“We must remember to remember” Tā | Sir Tipene O’Regan

Described as “a treasure house for future generations” by Helen Brown, Senior Researcher Ngāi Tahu Archives, Kareao is the Ngāi Tahu online archival database. Launched at the tribal 2019 Hui-a-Tau | Annual Meeting, it currently holds over 4000 records made up of photographs, manuscripts, maps, taonga, biographies, oral histories, and audio-visual material.

I have to say I was somewhat intrigued when I saw this session advertised. Having visited the Ngāi Tahu Archives myself, I was interested to find out the stories behind some of the taonga held within the collection from the people charged with their care. So as instructed, I followed the path of the Kareao to the Concert Hall at the Piano for what was to be not only an interesting but very entertaining presentation.

Hosted by the 2022 WORD Programme Director, Nic Low, the evening was woven together in a lecture style of both scholarly and personal insightful reflections. The panel consisting of members of both the Ngai Tahu Archive team and Te Pae Kōrako | Ngāi Tahu Archive Advisory Committee took turns talking back into life their chosen taonga | treasure. Following a mihi | welcome from Te Pae Kōrako Chair, Tā | Sir Tipene O’Regan, Low introduced the nights proceedings and of course the panel before “opening the archives and inviting them to talk.”

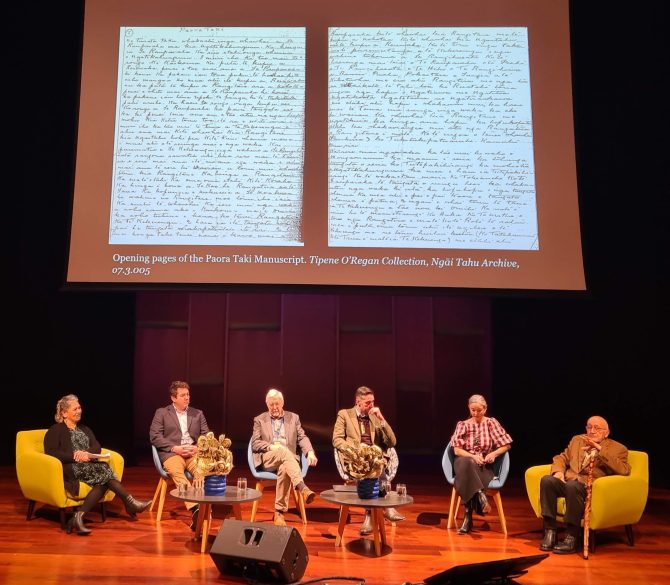

Tā | Sir Tipene O’Regan was naturally the first of the panel to give his presentation. A very learned man, O’Regan chose to discuss the Paora Taki manuscript. Taki, a survivor of tribal internal and external battles during the 1820s to the late 1830s dictated a detailed account of the Ngāti Toa battles in his later years. Transcribed by Molly Tikao (daughter of Teone Taare Tikao) at Rāpaki, the text was held by the Tikao whānau until it was gifted to the Ngāi Tahu Archives in 1980 by Raukura “Fan” Gillies (nee Tikao) youngest daughter of Teone and her son Wiremu Gillies.

Perhaps the most significant things for O’Regan are not only the “remarkable… wealth of detail it contains, [but Taki's ability to recall] not only the actions but the names of both Ngāi Tahu and Ngāti Toa who were involved in those battles.” As O’Regan talks, you can see and feel the respect he has not only for this manuscript but also for Taki himself. Two battle weary gentlemen reflecting on their youth spent fighting for their people. You can’t help but admire them for their generosity of heart. As O’Regan reminisces on times gone by, he recalls with affection the work the late Te Aue Davis undertook with Anake Goodall in translating the manuscript which is now available on Kareao. This manuscript is beyond doubt a treasure for future scholars but more importantly future Kāi Tahu whānui | tribal members.

Staying with Paora Taki, the next presenter, Helen Brown, spoke of a tiki whakairo | carving that was gifted by Taki to Captain James Drysdale on February 9, 1883, and then to the British Museum. Although paperwork accompanying the taonga is very detailed, Brown notes the letter from Taki was misrecorded not only wrongly recording Rāpaki as Rapahi but Ngāi Tahu as Ngatihou. This mistranslation has led to the taonga being wrongly given providence to Ngāti Hau of Whanganui. While Ngāi Tahu Archives are currently working with the British Museum to rectify this, Brown notes the significance of the taonga to Te Hapū o Ngāti Wheke of Rāpaki. While excited that the taonga has been rediscovered and digitally repatriated, they like Brown are hopeful a conversation of full repatriation may be held in the not-too-distant future.

