If one wants to derive personal pleasure from piano playing, one may just play.

If one wants, however, to give pleasure to others, one must never stop working.

(Ignacy Jan Paderewski)

Ignacy Jan Paderewski, the first superstar of the 20th century, one of Poland’s first Prime Ministers, and a man hailed the world over as a genius on par with Chopin or Einstein, is now a figure largely forgotten.

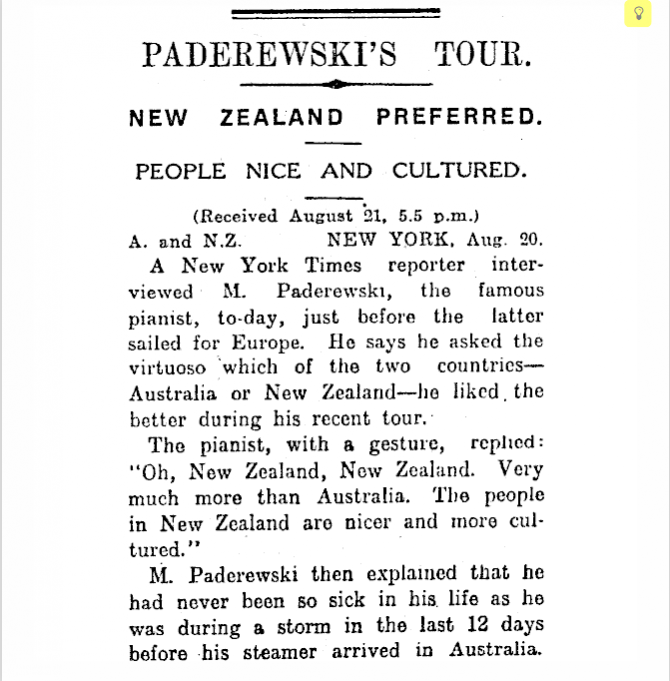

In his day the pianist held performers and royalty alike spellbound, with tours that spanned from Africa to Australia, through to Europe and every state of America. Women fainted in his presence, he was mobbed in London, Paris and the States, and even critics such as James Huneker had to admit to being 'totally overwhelmed' by his performances. He was one of the world's first solo performers, renowned for conjuring varied and beautiful tones, akin to an orchestra. His recitals were described as spiritual experiences, and the eye catching maestro as a sort of Samson whose musical prowess stemmed from his magnificent mane of red hair.

In spite of the public adoration (and often hysteria) Paderewski was also respected by world leaders from Lloyd George to Woodrow Wilson. He was admired for his intellect and diplomacy, and was instrumental in securing his country's independence after the first world war.

Author Jacek R Drecki will bring this forgotten man to life with the launch of his book ‘'Ignacy Jan Paderewski, A Pianist Amidst the Geysers'.

Ignacy Jan Paderewski, A Pianist Amidst the Geysers

Thanks to 'Between the Waters - Polish Legacy in NZ Charitable Trust', Quo Vadis Publications, and the Polish Embassy in Wellington, Christchurch will have the opportunity to hear Drecki discuss Paderewski's remarkable story at Tūranga on Saturday 19 October.

While Dreicki's work celebrates Paderewski, the man, he also draws on the story of New Zealand. His extensively researched work, looks at contemporary stories of Paderewski's phenomenally successful New Zealand tour, as well as Paderewski's own recollections of his visit. Paderewski toured New Zealand twice, performing across the country (from Auckland to Invercargill) in 1904, and visiting again in 1927. Always a great philantrophist (he donated to many causes during his lifetime including a fund for Jewish refugees from Germany, and the Paderewski fund for American composers (gifted regardless of race or religion)), Paderewski donated the money from his last concert in Wellington to the wounded New Zealand soldiers of the First World War. He was impressed not only by the interest in classical music displayed by the population of New Zealand but also by the people he encountered along the way. He recorded his meetings with Pākehā and Māori alike including recollections of Makereti Papakura, the New Zealand entertainer and ethnographer herself:

"Our guide was a Maori girl bearing the poetic name of Maggie Papakura. She was quite a lady—well-educated. She was recognised chieftainess of that little tribe and she always offered, most graciously, her services as guide to that delightful land. She published an interesting book later about the district of Whakarewarewa. She guided us most carefully. She would take my wife by the hand, and then to me, following, she would say, “Now be careful, very careful. Don't go to the right. Just follow me exactly.' I asked why. ‘Because there is an abyss here which you cannot see. It is boiling mud—it is on your right, only a yard away. So be very careful.’ And then she threw in, by way of warning, ‘A few years ago my aunt made a mis-step and sank into that abyss, and disappeared for ever.’ Well, I can assure you that I followed her advice! I was very careful."

As perceptively observed by Tom (from 'Between the Waters - Polish Legacy in NZ), the stories of New Zealand and of Poland are very much intertwined, making Drecki's work remarkably apt :

"New Zealand really became New Zealand, not just a colony of Britain, after the war, just as Poland became its own country and re-gained independence. They both made tremendous sacrifices and fought side by side. There is a history there and an affinity between our countries- but while one country lost so much from the war, one (Poland) re-gained its independence back".

