“E Pāpā Waiari, taku nei mahi, taku nei mahi hei tuku roimata…”

The last day of WORD Christchurch Festival always produces a buzz, and this was to be no exception. A diverse audience gathered in the Phillip Carter Family Concert Hall at The Piano in anticipation of the hour that was to come. Aspiring writers, friends of various societies and even former politicians, all had come to listen to a man who had touched their lives in different ways.

The lights dimmed as the Hall filled with rousing applause as Witi Ihimaera joined Arihia Latham on stage. The following hour was a walk though his memories of books and times past – as he called it “speed dating with Witi Ihimaera”. He provided a wonderful, intriguing insight into what has inspired and driven his writing.

By in large, Ihimaera is a self-professed literature activist. Preferring to be called an artisan rather than an artist, he began writing as a means to “subvert European assumptions and expectations of Māori.” Disillusioned as a schoolboy by the malevolent undertone of Aotearoa | New Zealand literature written by Pākehā about Māori, Ihimaera took it upon himself to become a writer and “write a book of short stories about Māori that every school kid would have to read, and that book was Pounamu, Pounamu.” Ihimaera in his own words noted that “even at a young age he was already intuitively reaching out to write the alternative Māori story and to creating tino rangatiratanga for the Māori text.”

The driving force of his writing is his need to represent Māori truthfully, viewing the simple act of putting pen to paper as not only “an act of recovery and a revolutionary act but also more importantly a rehabilitative act.” At a time when Māori had been made invisible in New Zealand, Ihimaera saw his writing as a Treaty of Waitangi act of reclamation. “Wanting to establish a Waitangi Principles of equity, equality and justice for Māori” he has used his work as a platform to highlight the inequity, inequality and injustice that Māori face.

Always a fast writer, he completed his first three books, Pounamu Pounamu, Tangi and Whānau within three months in 1970 while in London. However, he reminded us that it would take a further two years before he would be published. This was a time when Māori fictional writers of Māori fiction were unheard of. Nevertheless, 1970s and 80s, as he remembers, was a period when “we [Māori] began to find our own tongues, mana and tino rangatiratanga.” Referred to as the Māori renaissance, Ihimaera recollects the term as being “a comfortable way of putting Māori advancement in a cultural lens rather than a political one.” The truth is that this period was in fact a political-cultural revolution. As Ihimaera proudly states, Māori art practices – particularly visual and written were finding a place in a largely Pākehā dominated space.

Māori artists such as Ralph Hōtere, Buck Nin, and others, “not accepted by a traditional fraternity”, like Ihimaera, openly challenged those fraternity with the metaphorical political messages contained within their work. Again, they like Ihimaera, subverted Pākehā assumptions and expectations of Māori. That being said, Ihimaera notes the concern within te Ao Māori that writing was taking the art practice from the traditional. Thus the 70s and 80s were filled with discussion as to whether these art practices were traditional or contemporary. By the 90s, Ihimaera notes the discussion had moved past this point, with a consensus that Māori art is inspired by the traditional.

From his earliest works, his whānau members have been central characters. Morphing into the Mahana whānau, they have appeared as central characters in the majority of his work. A deliberate act, Ihimaera was determined “to put a Māori whānau going head-to-head with Katherine Mansfield’s Pākehā family at the centre of Aotearoa | NZ literature.”

His whānau continues to play a huge role in his life. The perpetual support of his Father and his worldview that “the entire world was Māori” imprinted on Ihimaera from a young age and it is this non-binary philosophy that Ihimaera himself embraces. Perhaps the biggest influence in his life has come from his mother, nan and aunt. Having observed the sexism and the role of men and women of the time, he learnt from a young age, “women in those days had to find their own sovereignty.” It is this sovereignty he has championed in his books with his lead female character based on one of those key three women.

But in spite of his inclusive perspective he has still encountered gate keepers from both worlds. Māori, as he wrote fictional Māori into existence at a time when they had only viewed themselves as non-fiction or real, and Pākehā as he “climbed the colonised Poutama of publishing which he changed along his way.” The 70s and 80’ was a time of ‘walking the talk’, Ihimaera and others became a toki, referred to by Latham, that cut paths for those that were to follow. Ihimaera acknowledges that at times it was difficult but gained strength from Ngā Puna Waihanga – Māori artist and writers collective who formed during this period. In spite of backlash from some corners of the wider community, they accepted the need to be transgressive as they were “doing it out of love for future mokopuna.”

