This is not David Mitchell's first go round at WORD Christchurch, he visited in person in 2015, was supposed to appear virtually at last year's festival, and is finally, in 2022 in conversation with former WORD programme director, Rachael King, who despite having passed over directorial responsibilities is still keeping a foot in the WORD water as a writer (and presumably, a fan).

Tautoru / TSB Space at Tūranga is bedecked in a combination of ballons, flowers, disco balls and tinsel. It's like a mad carnival/disco and each place at each table has a vinyl LP as a placemat.

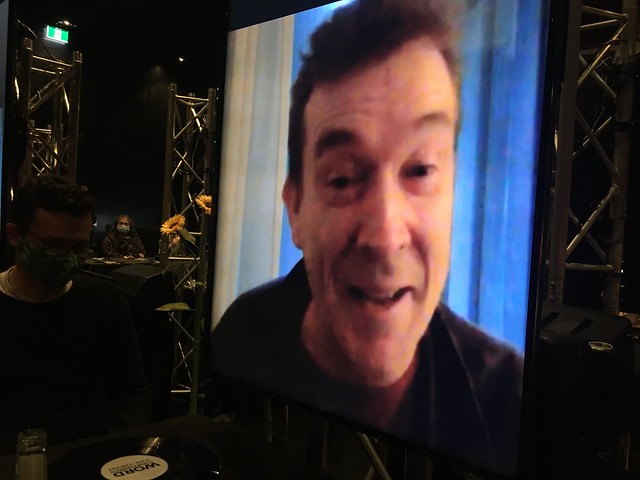

And suddenly the formerly black screen at the end of the table comes to life and David Mitchell is there beaming in from a hotel room in Holborn, London. For us it's a little after 6pm. For him it's around 7 in the morning and later I will find myself wondering how anyone manages to be this affable and enthusiastic about talking to other humans this early in the morning. But I've come to the conclusion that David Mitchell is just the sort of person who is interested in things and people and as a consequence likes to talking about things to people whenever he has the opportunity. He also took occasional swigs from what I assume was a mug of tea so I'm sure that helps too.

Rachael King let's us know early on that the questions she'll be asking are not of your typical literary festival type. Instead, between interviewer and interviewee they've come up with a list of queries that are more in keeping with an "idiosyncratic TV quiz show". This is a novel approach and one that means the subject matter goes all over the shop but still somehow comes back to writing, and creativity for a lot of the time.

Mitchell is not entirely at ease with the notion that there are "multiple versions of me" on the big screens at each table, "so I'll try and not think of it".

He's currently in London working on a TV series which is being put together with autistic actors, writers and talent and describes it as "... a flying machine that we're building in mid-air". Yes, David Mitchell does a good metaphor.

King starts of with a question about how the pandemic has affected things for him and it's a mixture of being pleased about how people can be creative in their solutions with regards to festival events like the one that we're at, muddled up in terms of time during these "pandemic years", and the fact that "... nowhere has enough stuff" due to supply chain issues, the war in Ukraine and such. "Never a dull moment, eh?"

Then we move on to screenwriting. How, King wonders, do you translate prose to film language?

"You don't so much translate it as leave it at the door," he says. When it comes to, for example, describing a storm in literature you have to "tip toe your way through the minefield of cliché" and try and not make your version of a storm sound like the same one other writers have described, to try and create a new metaphor. Whereas with screenwriting all you have do is:

"EXT: Christchurch. A storm. Night"

And then it's someone else's job to make the storm look how it should.

And you should "only resort to dialogue when there's no other way".

Which does explain why a lot of spoken exposition in films or television shows feels so clunky. It's the medium of showing not telling, I suppose.

When he first started out doing screenwriting he says he had a tendency to overwrite. "Gravity towards economy," he says "is the biggest thing".

From there King asks the first of the "quiz-type" questions. What's in your compost heap? Which is a another way of asking about his influences.

