On 24 December - Christmas Eve - 1953, the Wellington-to-Auckland express train derailed at Tangiwai in the central North Island.

On 24 December - Christmas Eve - 1953, the Wellington-to-Auckland express train derailed at Tangiwai in the central North Island.

Christmas Eve 1953 was a fine night, after a day without rain. There was nothing to show that the Whangaehu River would be in flood when the Wellington-to-Auckland express was due to cross the rail bridge at Tangiwai (the name Tangiwai means weeping waters in Māori.)

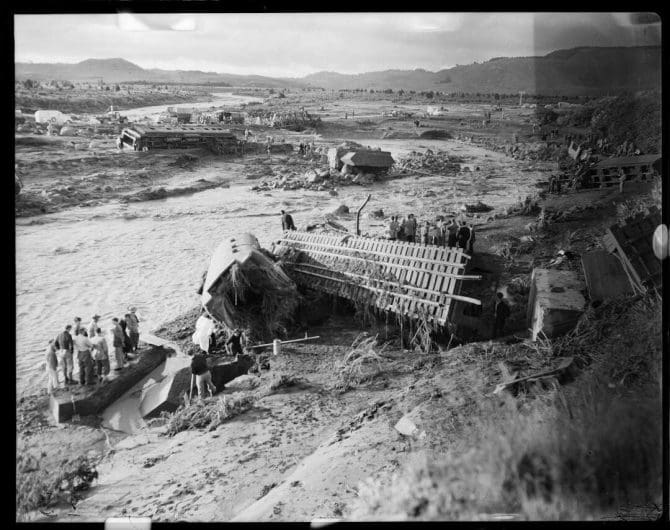

When part of the wall holding the crater lake of Mount Ruapehu collapsed, a huge flood of water and silt, known as a lahar, flowed down the side of the mountain carrying uprooted trees, rocks and ice into the Whangaehu River. A giant wave of water, mud and rocks 6 metres high hit and swept away one concrete support of the rail bridge at Tangiwai, almost 10 kilometres from Waiouru.

At 10:21 pm the express, consisting of one engine, nine carriages and two vans, and travelling at about 60 kilometres per hour, rocketed onto the weakened bridge. As the express left the bank, the rest of the bridge collapsed and the engine nose-dived off the edge into the air, almost hitting the opposite side.

The first five carriages followed, catapulting upwards before plummeting into the floodwaters. Four of these carriages were broken up by the force of the river waters, with little hope for the passengers.

The sixth carriage teetered on the edge of the ruined bridge while Cyril Ellis, whose car had stopped at the submerged road bridge, and the train's guard, William Inglis, climbed in to warn the passengers and move them to the carriage behind. Almost at once the carriage broke free from the remaining carriages and fell into the river, where it rolled downstream before coming to rest.

Ellis, Inglis and a passenger, John Holman, managed to get all the passengers, except for one, out through the broken windows and onto the side of the carriage. As the level of the floodwaters dropped, the survivors were able to form a human chain and make their way to the bank.

Meanwhile passengers from the other carriages in the river struggled from the wreckage and made their way or were helped to the bank. Some freed themselves only to be swept further downstream before being able to crawl ashore. Many were drowned or smothered by the thick silt in the river, and some were swept downriver and out to sea, their bodies never recovered.

On the opposite side of the river, Arthur Bell and his wife had stopped at the flooded road bridge and saw the express crash into the river. While Mrs Bell went for help, Arthur helped rescue survivors from the carriage which had landed on the river embankment.

Soldiers from the army camp at Waiouru joined forces with local volunteers, but rescue was difficult and dangerous. The water was full of debris - rocks, trees and wreckage from the train - and still flowing with enough force to knock people from their feet. Oil and silt covered passengers and rescuers alike.

Soldiers from the army camp at Waiouru joined forces with local volunteers, but rescue was difficult and dangerous. The water was full of debris - rocks, trees and wreckage from the train - and still flowing with enough force to knock people from their feet. Oil and silt covered passengers and rescuers alike.

The rescue operation soon became a body recovery operation. Of the 285 people on the train that night, 134 survived and 151 died, most drowned in the floodwaters.

The last three carriages had come to a halt before they reached the bridge. It was later discovered that the train had been able to brake before it hit the bridge, undoubtedly saving a number of lives.

Bob Blair and Nerissa Love

Cricketer, Bob Blair was playing for New Zealand in South Africa when he got the news that his fiancée, Nerissa Love, was one of those killed in the Tangiwai disaster. He was not expected to play in the Boxing Day test at Ellis Park but came into bat after the fall of the ninth wicket anyway. A book about the incident, What Are You Doing Out Here: Heroism and Distress at a Cricket Test by Norman Harris, was published in 2010. A movie about the couple and the tragedy, Tangiwai: A Love Story, was made in 2011.

How many died?

151

20 bodies were never recovered and were thought to have washed out to sea, 120 kilometres from the bridge.

Other events and outcomes

The noise of the disaster was loud enough to be heard 10 kilometres away at Waiouru.

Because no newspapers were produced on Christmas Day, the first detailed news of what had happened was given in a radio broadcast by the Prime Minister, Sidney Holland, from Waiouru Camp. Queen Elizabeth and Prince Philip were visiting New Zealand when the disaster at Tangiwai happened. Queen Elizabeth made her Christmas broadcast from Auckland, finishing with a message of sympathy to the people of New Zealand. Prince Philip attended a state funeral for many of the victims.

Cyril Ellis and John Holman were awarded the George Medal, for their bravery, and Arthur Bell and William Inglis were awarded the British Empire Medal.

A commission of enquiry found that a lahar or mudflow was responsible for the disaster. After the collapse of the crater wall the Mount Ruapehu crater lake level had dropped by 6-7 metres, meaning that approximately 2 million cubic metres of water had flooded into the river and hit the Tangiwai bridge with the force of a tidal wave. The flooded river was at its highest point when the express crashed into it. A mixed goods train had crossed the river about three hours earlier when it was still daylight, and the river had appeared normal then.

Later investigation has suggested that the bridge had been weakened by an earlier lahar flow in 1925, and that warnings by amateur geologists about the state of the crater wall should not have been ignored by the authorities.

At the time, Tangiwai was the eighth biggest railway disaster the world had seen. It is still the fifth worst disaster in New Zealand's recorded history. On Christmas Eve each year the express train slows as it crosses the new bridge across the Whangaehu River, and the driver throws a bunch of flowers into the water. A card reads: "In memory of all who died at Tangiwai on Christmas Eve, 1953."

More information and sources

- Find information in our collection about the Tangiwai Rail Disaster

- Tangiwai railway disaster from NZHistory

- Almost 60 years but Bob Blair never forgets Stuff, 13 June 2013

Disasters

- Go to our page on New Zealand disasters

- Read some true kids books about disasters

- Read some true adult books about disasters

- Read some stories about New Zealand kids in disasters