In a garden, expertise was personal and anecdotal – it was allegorical – it was ancient – it had been handed down; one felt that gardeners across the generations were united in a kind of guild... there was no quarrelling with the laws and tendencies of nature, no room for judgement, no dispute: the proof lay only in the plants themselves, and in the soil, and in the air, and in the harvest.

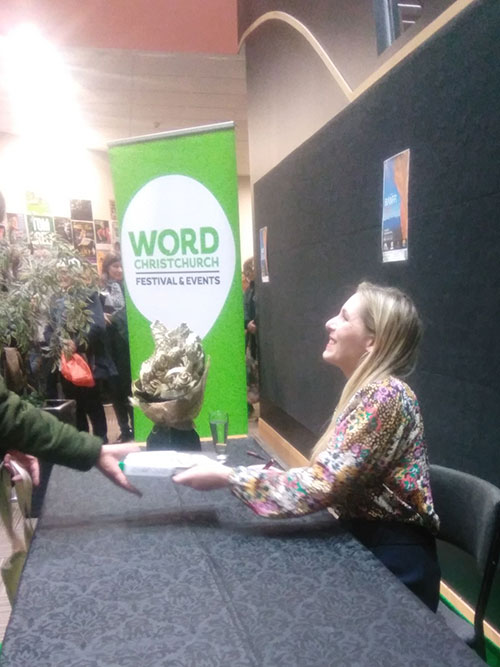

Eleanor Catton's Birnam Wood is a hugely entertaining modern story with Shakespearean proportions. And a tip of the bonnet to Jane Austen's Emma. Last Wednesday Catton came back to her (sold out) former high school, Burnside High, to chat with former WORD Christchurch director, Nic Low.

Birnam Wood is literary, unemotive and very readable. Written in a stream of consciousness reminiscent of Virginia Woolf, Catton's characters expound illustriously on their beliefs and politics. Her text combines serious issues with ironic humour – and gardening tips.

Birnam Wood's cleverly plotted story is a great hook: a Community Gardens venture gone a bit rogue; presenting legally sanctioned projects to the public eye, while populating, seeding and trespassing on lands to raise veggies as a political act.

It's a response to the political climate at the time of writing, says Catton. In 2017 Trump had risen to power, Britain was navigating its way through Brexit and norms were crumbling: "...an unknowable future rushing towards us." Catton looked towards Shakespeare's Macbeth, feeling the play might have something to say about this moment.

Macbeth, says Catton, is not a character you identify with. The play is not so much about ambition, as 'self-blindness' - Macbeth rushes into a prophesied future, seduced by the certainty of success - which is his downfall. It's a position that holds relevance for all of us:

"Within every certainty there can be an enormous blindspot."

Other influences colouring Catton's approach to this book was her recent work on screenplays such as the Luminaries adaptation, and a new version of Jane Austen's satirical novel, Emma.

Catton wanted to satirise New Zealand's relationship with property, while creating a tragedy with an ending that was both totally surprising and inevitable, "...with a high body count." What makes it tragedy, says Catton, as opposed to nihilism, is the fact that the outcome could have been changed, had the characters made different choices.

She enjoyed the god-like feeling of being able to pull the strings of her characters – pitting a billionaire against activists – a collision of characters with very different lives, brought together in an way that asks, "how can the characters get out of this?"

Catton's cast of characters are so entrancing, I forgot about the plot for a moment. They all have a little piece of Eleanor Catton in them. "I needed it to be a personal piece, or the satire would fail." Catton flipped her view around and "satirised the things I loathe about myself."

Central protagonist Mira Bunting is a radical with a clever mind to match her sparkly-eyed idealism. She bites off a bit more than she can chew when she engages with an investor representing the interests of the latest property she's set her sights on – a farm called Korowai, above a town called Thorndike – cut off by an earthquake induced landslide. It's land languishing when it could be productive, feeding the needy.

