It's nearing 5:30pm on Saturday night, and The Piano's foyer is teeming with people; a little community in and of itself, positively buzzing with anticipation for the evening's "Coercion, Cults and Control" talk. I'm one of these eager audience members - having read our three panellists' books in preparation for the event, I cannot wait to hear Anke Richter, Byron C. Clark and Lilia Tarawa take the stage to discuss all things cults, alt-right extremism, and disinformation traps.

After a warm welcome by WORD 2023's Executive Director Steph Walker, the event's speakers - informally referred to in the WORD office as the "culty panel" - are brought on stage to much applause. Host Guyon Espiner introduces our trio, who are here to chat about how high-control groups attract, trap, and otherwise destroy ordinary people.

The night kicks off with a question for Lilia Tarawa, the only panelist to have cult experience from the inside. Gloriavale Christian Community is an infamous, isolated religious group that resides on the West Coast. Lilia not only grew up there - her grandfather was Neville Cooper, founder and leader. Did Lilia see him as a cult leader, Guyon quizzes?

For Lilia, as a child who knew nothing other than what she was told, her grandfather (known to his followers as Hopeful Christian) was the highest form of authority, a man of God. People were drawn to him for his mana and power; he held a great amount of charisma, and was an articulate public speaker.

She goes on to tell an anecdote about a positive school report she received at age 6 commending her leadership qualities. This report was read out by Neville to Gloriavale's large communal hall. Expecting praise, Lilia was instead humiliated by her grandfather in front of hundreds of her peers. He ranted at length: Gloriavale does not want women who are "bossy", who might grow up to be something. We want meek, humble women who will do as they're told. It was a clear signal to herself and the other women in the community - know your place.

It's easy to see why Lilia, who speaks eloquently and earnestly, was recognised for her leadership abilities from a very young age. And though this aspect of herself was discouraged during her time in the community, it's in full bloom today - the audience are hanging on to her every word.

She reads a small passage from her book, Daughter of Gloriavale, about the extensive domestic duties of women in the community. This is especially relevant nowadays - the Employment Court recently ruled that six Gloriavale women were not volunteers but employees, working in extremely harsh conditions. When Lilia mentions the women's victory, the audience erupts into raucous applause. The case will undoubtedly set a precedent for future instances of modern slavery and exploitation.

The conversation then turns to Byron C. Clark, author of Fear: New Zealand's Hostile Underworld of Extremists. Guyon observes how the prevalence of the alt-right and conspiracy theorists in New Zealand exploded in March 2022, when protests were held outside New Zealand's Parliament buildings. This very event was the catalyst for Byron's book, which investigates how our country got to this point.

Byron shares how he witnessed the movement bubbling up throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. Behind every Facebook comment thread were real people. And these people were receiving and sharing disinformation at rapid speeds. Controversial or otherwise false material originating from overseas was viewed by Kiwis on YouTube or other sites, then cycled through Facebook groups. People would create petitions and discuss this information in talkback radio stations, sending the impression that certain issues were more mainstream than they really were. Small political parties jumped on the chance to comment, then larger parties. It's a fascinating example as to how disinformation campaigns end up in widespread politics and media. New Zealand's conspiracy groups are "fringe - but a lot of people".

Byron reads an excerpt from Fear, detailing the harassment and death threats government workers received during the protests. It recalls how, in the crowds outside Parliament, COVID deniers were developing oddly COVID-like symptoms - but were explaining them away as "electromagnetic field radiation" from technological devices. Byron's account of occupiers wearing tinfoil hats and hiding under safety blankets gets plenty of laughs, but despite the ridiculousness it's hard to forget that the 2022 protest was decidedly not peaceful.

Next, Anke Richter speaks of the chance encounter which led her to write Cult Trip. She first heard of Centrepoint from a survivor in 2012, and was stunned at how little known the cult was in the public domain. She sought to make the story heard, and delve into cult coercion tactics.

Centrepoint's leader, Bert Potter, had plenty to offer his followers, Anke explains. He knew experimental therapy, had learned from the Indian philosopher Osho; he brought with him perspectives that were perhaps more radical, but also freeing, in 80s New Zealand. Centrepoint highly emphasised "sexual healing" and free love. Was it a "sex cult", Guyon questions? Anke plainly states that it was a "sex abuse cult".

She recites a harrowing segment of Cult Trip, that details Centrepoint survivor Louise's suicide attempt at just 11 years old, after repeated, horrific abuse. Bert Potter claimed it was because she wasn't receiving enough love, and used the situation to try to take further advantage of Louise. One line of Anke's reading makes the audience fall deathly silent:

Louise was waiting for someone to notice... Trying to kill herself hadn't worked, but no one came to rescue her.

At this point in the panel, the conversation starts merging towards similarities each writer has picked up on in their experience and research. The following are some of the big topics of the night:

Who is susceptible to cults and disinformation campaigns?

In Anke's informed opinion, the only people that are unlikely to ever become swept into the magnetism of cults or conspiracy theories are charismatic narcissists - "because then you're more likely to become a cult leader". People who think they're immune are often more susceptible, since they cannot recognise when they've fallen into a cult trap. Cults also have an excellent way of tapping into that sense of community that we're all searching for.

Lilia, who grew up amongst an incredibly tight-knit community, highlights how the community provided everything. It was a haven for people who were lonely or struggling financially. The bonds between members were strengthened through isolation - everyone was in one little bubble, like one giant family, working towards one purpose. And that's the catch, Lilia says: "We like to feel like we're a part of something. We like to feel like we're belonging somewhere, that we're not alone. Cults very much provide that to people."

Even tonight, we're gathered together as a community over a shared interest, seeking connection with each other. "Wait, did I just join a cult?" Guyon jokes.