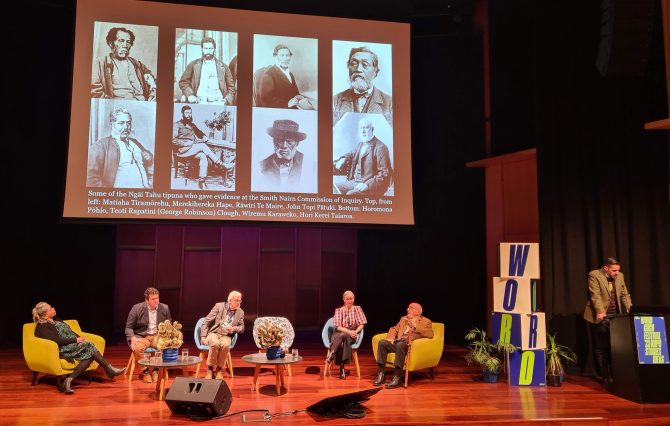

I was pleased to see Dr Michael Stevens, Te Pae Kōrako member, took time out of his chronicling of “the World History of Bluff” to highlight the causative connection between loss of Māori land and Māori poverty as documented in the Smith Nairn Commission papers. I have always found Stevens to be an old soul in a young body, with wisdom and insight beyond his years, not to mention a wicked sense of humour. Stevens didn’t let me down. Scholarly yet clear, with a dash of quirky [whānau] humour [IYKYK] Stevens provided a personal perspective through the words of his tipuna captured in these documents.

The 1879 Middle Island Native Purchases Royal Commission of Inquiry (Smith Nairn Commission) was a “royal commission established to investigate grievances associated with the Kemps, Akaroa’s, Otago and Murihiku Purchases.”[1] Highlighting the evidence from tipuna | ancestors such as Matiaha Tiramōrehu, Stevens outlines how compelling such primary sources are, with their recount of events and eyewitness reports of the impact such things had on Ngāi Tahu. Summarising the information contained in these documents, Stevens states that as a result of these sales Ngāi Tahu were “herded on to reserves, [and thus] it was conquest by contract.” There was “no positive outcome, no remedial action of the broken promises, [in short] these documents are a profound record of a fraudulence neglect by the Government of the time.” As he speaks the passion and sincerity of his tipuna can be heard, calling to mind the Kāi Tahu whakatauki ‘mō tātou, ā, mō kā uri ā muri ake nei – for us and our children after us’ and ‘he mahi kai hoaka, he mahi kāitakata – as the sandstone consumes the pounamu, so to Te Kerēme consumed our people.’ Four generations of Kāi Tahu fought Te Kerēme | Ngāi Tahu claim with the Government. Each generation passing the baton to the next until the spring of 1998 when “the taniwha went to sleep”[2] with the passing of the Ngāi Tahu Settlement Act. Nearly 25 years on from settlement it is obvious that the aspirations of previous generations are now coming to fruition.

Mahika kai | natural resources were the backbone of Te Kerēme and still remain an important part of Kāi Tahu life. It was fitting then that the next two taonga are centred on mahika kai. The first, introduced by Pae Kōrako member Professor Atholl Anderson, was compiled by H.K Taiaroa in 1880. Identifying names of numerous sites of nohoka | seasonal settlements, wakawaka | gathering areas and kaika | settlements throughout the Waitaha | Canterbury region, it provides a valuable record of occupation and use. This was no more important than during the years of Te Kerēme where the government required Kāi Tahu to provide such proof.

As an archaeologist, Anderson has utilised such taonga in his work. He comprehends the valuable role that they play in understanding the life and times of his tipuna | ancestors. Used with the Ngāi Tahu seasonal calendar compiled by H. Beattie and later revised by Dr R. T. Tau, Anderson spoke how he was able to ascertain not only the seasonal use of those sites but also, the type of food group gathered from which area – protein from Waitaha and carbohydrates from Otago. Anderson then drew our attention to a discovery of artifacts found in a cave shelter named on the Taiaroa Map. Left prepared, ready for use when their owner/s returned, Anderson views them as “furnishings on the landscape.” For him it demonstrates the view of his tipuna that “the landscape was [a collection of] many rooms. The perceived security of ownership, meant the owner/s felt secure enough to leave them as found.” Furthermore, Anderson notes that all the items were prepared for use – huruhuru Kākā | Kākā feathers, Tīkumu | Mountain Daisy, awe Kōtuku | White Heron plumes and Kōkōwai | red ochre which all denote mana | status. As an archaeologist this is an important point to note as Pākehā maps of that time trivialised such places as just a fishing camp. It is not until you take the time to examine all records is the truth revealed.

Similarly, an 1898 map compiled by Rawiri Te Maire demonstrates the close relationship Ngāi Tahu had with their landscape. As the slides changed, we were taken on a further journey of exploration as Takerei Norton, Ngāi Tahu Archives Manager, outlines the intricate detail of not only the rivers but all their tributaries depicted in this map. Given the map was produced from memory at a time before modern technology, it is quite an accomplishment and Norton is right to be suitably proud. Norton has managed the Archives since 2012 when they moved under Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu. He knows these records well, treating them with affection and reverence, this map is but an example of this esteem he holds these taonga.

