Richard William Pearse 1877-1953

Richard Pearse was a South Canterbury inventor, engineer and farmer. He is famous for being one of the first people on earth to leave the ground in a powered aircraft. His life and work have inspired books (including a novel), poetry, stamps, documentaries, and three stage plays.

Richard Pearse was a South Canterbury inventor, engineer and farmer. He is famous for being one of the first people on earth to leave the ground in a powered aircraft. His life and work have inspired books (including a novel), poetry, stamps, documentaries, and three stage plays.

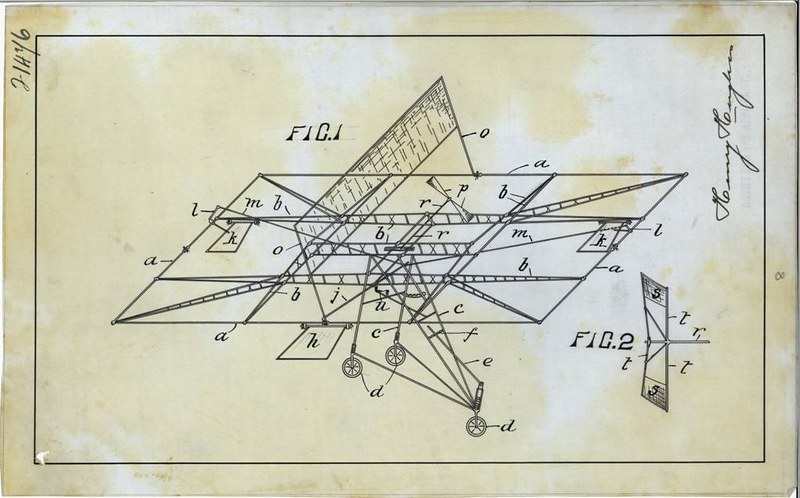

His first plane, built at Waitohi, inland from Temuka, had many innovations - a steerable tricycle undercarriage, wing controls, and a variable pitch airscrew made of metal, not wood. The propeller was directly connected to the crankshaft of the engine. The power-to-weight ratio of the plane was better than many aircraft designed in later years.

Fact file

Born: 3 December 1877 in Waitohi, near Temuka

Died: 29 July 1953, in Christchurch

Early life

Richard Pearse’s parents were Digory Sargent Pearse and Sarah Browne. They had nine children, including Richard who was the fourth child.

All of the family were good at tennis, chess and music and together they formed a family orchestra. Richard played the cello. Richard also played golf.

Richard’s parents farmed a large property at Waitohi, then a rugged and isolated part of South Canterbury. Waitohi is inland from Temuka, just north of Timaru.

Richard was quiet and independent at school, but a keen reader who would day-dream in class sometimes.

When he was sixteen Richard left school to work on the family farm, but he did not like farming. He wanted to go to university and study engineering but his father could not afford to send him.

Richard was given a 100-acre block of land when he turned 21, but instead of farming, he built a workshop with a forge and a lathe, and began building his own inventions.

Adult life

Richard Pearse’s first invention to receive a patent was a type of bicycle, where the pedals were pushed up and down, rather than around, and the tyres could be pumped up while still riding. The bicycle frame was made of bamboo. But his real interest lay in flying.

Pearse began working on ideas for powered flight in the last years of the nineteenth century. He kept in touch with what was happening in the world of flight by reading the magazine Scientific American.

By 1902 Pearse had probably built his first lightweight two-cylinder engine. He then built his first plane out of bamboo, tubular steel, wire and canvas, and would practise taxiing it around his paddocks.

Pearse made his first public attempt at flight along the Main Waitohi Road, and after staying in the air for about 50 metres, crashed into a gorse fence. (Pearse was not very good at farming and his gorse fences were about 3 metres high).

There is no official record of this attempt at flight though eye witness accounts suggest that it took place on 31 March 1903 (or even possibly 1902). Supporting evidence in the intervening years has sometimes contradicted these dates.

What Pearse achieved was a powered takeoff, not controlled and sustained flight. His was the fifth successful powered takeoff to have taken place anywhere in the world.

Pearse did not believe he flew properly, leaving that to the Wright brothers, Wilbur and Orville, who flew on 17 December 1903 at Kittyhawk in the United States.

A number of eyewitness accounts tell of seeing his plane leaving the ground on several different occasions, but it is not certain if any of them could be described as true flight, that is, flying under control for a reasonable length of time.

A solitary life

During his life Pearse was a solitary character - he took few notes and talked to few people about his work. He was regarded as intelligent but eccentric, earning him the nicknames ‘Mad Pearse’ and ‘Bamboo Dick’. It was not until after his death that the importance of his work became more widely appreciated, thanks to the efforts of George Bolt, the founder of the Canterbury Aero Club.