"We are a grassroots community initiative...We plant sustainable organic gardens in neglected spaces, and we are committed to the principles of solidarity and mutual aid."

The foil to Mira's vain, self-obsessed idealist is her right-hand woman, practical and skilled organiser Shelley Noakes, perhaps the brains of the operation. Shelley wants out - after years of being taken for granted - but the next venture is about to change everything.

Enter Tony Gallo, Mira's former flame:

'Tony had no difficulty whatsoever in believing the New Zealand government capable of rank conspiracy. What was the Cabinet anyway, he thought, his indignation rising, but a cabal of millionaire property tycoons who had spent their time in office beefing up their personal stock portfolios and actively discouraging the populace from turning out to vote?? Most of them could hardly breathe without lying.'

Tony, a joy to create, says Catton, is an over-opinionated traditional Marxist who, in his late twenties, is dissatisfied with where the political conversation has gone. Its become fractured, the left 'left behind.' At Burnside, Catton reads aloud a brilliant debate between Tony and Mira, who will not capitulate to his superior verbosity.

Which brings us to Mira's benefactor, Robert Lemoine. She's in thrall to him. He's bought Korowai, a generational farm in the wilds of Southland, from a newly-appointed Lord and Lady: the Darvishes. He has the means to help the Birnam Wood collective to finally 'break good'.

Yet Lemoine is the antithesis of everything she believes in - a billionaire who's made his money from drone surveillance. Has Mira's overconfidence, like Emma before her, lead to her ultimate mistake?

Lemoine is a sinister figure playing the philanthropist, supposedly building a bunker for the end of days, all the while surveilling his new prodigies. Catton paints him in a sinister light: the security mogul suddenly invested in a grassroots collective. It's rumoured he's based on Peter Thiel, owner of PayPal.

With Lemoine, Catton wanted to write a bad character sympathetically. Traditionally, we're locked out of a baddie's consciousness, says Catton. Although he's a psychopath, performing subterfuge, we read his point of view. Catton found a 'swagger' in herself when writing him. A caricature, Catton tried to find humanity in him, while the other characters become the reverse.

Catton is able to explore the theme of technology and surveillance through Lemoine's character: not 'Big Brother' aka the government, but 'Big Business' is watching us. Add a sprinkling of automatic weaponry, some black SUVs, automatic weapons and the story begins to taste like an international thriller.

Through this character, and the Darvishes, Catton highlights how New Zealand's economy, with its lack of a capital gains tax, really favours wealth and inequality.

"An algorithm has an agenda, a for-profit agenda that it is hiding from you, very much like a psychopath does, and it is also manipulating you, it's flattering you into showing you things that it thinks you want to see. It's matching itself to a version of you that it wants you to like."

Catton also elaborated on the theme of surveillance in Birnam Wood; a comment on the cost of the technology that fuels our modern existence: Lemoine uses drones to enact a subterfuge, while the guerilla gardeners are glued to their phones, surveilling each other. Tony practices camouflage and stays off the internet in an attempt to evade discovery. As in Emma, readers are seduced by the text into feeling morally superior: which of course leads to their chagrin.

Lemoine may have information, but he doesn't have knowledge: he underestimates the depth of the bond between Sir Owen and Lady Darvish, the former owners of Thorndike. Their deep understanding and surveillance of each other after a lifetime together is a saving grace, while their capitulation to Lemoine's non-disclosure requirement is a vain and dangerous indulgence.

There was a huge show of hands when Nic Low asked how many of the seven-hundred plus crowd had read this book. If you're not one of them, join the conversation.

Find out more

- Stuff: Eleanor Catton: The dark agendas that led to her new novel

- Eleanor Catton on RNZ: 'Going online is not an innocent act...': One of the themes of Birnam Wood is the cost of the technology that surrounds our everyday lives. - Catton talks about the media furore after The Luminaries, and twitter-as-addiction

- The Bookshop Band: Birnam Wood

Add a comment to: Birnam Wood: Eleanor Catton comes to Burnside