the third person - her other novels, are very much about the interior, "almost monologues". Telling a story from an "omniscient, third person point of view" means that she can know the characters intimately but also "judge them in a way that accumulates throughout the story". This is an idea that she comes back to later in reply to an audience question. With a work like Eileen, or McGlue, for instance:

So much of the work of a writer is figuring out how that character would tell their own story... If there's something to describe in first person the author has to understand what is being observed... and then how would my first person character describe that information?

With third person there's more range in how things could be observed... there's a sense of fraternity or friendship, as though I'm sitting at the table with them and considering them, not BEING them.

She also thinks that the third person allows her to see her characters "more objectively" as well as see "where they came from in me".

There's definitely some of herself in her main character, Marek, who has a similar spinal issue - Moshfegh had scoliosis as an adolescent and wore a back brace. She made a conscious choice to have a character with chronic pain as a way of exploring "what that did or what it does to the psyche". In the case of Marek he is "growing in the wrong direction" both physically and spiritually. He compensates for his feelings of insecurity with his faith - "he believes that the more pain he feels, the closer he is to God."

And then there's his father who tries to access "a higher power via violence". He has what Moshfegh describe as "an amoral sense of faith".

At prompting from Hill, Moshfegh talks about some of the other characters in Lapvona, such as Ina, the elderly wet nurse who is "trying to live an exalted life" and whose close relationship with nature develops into super human powers.

Of Villiam, Marek's adopted father, and the lord of Lapvona, she says he's delusional and he's surrounded by people who support his delusions. His decision to adopt Marek as his son is because "it's the most dramatically interesting thing to do". He has "an incredible ability to see a game in everything" so he's "not quite contending with the truth".

With regards to the drought and famine that strike Lapvona and the gross and disgusting things that happen as a result, Hill admits (though considers it a compliment) that she nearly vomited reading some of it. Terrible deed are committed and there's no real reckoning for those involved.

Moshfegh's response is that she doesn't blame the characters for their behaviour - "you can't politely be the one who survives in a situation like that".

Did Moshfegh have the ending in her head when she started the book?

She says she had it planned out in her head what would happen but she "doesn't know exactly how I'm going to write it - I really didn't know what was going to happen".

A questioner from the audience wants to know of the unanswered questions in her books - does she know the answers to them? Moshfegh says she doesn't. People often ask her what happens to Eileen after the book ends and she doesn't know, "what's on the page... is as much as I want to understand".

Hill asks her about the article she wrote for Granta, 'Jailbait', in which she describes her ambition as a teenager was not to be successful but "to use my writing to rise up to a higher realm of existence". Is that still true?

Moshfegh says that when she wrote the article she was making fun of the drama of that but actually "it's still totally true" and characterises it as "rebellious sincerity", something she thinks she's returning to - "...it's the 90s all over again".

How is it working with other people on film projects?

"REALLY interesting" says Moshfegh. Novels are such "solitary work" - "I do it completely alone in a quiet room". It's been really cool but really challenging and it's been a learning curve for her - "it's a whole other world... the movies".

And it's not all dark stuff, either "comedy is just a huge part of what I do, whether or not it's actually funny".

When Hill suggests that she sounds very casual and relaxed about all these projects she's working on Moshfegh replies "I'm not relaxed about it at all, don't worry".

And so the session ends, but by now it's 1am in Amsterdam, so I hope Ottessa Moshfegh can relax at least a little.

Further reading

- Books by Ottessa Moshfegh

WORD Christchurch Information

- Visit our page of WORD 2022 Festival coverage and info

- Visit the WORD Christchurch website

- Follow @wordchch on Twitter

- Like @wordchch on Facebook

- Follow @wordchch on Instagram

Add a comment to: WORD Christchurch 2022: Faith and The Faraway Near: Ottessa Moshfegh