ChristChurch Cathedral’s deep embrace of its community saved it from the wrecking ball after the Canterbury earthquakes, according to historian Edmund Bohan.

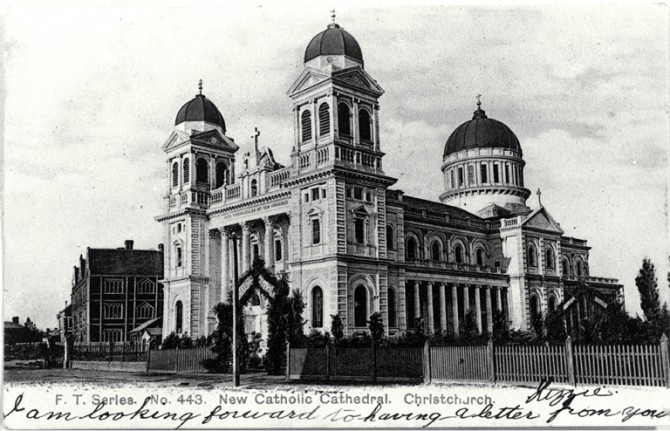

This contrasts with the fate of the city’s other cathedral even though it is considered architecturally superior to the Anglican church in Cathedral Square. The Roman Catholic basilica on Barbadoes Street, was demolished last year.

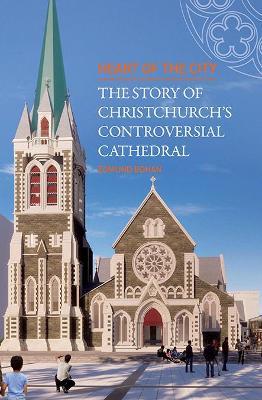

Bohan has written a history of ChristChurch Cathedral, titled Heart of the City: The Story of Christchurch’s Controversial Cathedral, which he hoped would also provide a “journey through a changing Christchurch culture”. I spoke with him recently about writing the history of the controversial church ahead of his book launch in November.

The historian and former opera singer said the Anglican cathedral had become a symbol of the city by the time of the Canterbury earthquakes but the bishop of the time, Victoria Matthews, “did not understand” this civic-church relationship. The then bishop wanted to demolish the cathedral and replace it with a modern church which caused a “colossal row”.

The bishop also had not realised the legal restraints placed on the site by Henry Sewell in the 1850s which meant the Anglican church had a legal obligation to build a cathedral in Christchurch’s main square. This caused legal difficulties when the bishop allocated $4 million from an insurance payout to the Cardboard Cathedral which was constructed in Latimer Square.

The row was only resolved when the Anglican community agreed to restore rather than destroy the building which was a key part of Christchurch’s “healing process” after the quakes, Bohan said.

Tracking the tradition of a city-church relationship

Bishop David Coles, Deans John Bluck and Peter Beck had built strong bonds between ChristChurch Cathedral and its city by opening the Cathedral doors to “all sorts of sects and religious groups” and thousands of tourists in the latter part of the 20th century and early this century. The Christchurch City Council had also been providing $250,000 annually for earthquake strengthening and building repairs.

Hard-liners in the Anglican community were not happy with this open approach with Bluck and Beck causing “fury amongst the evangelicals”. When the Cathedral celebrated Buddha’s birthday “the evangelicals went berserk. They literally thought everything was going to the Devil”, Bohan said.

This openness reflected a tradition that began soon after the cathedral opened in 1904 when Bishop Churchill Julius promoted inclusivity. He wanted the Cathedral to be a “civic shrine” and support community and international events.

Examples of the latter was the support the Cathedral showed for the Antarctic expeditions of Scott and Shackleton in 1901-02 and 1908-09 respectively.

It was this long-standing relationship between City and Cathedral that Bishop Matthews failed to recognise but the civic-church bond ultimately ensured the future of the century-old church.

Superior church demolished

The basilica on Barbadoes Street did not have the same relationship with its city and even though it was widely considered architecturally superior to ChristChurch Cathedral it was demolished in 2021.

“Its destruction was simply decided by a bishop and church that had clear roles and ways of doing things and didn’t need to or wanted to consult with anybody… unlike the Anglican church which had all this support for 30 years.”

After the quake the previous bishop planned to rebuild a part of the Cathedral of the Blessed Sacrament so it was a “great shame that the basilica [which was an excellent representation of Italian Renaissance architecture] simply got pulled down”, Bohan said.

“The loss of that Cathedral is very keenly felt by [New Zealand’s] main heritage groups but there was nothing they could do about it.

“Catholic bishops basically feel they can do what they like as long as they don’t offend Rome. This is very different to how the Anglican church has developed since Henry VIII.”

Bohan, who was raised by an Irish Catholic father and a Scottish Presbyterian mother, perhaps felt a personal loss when the Basilica was pulled down. A former opera singer, he had sung in both cathedrals and said the acoustics were good in the basilica but poor, because of an echo, in ChristChurch Cathedral.

Also, Bohan was near the basilica when the February 22 quake struck in 2011.