While he is most remembered for his work with aircraft, Pearse built all kinds of machinery, which according to South Canterbury Aviation Heritage Centre included:

a needle threader, power cycle, recording machine, magic viewer, harp, power generator, potato planter, topdresser, motorised discing machine and two sorts of musical box.

Pearse kept to himself. He never married. In 1911 after becoming very ill with typhoid, Pearse moved to a farm near Milton in South Otago where he carried on inventing, designing and making several pieces of farm equipment. He was conscripted into the army in May 1917 and was sent overseas in January 1918, but fell ill and returned to New Zealand later that year.

Pearse’s work was mostly undertaken alone, without formal training. He was constantly improvising from materials he found or recycled. Playwright Mervyn Thompson wrote in the preface to Jean and Richard: A fantasy:

Pearse struggled alone, invented alone, flew alone and died alone. Instead of the cheers and fame he deserved he remained obscure and unsung, known to few — and then mainly as a mad man!

Bungalows and Pearse’s ‘second home’

Pearse lived in Christchurch from the 1920s. In November 1921, he paid £45 for a quarter-acre section on the south side of Breezes Road. Originally it was number 4 Breezes Road, but is now 164. Pearse built the three-bedroomed bungalow entirely by himself.

In 1921 he began designing what he called his ‘Utility Plane’. The patent for this was granted in 1949. The Utility Plane had a tilting engine to allow for vertical take-off and landing, and Pearse hoped it would one day become a plane which everyone could afford and fly, taking off from a backyard anywhere.

Unable to attract interest from aircraft companies to further develop his Utility Plane, Richard Pearse became obsessed with the idea that people were trying to steal his inventions.

Two years later he purchased more land at 68 Wildberry Street and built a second bungalow. The building fee of 30 shillings allowed him to construct a house to the value of £500. A third house, on the corner of Wildberry and Dampier streets followed. It was finished in mid-1928. Pearse rented the properties to tenants and lived off the income.

Research for Pearse’s projects was often conducted at the library. In the fourth edition of The Riddle of Richard Pearse, Gordon Ogilvie writes (page 146):

The Christchurch Public Library now became almost his second home. He spent a great amount of time in the reading room poring over tome after tome on engineering, aviation, mechanics, aeronautics and science.

The ‘utility plane’

Debate around whether Pearse was the first to fly is what springs to mind for most people about Pearse, but another of his lasting legacies was the last plane he built. At 68 Wildberry Street, he was able to work in his garage virtually full-time on his idea of a craft that would do for planes what Henry Ford did for cars.

Called the utility plane, Pearse’s idea was a plane that could land anywhere, and could also be driven like a car. The propeller was able to be moved from the front of the plane to above it by means of levers, providing the ability for vertical take-off. The plane was built in Pearse’s garage and is now housed, along with a replica of Pearse’s first plane, at Auckland’s Museum of Transport and Technology.

Pearse was admitted to Sunnyside Mental Hospital in Christchurch in June 1951. He died there on 29 July 1953 after a heart attack. He was 75 years old.

Recognition after death

Richard Pearse’s early achievements were almost forgotten until after his death when his last plane was retrieved from his garage and put into storage. It was going to be dumped, but was saved by an auctioneer’s decision to offer it to the Canterbury Aero Club.

After some years it was rediscovered by George Bolt, a former aviation engineer who bought the aircraft for the Museum of Transport and Technology (MOTAT) in Auckland. Bolt began to look more closely into Richard Pearse’s life and eventually a few remains of Pearse’s inventions, including the engine and propeller from his first plane and a home-made motor-cycle were found.

A replica of his first aeroplane was built and tests proved it would have been able to fly. It is on display at MOTAT in Auckland.

- A memorial to Richard Pearse was unveiled on 31 March 1979 at Waitohi.

Waitohi memorial, photo by Stella Linton. - In 1974 the ten-story Wellington head office of the Ministry of Transport land transport division was named Pearse House.

- Several documentaries have been made: Pearse (1975) written by Roger Simpson and with Martin Sanderson as Pearse; and Plane for the Million (1986), produced by Michael McNicholas and written by Ken Catran.

- A 2012 documentary Will it Fly? follows Ivan Mudrovcich, retired automotive engineer, as he attempts to rebuild Pearse's aircraft and to fly it.

- Pearse’s achievements also appeared in Peter Jackson’s 1995 mockumentary piece Forgotten Silver.

- In August 1981 a replica of Pearse’s first plane went on tour to America.