Mitchell mentions an early 70s television show called Mr Ben in which a character puts on costumes in a magic shop and then enters the world of the costume and goes on adventures as well as Doctor Who that had a similar appeal of going into a blue box and exploring a different world but also the fact that The Doctor "wins by talking and problem solving and being kind."

He also throws in the maps at the end of The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit, though not the narratives themselves - J. R. R. Tolkien would never win any awards for style (harsh but fair). He admires the world-building and the abundance of care required to make everything in that world real.

Ursula Le Guin and Rush, who he idolised, are also mentioned. He loves that Rush "made high register vocabulary cool" and that their concept albums were stories, narratives. "Narrative is not a thing that the page has a monopoly on."

Next question. What's your theme song?

At this point Mitchell agonises over the question chastising himself for not having a good answer, to which King replies drily, "it was your question". But it's still only 7.30am where he is. He's already more articulate than most of us. He lands on some music, not exactly a song, namely The Lark Ascending by Vaughan Williams to murmurs of approval from people in the audience far more knowledgeable than me, it turns out.

"I love the contrasts in it and it's so beautiful"

Then Mitchell turns the question around and puts King on the spot who chooses "Old as the hills" by Tiny Ruins which is canny because then it gives her the excuse to ask about his collaboration with Hollie Fullbrook in a session on later that evening in which he will read several short stories inspired by Fullbrook's music and Fullbrook will play music inspired by his stories.

How does it work, weaving a song into a story?

Mitchell imagines that the songs are a person. They are mostly first person songs, so "they're halfway to being a story already". Her verses are "snapshots", like polaroid photos, "so I put those in order like key scenes in a story". He calls Fullbrook's music "mood-drenched". In a quite surprising metaphor that involves cask wine he describes opening up the plastic tap at the bottom of "the box of mood" and letting it "spill on the narrative". I did say he does a good line in metaphors.

Did he learn anything new or surprising in his research for novel, Utopia Avenue?

Yes. That "bass players never call themselves 'bassists' always 'bass players'" he says. To Rachael King. The former bass player. From there it moves to some discussion of the nature of rock bands and how they're more than the sum of their parts. There were 4 individual people who made up the Beatles, for instance, but The Beatles itself is a distinct fifth thing - an "independent organism".

Does Dean (from Utopia Avenue) write his songs on the bass?

It's not discussed in the book but Mitchell thinks he probably writes them on an acoustic guitar "but the bass lines would never be too far away from it'. Bass players in general, he thinks, are underrated and "no band can be a great band without a great bass player".

Next question. Creativity - what is it?

His answer to this ranges far and wide but what it boils down to is this:

"We think of artists as people in society with a monopoly on creativity and it's not true."

Nurses, farmers, scientists, parents with small children, people with disabilities - all of them are having to invent strategies and problem solve every day and he's suspicious of

"...artists who mystify what we do."

Here's to all the non-artists who use creativity in their everyday lives... it does not belong to the tribe of the arts."

Fair enough. If his brain was a house what would be in its rooms?

"The bodies!"

But also, "organised chaos, a big mix of furnishings... Japan... I hope love in it's different permutations - the misery and the joy of supporting Liverpool all your life, the agony and the ecstasy!" He'd also expect some weird Being John Malkovich-esque gathering of all the versions of himself. A medieval cellar. A winding stair.

Again he turns the question back on the questioner and so King's brain house would have moth-eaten taxidermy, and orchestra tuning up, and "all the books I'll never write".

Has he ever encountered a ghost?

He thinks so, when he was living in Japan and woke to find he couldn't move and that there was a person standing at the end of his bed asking why he was in their house. So he tried to explain in his best beginner japanese who he was and why he was there and they faded away and then he could move again. The house he was renting was near a river where many people had died following the bombing of Hiroshima so it was already a spooky place.

What's something that not a lot of people know about him?