For the alt-right groups that Byron writes about, that desire for connection is also the bait that snares new members. Young men, who feel lonely and spend a lot of time online, find a sense of purpose amongst these 'revolutionary' groups. The same goes for the free-thinking networks that popped up left and right during the pandemic - being stuck at home and terrified by the virus was incredibly isolating. Finding other sceptics on social media was a way to feel linked to others.

Why is it so hard to break away once you've been sucked in?

By the time you realise you're in a cult, Anke says, you've already given up so much. You may have donated life savings, and therefore lost your financial freedom. You've likely cut off friends and family on the outside. The hardest part, however, is acknowledging the deceit and all the mistakes you've made. You'd have to reverse your entire way of thinking. Anke hopes to see a social service arise to protect people who have left cults - currently, assistance is carried out by volunteers.

In Gloriavale, there's no way to get outside information. Lilia describes the scarce, heavily edited news they'd receive, and the lack of televisions, phones, and internet. Members only knew what they were told by the leaders, and that was their source of truth. For absconding members, the outside world became overwhelming. Lilia herself was bombarded with information when she left - there were so many different religions, news sources, opinions, experts on topics - all she could say was "What? There's not only this one way I was taught - there are hundreds and hundreds?" It was hard for her to figure out what to do with her life. She now needed money to live, when everything had previously been provided for her. Though it was terrifying, Lilia says that her greatest gratitude today is "just that I have a choice; just that I can choose who I want to be."

Byron used to think that if people simply got the right information, they'd be able to remove themselves from disinformation campaigns or culty groups. Now, he can see that this just isn't the case. People "trust information based on the relationship that they have with the person giving them that information." If you have a family member or friend who has "fallen down the rabbit hole", there's no easy way to get them out, but the best thing you can do is be there for them - they're far more likely to listen to you than a stranger. That's why cults and extremist groups are so focused on cutting off outside support.

How can these groups attract members whilst hiding their damaging side?

Lilia recalls that Gloriavale members were encouraged to paint a "pretty picture" of the community to the outside world. But they were happy to do it - years of systematic brainwashing left them fully confident in the goodness of Gloriavale. Documentaries and community concerts were some of the methods used to create a positive public image.

Members of cults often put up a positive front. Anke notes, "Some of the nicest people I met - the most accommodating [at first]... were enablers, or in some cases perpetrators." Such people were charming, and would downplay what went on inside Centrepoint, or in other cases claim they had no idea what bad things were happening.

People aren't usually amongst the extreme stuff until they're already well on the inside. Byron disapproves of business models like YouTube - sites that exist to serve advertisers. YouTube's algorithm recommends further videos to keep its customers watching, which in turn can draw people into progressively extreme content at rapid speeds. It can happen so quickly that people are unaware of how blatantly untrue the information they are receiving is.

Before the event wraps up, the floor is opened to audience questions. Of particular interest is the use of the word "cult" - should we be using the term freely? Expanding its definition? Using different words for different groups? Anke uses the word a great deal in her work. It's a controversial term; if it's too clearly defined, cults can distance themselves from it by saying they don't check every box. She offers high-control groups as an alternative, since not all "culty" groups are religious. Lilia says she changes her terminology depending on the people she's talking with. Whilst she believes Gloriavale is a cult, not all ex-members do.

An audience member expands on this idea of terminology, asking how culty jargon works to create an "us-vs-them" mentality. Byron sees a lot of new vocabulary being floated around conspiracy groups in his research. It makes people feel like they have "special inside knowledge" of secret truths. Anke recommends the book Cultish by Amanda Montell, which explores how language is used in cult-like groups to entrap people. It's a tell-tale sign someone has been sucked in once they start using strange new words.

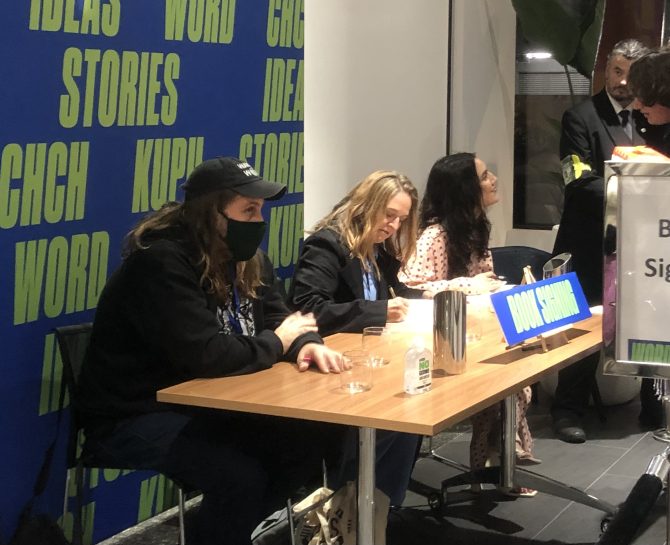

It has been a wonderful, informative night with our three panellists and host. I'm sad to see it end so quickly - I could have listened to their articulate, well-considered perspectives all night - but alas, the hour has flown by. After lengthy applause, the night ends with a book signing by all three authors. I'm incredibly grateful to have been able to attend this event and hear the voices behind the pages in person. I walk away with a greater knowledge of cults, extremist groups and disinformation campaigns, and an intention to be further understanding when I encounter such things in my own life.

Find out more

- WORD Christchurch website and 2023 programme

- Follow @WORDChCh on Twitter

- Follow WORDchch on Instagram

- Like WORD Christchurch on Facebook

- Our WORD Christchurch 2023 page

Add a comment to: WORD Christchurch 2023: Coercion, Cults and Control