The last of the panel to present was Pae Kōrako member, Puamiria Parata-Goodall. A self-confessed kapa haka | Māori performance arts freak who loathes public speaking, she naturally sung her way through her presentation on the tribal waiata | song strategy Te Hā o Tahupōtiki. “A series of tapes and CDs produced from a desire to strengthen and develop Kāi Tahu culture and identity through waiata and haka.” Parata-Goodall recalls the first being produced and circulated to tribal members throughout the country as the tribe was preparing for the third reading of the Ngāi Tahu Settlement Act in the late 90s. While she acknowledges the guidance of senior kaumatua Mrs Reihana Parata and the late Mrs Ruahine Crofts, she neglects to mention that she and a small group of cousins spent months on the road travelling to various marae to hold practices for tribal members. This was quite a feat given the distances travelled, the diverse make up of participants – for some this was their first tribal contact.

As Parata-Goodall sings Nā tō a tribal chant recalling the origins of the world, the memories of those practices start to fill the room. She speaks of how the original series of three were deliberate in the waiata that they represent. Blue – a state of becoming, important waiata composed and sung by those who were part of fighting for Te Kerēme. Red – a state of being, the transition point from grievance to settlement. Gold – the new dawn, new beginnings, new hope as Kāi Tahu reclaim their identity. A fourth of the series, Ka Koriki te Manu, a compilation of old and specially composed waiata was produced in 2015 in preparation for the pōhiri to welcome Te Matatini – He Ngākau Aroha 2015 to Ōtautahi | Christchurch. While she played it down in her presentation, again Parata-Goodall played a key role in preparing not only tribal members but the rōpū kapahaka | kapahaka groups for the pōhiri.

While the strategy itself is noteworthy, it is actually the content of the waiata that are the true taonga. Recalling whakapapa | genealogy, deeds and events of tipuna, this is a process Māori have used to intergenerationally transmit information. Simple in nature, yet they hold the depth of knowledge only found in manuscripts. Parata-Goodall lyrically weaves her way through her presentation, being joined by those that remember the words. It is therefore fitting that she concludes her presentation with the Kāi Tahu anthem Tahupōtiki written by the late Ruahine Crofts, that was sung in Parliament following the passing of the third reading of the Ngāi Tahu Claims Settlement Act. Perhaps it’s because we have spent the evening talking the archives back to life, remembering to remember, or we are now approaching the 25th anniversary of the passing of that Act, I am transported back to that moment, as tribal members join Parata-Goodall in song.

Kareao is an amazing database resource that is available for all to use. Named after the supplejack “that meanders its way through the lowland forests of Te Waipounamu… [this database] leads from one point to another, linking, connecting, and ultimately taking explorers in a myriad of directions of discovery.’[3] Kareao was born of the desire to have a single point of entry to Ngāi Tahu history and this has been achieved. While Kareao has successfully begun digitally repatriating mātauranga Ngāi Tahu held in other repositories throughout Aotearoa | New Zealand and the world the hope is that one day these taonga will physically be part of the Ngāi Tahu Archive.

As I head off into the chilly night, I am reminded of a waiata written by Hana O’Regan after settlement commemorating those who worked tirelessly on Te Kerēme for nearly 150 years.

Mā wai e hua nei te haumāuiui o te tini, inā kurehu ake te tōtā i te rae ki tua o mahara e?

Tītia ki te uma kā wai o ōhākī kia rere kā wai o mihi e ki roto i ō uri ā haere ake neiWho will speak of the accomplishments of the many when the sweat on the brow dims to but a distant memory?

Hold fast to your heart the memory of their last words so the waters of praise will flow within your descendants forevermore.

With the work of the Ngāi Tahu Archive team and Te Pae Kōrako have ensured that the deeds of the many will be remembered by generations to come. I congratulate the Ngai Tahu Archive team and te Pae Kōrako past and present for the work they have done to date. I also acknowledge Tā Tipene O’Regan and those who had the great foresight to initiate the Ngāi Tahu Archives over 40 years ago. With the long-awaited change in the Aotearoa | New Zealand School Curriculum to include Aotearoa | New Zealand history, Kareao is a timely resource which will help us all to remember to remember.

[1] Te Whakataunga o te Kerēme, Te Rūnanga o Ngai Tahu

[2] Tā Tipene O’Regan, Third Reading Ngāi Tahu Settlement Act, 28 September 1998

[3] A Treasure House for the Future, Issue 84, Te Karaka

Photos

Find out more

- WORD Christchurch website and 2023 programme

- Follow @WORDChCh on Twitter

- Follow WORDchch on Instagram

- Like WORD Christchurch on Facebook

- Our WORD Christchurch 2023 page

- Photos from WORD Christchurch 2023

Add a comment to: WORD Christchurch 2023: Whaia te ara o te Kareao – Follow the path of the Kareao