“To my horror I saw the whole frontage of the Basilica collapse. It was a terrible sight.”

“We got caught on the one-way system. Within minutes Barbadoes, Tuam and Lichfield Streets were like rivers. It took us three-quarters of an hour to get back [home] to Opawa.”

He agreed with former Attorney-General Chris Finlayson’s view that the better cathedral had been lost but said history was against Finlayson’s suggestion that the Christchurch’s Anglicans and Catholics should set aside their differences and unite under the reinstated church in Cathedral Square.

“Some Anglicans would agree but not the evangelicals.”

There could also be strong opposition amongst the city’s Catholics.

For much of last century Barbadoes Street had an aura of being foreign and anti-British. Many Christchurch Catholics of Irish heritage supported the Irish civil war following the Easter Rising in 1916, deepening the divide between Anglicans of a British background and Irish Catholics. This sectarian sore did not heal until the 1970s and memories of this division counted against Anglo-Catholic co-operation, Bohan said.

‘Some of the descendants might not like what I’ve written’

This and ChristChurch Cathedral’s history of disputes, especially the wrangling after the quakes, made the Cathedral’s history a challenging task for Bohan.

Writing the last five chapters of Heart of the City was some of the most difficult he had written in his career because of all the “warring”, and he did get legal advice before publication. It was easier to write about the past because the “dead can’t sue”, he added.

Bohan’s research revealed some information that could be unpopular with people past and present. “Some of the descendants might not like what I’ve written.”

He found the influence of the Canterbury Association’s original plan was overstated and idealised and there was much dissension about the Cathedral before it was built between religious hard-liners, called “evangelicals” and others who wanted to model Christchurch and its cathedral on Christ Church college in Oxford, England.

“There was internal controversy about everything,” Bohan said adding that debate and dissension over the last 150 years indicated that “nothing had changed at all”.

Canterbury had such a reputation for arguing that it had been suggested the notorious “nor’wester” wind might be to blame and to a “certain extent” that might be true, Bohan said.

Stone-cold blunder

There was also the inconvenient truth that Bishop Henry Harper and Dean Henry Jacobs insisted the cathedral be built from stone instead of wood despite expert advice and seismic activity in Canterbury in the 19th century. “It was a bit of a snob thing. Both of them wanted a solid, stone building.”

“They [the descendants] will know the old bloke [Bishop Harper] made a terrible mistake.”

Proof of this mistake is the wooden pro-cathedral, St Michael and All Angels, which has survived all the seismic activity Canterbury has thrown at it in 150 years.

While ChristChurch Cathedral would be reinstated in stone it would be safer in future earthquakes because the foundations would be able to move with a quake’s seismic forces and leading engineers had been consulted to include earthquake strengthening in the church, Bohan said.

Saving the cathedral meant a valuable collection of Gothic Revival buildings influenced by the 19th century architect Benjamin Mountfort had been saved, he said. The collection included the Arts Centre, the Canterbury Museum, the former provincial buildings and ChristChurch Cathedral.

Heart of the City: A review

Edmund Bohan tracks the dispute-ridden history of ChristChurch Cathedral and provides a detailed and illuminating story of Christchurch’s spiritual symbol.

Edmund Bohan tracks the dispute-ridden history of ChristChurch Cathedral and provides a detailed and illuminating story of Christchurch’s spiritual symbol.

The former opera singer and historian uncovers the nature of the bond between the cathedral and the city and confirms that the relationship is deep and longstanding.

Bohan demonstrates that the dispute between those who wanted to restore the church and those that wanted to pull it down after the Canterbury earthquakes 10 years ago was nothing new. For much of the cathedral’s history there has been vigorous debate about funding, location and what it should be made from.

Bohan also provides insights into the personalities that dominated the cathedral including bishops, deans and a persistent line of irascible choirmasters. He also discusses their beliefs and how they sought to promote them and this helps to explain how the cathedral became so emblematic of Christchurch.

He found that the influence of original planners such as John Robert Godley and their idealistic plan to base Christchurch on Christ College in Oxford, England, was idealised and exaggerated in previous histories of Christchurch. By so doing Bohan has achieved his wish of not only detailing the history of the city’s cathedral but also providing insights into the development of Christchurch itself.

Ngāi Tahu did not feature significantly in this history because Christchurch Anglicanism was dominated by “Anglophiles” until the 1960s and it took “thoroughly modern New Zealanders” such as Coles and Bluck to embrace Māori and Pasifika influences.

Heart of the City concludes with attractive artist impressions of how the cathedral will look when the reinstatement project is complete. The sunken walkways between the Cathedral and the modern-looking visitor and Cathedral centres separate the church and centres and could avoid the bitter dispute that occurred when an adjoining visitor centre was attached to the cathedral in 1995.

Find out more

- More information on the cathedrals of Christchurch.

- Books on the cathedrals of Christchurch.

- Books on Christchurch history.

- Books on Cathedral Square.

- Christ Church Cathedral Reinstatement Project

Add a comment to: Historian Edmund Bohan: City’s fond embrace saved Cathedral from destruction