Of course, Paderewski himself was there at the dawn of Polish independence so would have recognised the parallels between the two countries better than anyone. The world's finest pianist sacrificed his phenomenally successful career to lead his country through to a new beginning. In 1919, Paderewski was asked by chief of State J Piłsudski, to form a government. As historian Adam Zamoyski has written:

"Paderewski rose to the occasion brilliantly. His energy and physical endurance could cope with the hectic nature of his day to day existence; his extraordinary memory for facts, figures, and faces stood him in good stead when quick decisions were required; his personal charm and magnetism smoothed many ruffled feathers, while his presence and authority imposed itself over stormy meetings". Paderewski was a true patriot, and had been made aware of Poland's predicament from a young age. His father, Jan Paderewski, was involved in the 1863 insurrection when he hid arms for the insurgents, and of course he was daily reminded of his country's misfortunes by the scenes around him. As his biographer Adam Zamoyski again noted: 'To become somebody is the ambition of many a proud child born into the conditions of humiliation and poverty; to help Poland in this case was the equivalent to helping everyone he knew'"

To be Poland's leader at such an integral moment in its history was of huge importance to Paderewski, and he threw all his energy into the task of negotiating with the other leaders of Europe, including US President Herbert Hoover and British PM Lloyd George. There is a lovely story, told by radio correspondent Helena Sowinski, that perfectly illustrates both Paderewski's dedication to causes, and his generosity:

"In 1892, an 18 year old student at Stanford University was struggling to pay his tuition. He was an orphan and had no relatives to ask for money. With few options available, he and a friend came up with a bright idea. They decided to host a musical concert on campus to raise money for their education.. They reached out to Paderewski, who was then touring in the US. His manager demanded a guaranteed fee of $2,000 for the piano recital. A deal was struck, and the boys began to work to make the concert a success. The big day arrived, but they had not managed to sell enough tickets. Their total collecton was only $1600.. Disappointed, they went to Paderewski and explained their plight. They gave him the entire $1600, plus a cheque for the balance of $400. They promised to honour the cheque as soon as possible."

"No,"said Paderewski, "This is not acceptable." He tore up the cheque, returned the $1600 and told the boys to use the money to cover their fees, and return only the money that was left over to him. The boys were surprised and thanked him profusely.

Many years later, Poland was ravaged by World War 1, and one and a half million people were starving. There was no money to feed them, and Paderewski, then Prime Minister, reached out to the US Food and Relief Administration for help. The CEO there was a man called Herbert Hoover (later President Hoover). He agreed to help and quickly shipped tons of grain to relieve the starving Poles. Paderewski decided to go across to meet Mr Hoover and thank him personally. When Paderewski began to express his gratitude, Hoover said, "You shouldn't be thanking me, Mr Prime Minister. You may not remember this, but many years ago, you helped two young students go through college. I was one of them."

Sadly Paderewski's time as Prime Minister of Poland ended just after 10 months. He continued on his work at the League of Nations for another six months, his diplomatic skills as well as his ability to speak seven languages, being a valuable asset in Poland's efforts to negotiate often delicate agreements. After five years of rarely touching a piano, Paderewski then returned to the stage, (largely due to his decline in finances since taking the premiership of Poland). Clearly age had not staled his performance or his charm. Following his performance in Wellington, the New Zealand Press reported that indeed he had aged but "only as a fine wine does". He performed Chopin and other composers, as well as some of his own compositions (Paderewski incidentally composed a generous amount of neo-romantic works, which enjoyed some popularity during his lifetime).

So why is such an important figure in his day now largely forgotten?

In his biography on Poland's national hero, Adam Zamoyski offers a possible explanation for this, with a story from the great pianist's first significant performance. Upon hearing the young Paderewski play for the first time, a French Duchess expressed her wonder: "Maestro, it was sublime! now that I have heard you, you can die!" . While Paderewski went on to live for another 53 years, Zamoyski notes that the Duchesses words were strangely apt: " While he was billed for immortality in his lifetime, his fame died with those who knew him; he turned out to be only a transient mortal".

In his biography on Poland's national hero, Adam Zamoyski offers a possible explanation for this, with a story from the great pianist's first significant performance. Upon hearing the young Paderewski play for the first time, a French Duchess expressed her wonder: "Maestro, it was sublime! now that I have heard you, you can die!" . While Paderewski went on to live for another 53 years, Zamoyski notes that the Duchesses words were strangely apt: " While he was billed for immortality in his lifetime, his fame died with those who knew him; he turned out to be only a transient mortal".

With Drecki's new work, he gives us an opportunity to remember and pay tribute to a remarkable man, politician, and musician whose musical and diplomatic legacy can still be felt in not only Poland but right around the world, whether we are aware of it or not. In addition, he gives readers a look back at a fascinating moment in history, where the national hero of Poland played his tribute to the post war nation of New Zealand.

A special thanks to Dorota of 'Between the Waters- Polish Legacy in NZ Charitable Trust’, for all her input in the writing of his post.

Further information

- Listen to the music of Paderewski

- Find more titles about Polish people in New Zealand

- Plains FM: Polish Waves

- 'Ignacy Jan Paderewski – A Pianist Amidst The Geysers' by Jacek Roman Drecki

- Timeline of Paderewski's life Paderewski Festival website

Add a comment to: Paderewski: Poland’s Prime Minister and superstar pianist