- In May 1982, the Timaru airport became known as Richard Pearse Airport.

- Solo flight a series of poems by Bill Sewell was published in 1982

- In 1990 an 80 cent stamp - intended for fast-post and air mail use - was issued by New Zealand Post as part of a series celebrating New Zealand innovators and trailblazers. Pearse's craft was also included in a 1999 stamp issue. In 2009, Richard Pearse souvenirs were created as part of the Timaru Philatelic Society celebrations for Timaru’s sesquicentenary.

Three plays have been written about Pearse: The first, Pearse, was written by John Leask and was first staged in June 1981 by the South Canterbury Drama League. A second, Jean and Richard: a Fantasy was written by Mervyn Thompson and produced by the Court Theatre. It was published in 1992. In Thompson’s play Jean Batten and Richard Pearse meet. A third production, Pearse, the Pain and the passion, was staged in Christchurch in 2003. It was written by Sherry Ede and produced by Penny Giddens.

Much research has been done over the years to establish whether Pearse’s planes could ever have flown. In an article, Geoffrey Rodliffe details the research attempts to verify if Richard Pearse flew and to trace eyewitnesses.

A newspaper report from 1909 uncovered by aviation author Errol Martyn suggests Pearse did not fly until long after the Wright Brothers.

Summary

Richard Pearse was an inventor of great ingenuity and imagination. His first plane looks very like a modern microlight in appearance. As well as his planes, he designed and built a number of inventions including a needle threader, a power cycle, a potato planter and a power generator. He did this without a formal engineering education and very limited resources. Almost everything he made was put together out of junked or recycled materials – old farm machinery, bits of wire, tin and metal tubing.

One difficulty with Richard Pearse’s work was that, unlike the Wright brothers, he did not keep records of his planning and building process or of his attempts at flight. His patent applications are the only written record of his work.

His achievements have been lost sight of in the debate over whether he flew before the Wright brothers carried out their witnessed and officially recorded flight. He worked on his own, in secret, and avoided publicity, so that nothing was known of his work outside a very small group of locals who observed some of his attempts at flying. Unfortunately, despite the ingenuity of the design of his first plane, Pearse’s work remained unknown and had no impact on the development of powered flight.

However it can be stated that Richard Pearse was the first New Zealander, and among the first people in the world, to make a powered take-off in a heavier-than-air machine which he had designed and built himself.

More about Richard Pearse

- Richard Pearse titles in the library catalogue

- Ogilvie, Gordon. The riddle of Richard Pearse: the story of New Zealand’s pioneer aviator and inventor

- Rodliffe, C. Geoffrey. Wings over Waitohi : the story of Richard Pearse

- Find articles about Richard Pearse in Christchurch City Libraries’ Papers database

- Andrew, Kelly. Talks to mark anniversary of Pearse’s birth, The Press, p. A; 7 December 3 2002.

Use at a library or enter your library card & password / PIN. - Our pages about inventors and inventions.

Online resources

- Ogilvie, Gordon. Pearse, Richard William 1877-1953, Dictionary of New Zealand Biography

- Cartoon by Murray Webb from Te Ara - shows Pearse ploughing while reading a book on how birds fly

- Richard William Pearse, Army Personnel Record from Archives New Zealand

- Richard Pearse Memorial IPENZ Engineers New Zealand

- Richard Pearse - inventor and aviator at NZ History.net.nz

- Man's first powered flight essay by Bill Sherwood

- Richard Pearse at Wikipedia

- Richard William Pearse (1877 - 1953) Aviation News and Resource Online Magazine

- Richard Pearse - First Man to ‘Fly’ a Mechanically Powered Aeroplane? by Chris J. Brady

- Bamboo Dick, first in flight, Debbi Gardiner at Salon.com

- Flights of fancy? BBC News Online Magazine

- First to fly mystery by David Killick

- Resources on Richard Pearse from DigitalNZ

- Pearse flew long after Wrights The Timaru Herald. A researcher finds a newspaper report from 1909 which he says proves Pearse did not fly until long after the Wright Brothers.

Historical newspaper articles

- News of the day Colonist, 9 November 1909

- Untitled Manawatu Standard, 10 November 1909

- A flying machine Clutha Leader, 30 November 1909

Online video

- Richard Pearse aircraft replica project part 1 and Richard Pearse aircraft replica project part 2

- Richard Pearse 1975 documentary, New Zealand On Screen

Eyewitness accounts

Podcasts

- Crosswinds Jack Perkins Retrospective, Radio New Zealand 2008

- Flight of Fancy Radio Spectrum Sunday, Radio New Zealand 2014