On Saturday 19 July 1919, the people of Christchurch awoke to a clear, frosty morning. Either by foot or motor car, they started to make their way to Cathedral Square. Some of those who drove decorated their vehicles with flags, while others wore the colours of the Union Jack in their hats.

Although the armistice that was signed on 11 November 1918 had marked the end of hostilities between the Allied and Axis Powers, the terms of peace had not been officially declared until the Treaty of Versailles was signed on 28 June 1919. With the ‘War To End All Wars’ finally behind them, the people of New Zealand were marking the occasion with three days of peace celebrations.

Saturday 21 July 1919 - Soldier's Day

The first day, Saturday, was Soldiers’ Day.

As they made their way to Cathedral Square on that morning, the citizens of Christchurch would have noticed decorated arches, some adorned with ferns, lining Armagh Street, Cashel Street and Hereford Street. Draped from the balconies of surrounding buildings were the flags of the allied nations. While on the facades of others were displays of illuminations waiting to be lit up when evening approached. Those passing through Victoria Square would have seen naval signal flags imparting the infamous message of Horatio Nelson “England expects that every man will do his duty”.

Upon arriving in Cathedral Square, where the tramway shelter was decorated with a globe accompanied by two British Lions, the crowds then proceeded to King Edward Barracks. It was there, at 10:30 am, that a tribute ceremony was held to honour the returned soldiers.

Despite the organisers having allowed seating for up to two thousand people, many more were still forced to stand. Amidst the songs, the Mayor of Christchurch, Henry Thacker, gave a speech where he reminded the audience of the danger still posed to the free world by the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia, but praised the coming new world being forged in Europe, one of democracy and anti-militarism.

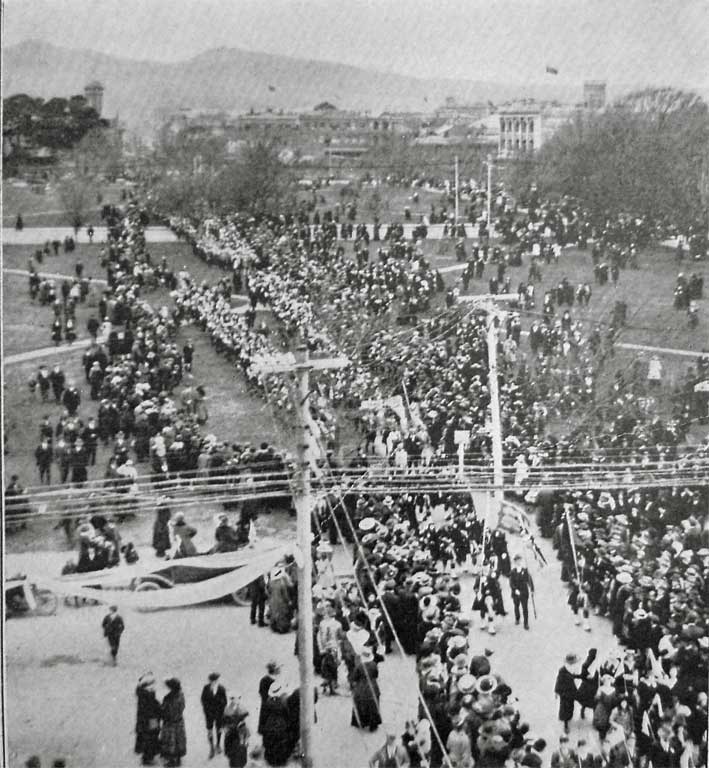

At 2:30 pm a procession of military units departed from the barracks to North Hagley Park, where a parade was held, before the units returned to the barracks.

As night fell over the city, people returned to the streets with anticipation. Unlike other towns in New Zealand which were still affected by the coal shortage, brought about by the war and the 1918 influenza epidemic, Christchurch did not depend upon coal for the generation of its electricity. Being reliant upon hydro-electric power generated at Lake Coleridge, the city was at liberty to make use of illuminations. These were decorations of natural coloured glass, set in lead-light work and mounted in iron boxes which could be connected to an electrical source. Throughout the central city, buildings were lit up with illuminations spelling the words ‘freedom’, ‘peace’ and ‘liberty’. Others showed images such as the Southern Cross, a peace dove or the Union Jack.

Yet the illuminations were not the only light displays. The cinemas which surrounded Cathedral Square used their search lights to brighten the sky, with some operators seeking out groups of ‘flappers’ and ‘fellows’ to settle the lights upon.

If mist had not descended over the Port Hills, then the crowds would have been able to see the bonfire which, like many other peace bonfires across New Zealand, was inspired by a plan for bonfires to be lit all across the British Empire. Fueled by tarred paper, hundreds of motor tyres and kerosene, the bonfire was lit on the Sugarloaf at 6:55 pm.

Five minutes later, a torchlight procession, described by one journalist as being similar in appearance to a “weird pagan procession, with sacrifice to be offered with due rites to a huge squatting idol”, left the fire station on Lichfield Street. Falling in behind the procession, the crowds arrived at the lake in North Hagley Park where they were treated to a display of fireworks and coloured water.

The following Sunday marked the day of thanksgiving. Formal church services were held throughout the city, followed by a peace thanksgivings service at the King Edward Barracks in the afternoon.

Monday 21 July 1919 - Children's Peace Day

The final day, Monday 21 July, had been designated the children’s peace day celebration.

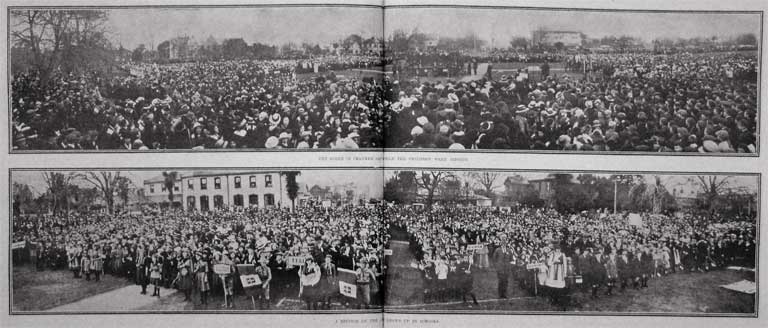

At 9:30 am, groups of children from various schools across Christchurch assembled in Cranmer Square to take part in a procession to represent the various allied nations. Along with flags, some were dressed in costumes to reflect the nation they were assigned (the United States was represented by children dressed as the Statue of Liberty, while some of those representing Japan dressed as ‘geishas’). After singing a selection of songs, the procession proceeded through the city to Latimer Square.

The day closed with another torchlight procession (heralded once more by a bonfire on the Sugarloaf) and a fireworks display at the lake in North Hagley Park. When the display finished at 10 pm many left the park singing and continuing to let off fireworks as they made their way back to Cathedral Square.

Despite the general feeling of goodwill, there were still moments of distress. Throughout the weekend the celebrations were marred by young people throwing fireworks at others, with some causing injuries. Criminal elements also took advantage of the unoccupied offices and factories to break in and rob safes.

However, for those who had lost loved ones or were still dealing with the physical and psychological damage caused by the war, the celebrations offered hope that the future world would be one of peace, a world where war had become redundant.

Find out more

- City of Christchurch, N.Z Peace Celebrations programme

- Read a description of the decorations from The Star newspaper

- Read a description of the illuminations from The Star newspaper

- Find titles about the end of the First World War

Add a comment to: City of Christchurch Peace Celebrations 19-21 July 1919