We all consider ourselves good people, so it can be confronting to realise that we're unwittingly contributing to oppression. For peace of mind it can seem easier to ignore the evidence rather than engage in change, thinking if we cover our eyes then it isn't there, it's all the past, it doesn't affect me. Or we go to the other extreme, demand our education from those we meet rather than listen to those already speaking.

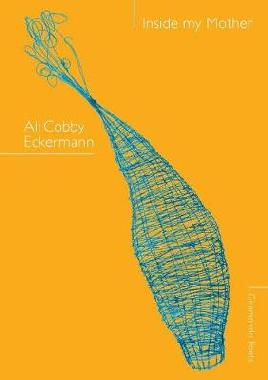

Ali Cobby Eckermann (Aboriginal Australian descended from the Yankunytjatjara language group) and Elissa Washuta (member of the Cowlitz Indian Tribe) are two who are well worth listening to. First Eckermann read from her poem Black Deaths in Custody:

when I walk down this wing and peer

into this filthy room the door closes behind me

the feeling in my heart is changing

from a proud strength of duty to fear

all the stories I have ever heard

stand silent in the space beside me—

a coil of rope is being pushed

under the door of this cell

And Washuta read out her essay This Indian Does Not Owe You, which I recommend reading in full:

When you quiz me on genocide highlights — "Were those smallpox blankets real? I’ve always wondered about that" — to sate your hunger for facts, I do not owe you a free education of the kind that my university students pay for, and I am not so flattered by your interest in my people that I might unfurl a lecture on 500 years of colonization for your edification.

Nic Low asked about the role of anger in writing. Both have been through traumatic experiences - rape, disordered eating, the removal of a child - but are still gentle, kind people in person. Writing provides a safe space for anger. Eckermann brought up the idea of good anger and bad anger, and Washuta responded:

We have that bad anger and what do you do with it? A lot of us just destroy ourselves with drugs and alcohol, because that bad anger has just embedded itself, and then we're told Oh that's all in the past, that was hundreds of years ago, get over it. The reality is that in our communities we are experiencing ongoing colonisation every day, all the time. We are still a colonised people.

Eckermann agreed - they don't want to hurt others, so they hurt themselves. She hopes writing can bring us closer to a collective understanding and healing. By acknowledging pain, maybe some can begin to heal.

Initially I thought I was writing for myself, or for my community, but now I think I'm writing for the future. Poetry is supposed to change and inform lives... I mean statistically we know that one in four women is raped in their lifetime, but we have to share our stories so it's not just statistics, it's life lived. - Eckermann

I wanted to see people like me on the page - I didn't know any other native people at college, I was diagnosed bipolar, raped, had an eating disorder, and to me they all seemed interconnected but I couldn't find anything that reflected my own experience. So my books are a gift to other college students. I knew there had to be other people like me, and there are. - Washuta

How do you feel about your country?

I'd like to remove the culture of denial in Australia. It's been really rewarding going to other countries that know their histories, who aren't afraid of their history. -- Eckermann

There's this cheerful narrative about the brave pioneers who crossed the continent to create something out of the "pristine untouched wilderness" when really people were doing all sorts of maintenance work. The pioneers just didn't understand how the land was being used, or couldn't see it. But it's always "It's really nice that the Indians helped the settlers make something out of this super boring place." -- Washuta

The session ended with a plea for greater friendship and connection in the face of the tsunami of racism that seems to be washing over the world.

So listen to others. Be kind. And go read their books.

Add a comment to: Sister Cities/First Nations – WORD Christchurch