Mitchell confesses that during lockdown he read an article about how not to waste time during lockdown that recommended not spending too much time on social media but instead to go to an online chess website and play a short game of chess instead against another person. "I just got ADDICTED to this" and to this day he has to try and limit himself to an hour at a time.

King then asks him about a very particular form of synesthesia that he has.

Apparently Mitchell gets a strong colour vibe from men's names of his generation, "if your name is from the same 'name bank' as mine - biblical, whitish names" then he can tell you what colour that evoke for him and he rattles off a few; Nicholas = yellow, Richard = red, Neil = brown, Chris = golden, Steven = green. Women's names don't seem to have the same effect, "I get a bit vague with women..." to murmurs of amusement from the audience.

"It's not much of a super power is it? I don't think The Avengers would have me..."

King prompts him to consider if his synesthesia truly is limited to this because doesn't he have some strong feelings about the shape of words and sentences?

He does believe that there are ugly and beautiful sentences based on the way it looks - the rises and falls of the letters. And its structure can be beautiful, "short, sharp sentences about short, sharp things can have a short, sharp beauty". The beauty doesn't come from what the sentence is about but how it harmonises with what it's about.

Audience questions begin and the camera and microphone move around the space so that Mitchell can see who is asking the question. The first wants him to choose between Neil Young and Crazy Horse or Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young. To which he says he simply cannot choose. Sometimes you want those "airtight harmonies" from 1969-1970 and sometimes you want "the galloping thunder... the voice like a barn falling to pieces".

Another questioner wonders which Doctor Who and where in space and time?

His favourite is Peter Capaldi, though David Tennant was fun too. His favourite episode was "Heaven sent" where almost the entire episode is just the one character as played by Capaldi. And he'd like to go to the Cat planet that's populated by human cats, though he's allergic so he'd have to take some antihistamines.

If you had a spirit animal, what would it be?

This is a somewhat problematic question because the concept of the spirit animal is based on real indigenous beliefs but has been appropriated and treated like something that's a fun parlour game.

But no one else seems to mind and Mitchell answers to the best of his ability saying that in the past he's liked the idea of being a sea otter because he feels a kinship with the sea and they just "hang out all day and have lots of sex..." but it turns out they're "vicious sons of b*tches" who do cannabilism and various other nasty things. So he'd probably have a skylark instead.

When asked about the book he's written as part of the Future library project (in which books are locked away and not published (or read) until 2114), he says that he did actually write it - it's not just blank pages and that he can't tell us anything about it because he'd have to "track you down and silence you". It sounds like he did it as a sort of hopeful downpayment on the future. Things seem sort of bad and there's not a lot that he specifically can do about the state of the world but "this was an opportunity to cast a vote in the future... a vote of faith in the future".

"Maybe this is just a drop in the ocean but what is any ocean but a multitude of drops?"

King wraps up by rattling off the remaining "quiz" questions that we haven't got time for and they are tantalising:

- Is there a place in the world that you think is a liminal place?

- Which question have you been asked a million times at literary festivals and you just hate?

- What would be your specialist topic on Mastermind

- What's an unanswered prayer that you've made that you were eventually glad went unanswered?

And finally one last one that there is time to answer: what's your favourite word, tree and an island?

Word: Pavonine meaning relating to peacocks (in the same way that feline relates to cats, canine to dogs etc.)

Tree: One of the very old cedars in Japan that are 1000 years old

Island: The Chathams. He visited in 2000 and "a part of me is still there".

And then shortly afterwards, the screen goes to black and David Mitchell is gone again, into the ether. Or maybe the Chathams.

Further reading

- Books by David Mitchell

WORD Christchurch Information

- More photos from WORD Christchurch 2022

- Visit our page of WORD 2022 Festival coverage and info

- Visit the WORD Christchurch website

- Follow @wordchch on Twitter

- Like @wordchch on Facebook

- Follow @wordchch on Instagram

Add a comment to: WORD Christchurch 2022: David Mitchell answers quiz questions