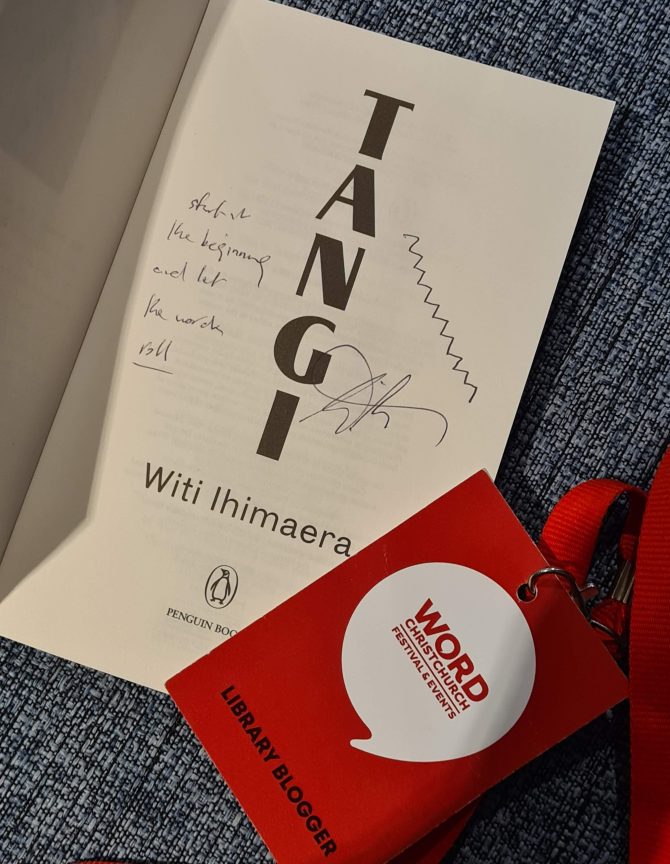

Tangi for Ihimaera, was one such transgression. Wanting to prove Māori could excel in the Pākehā literary arts, the book, published in 1973, was awarded the Wattie Book of the Year in 1974. In Ihimaera’s words he was a “young man trying to figure out the strategies to recreated Māori concepts with instructional, theoretical and linguistic European assumptions". He wanted to subvert the idea of the European novel. 2023 is the 50th anniversary of the book’s publication and to commemorate this, Ihimaera has revised the book. In its third reiteration, he placed the tangihanga | Māori funeral ceremony as the central frame of the story. His reasoning, “with an exclusively Māori ceremony at the centre of the story, it would force him to write in accordance with the concepts of whakapapa in lyrical strokes that would imitate waiata tangi.” In doing so he hoped to create poetic prose of a Māori story in a Māori setting with Māori characters rather than just a novel.

Ihimaera is proud that he uses Māori methodology more than Pākehā methodology when writing. Aroha, ihi, mana are his key muses with a large dash of wehi | provocation, “to give [his] work the sharp political edge that some people don’t like.” It is these things he believes “that makes his work truly indigenous [particularly having] the wero there, right through the centre of the work.” Writing overseas was important to him as it afford him the opportunity to “objectivise the country and what was happening to it [thus] enabling him to do that subjective / objective glance to come to some sense of authenticity and truth.” Some of his best works were created overseas, Pounamu Pounamu, & Tangi in London, Bulibasha in France and Whale Rider in New York and for a while, he jokes, he thought of himself as self-imposed exiled writer.

At one-point Ihimaera reminisces about his first ever literature festival appearance following the publication of Tangi here in Christchurch. Noting he owes a debt of thanks for those Festival Directors believing in him and to some degree helping launch his writing career. The nostalgia is not lost on him as he sits here some 50 years later discussing not only his career but also the revised publication of that very book.

Ever the diplomat, Ihimaera has a refined gentleman air about him which no doubt his 15 years with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs cultivated. His writing going into a hiatus until he had left Foreign Affairs, Ihimaera set about embedding tikanga Māori in the foreign spaces he worked. But his passion for writing could not be quailed and upon leaving Foreign Affairs he picked up his metaphorical pen and the rest as they say is history.

Over the hour, Latham gently guided the conversation through the stacks of Ihimaera’s memories, pausing here and there to reflect, recall and reminisce of times gone by, of friends and of course whānau. Love him or hate him, you can’t deny Ihimaera has played a large role in Aotearoa | New Zealand literature. He has not only pathed the way for but also inspired many Māori fiction writers.

Through his early books he provided a safe platform for a generation of Pākehā to learn about Te Ao Māori in a non-threatening manner at a time when Māori were considered invisible or assimilated. 50 years on, many of that generation joined me in the warmth of the Chamber on a chilly Sunday night. The hour concluded as it started, with Ihimaera reading from Tangi.

“Āue, āue, ka mate au, e hine hoki mai rā…”

Photos of the Witi Ihimaera event

Find out more

- WORD Christchurch website

- Follow @WORDChCh on Twitter

- Follow WORDchchon Instagram

- Like WORD Christchurchon Facebook

- Listen to WORD Christchurch podcasts

- Our WORD Christchurch 2023 page

Add a comment to: WORD Christchurch 2023: 50 years of Witi Ihimaera