"I am writing to you at the end of a fortnight of very hard work, for I have just gone through my first experience in changing servants; those I brought with up with me four months ago were nice, tidy girls, and as a natural consequence of these attractive qualities they have both left me to be married."

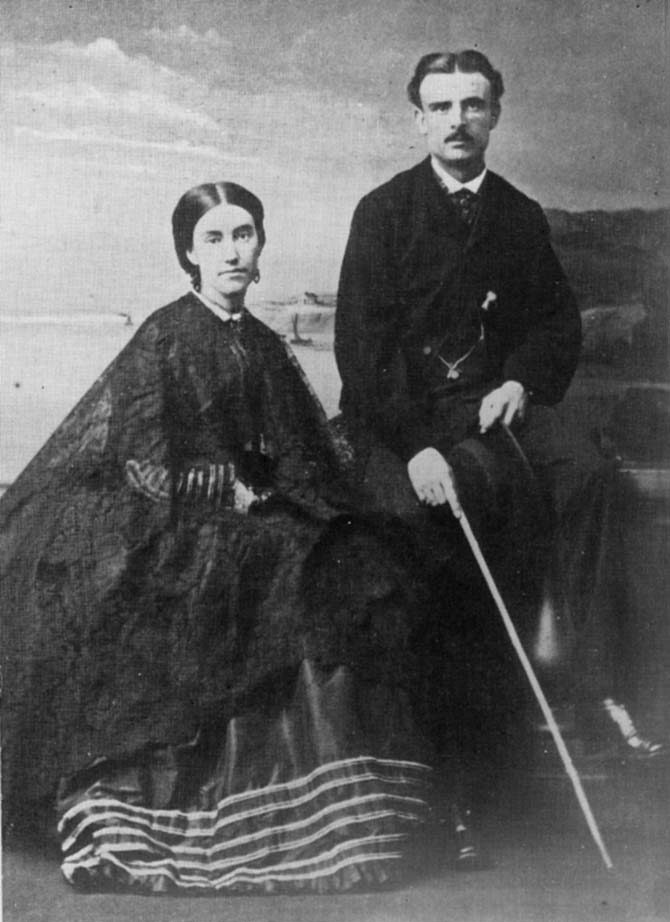

This is how one of the funniest letters I've ever read begins. The writer is Lady Barker, she's in her mid thirties, it's 1866, and she's not long arrived in New Zealand. She's adventurous, witty, and I'd have loved to have met her although I suspect, after reading all of her letters, that I'd have trouble keeping up. She was born in Jamaica, educated in the UK, lived in India with her first husband, and at time of writing giving it a jolly good go on a sheep station in Canterbury with her second husband, Frederick, who is eleven years younger than she is. Both her children are, sensibly, at boarding school in England.

The letter continues to describe the farce that struck her Malvern Hills household in the wake of the servants' departure:

"In the meantime we had to do everything for ourselves, and on the whole we found this picnic life great fun. We were all equally ignorant of practical cookery, so the chief responsibility rested on my shoulders and cost me some very anxious moments, I assure you."

Frederick "ate my numerous failures with the greatest good humour; the only thing at which he made a wry face was some soup into which a large lump of washing-soda has mysteriously conveyed itself."

Later in the letter she goes on to describe an 'incident' with her bread. It is, to put it mildly, explosive.

Her letters cover the scope of what life was like on a sheep station in the 1860s, with insights into pioneering humour and character, language and culture. In one letter she laments the fact that the "rapid advance of civilisation precludes the possibility of being really uncomfortable; this makes me feel like an imposter". She feels like she has missed out on the hardships that the pilgrims, when they arrived on the 'first four ships' sixteen years before, went through with "such spirit and cheerfulness" and because of this she convinces her husband and a few of his friends to camp out in the wilderness - up on top of 'Flagpole', a hill 3000 feet above sea level, in April.

Her letters cover the scope of what life was like on a sheep station in the 1860s, with insights into pioneering humour and character, language and culture. In one letter she laments the fact that the "rapid advance of civilisation precludes the possibility of being really uncomfortable; this makes me feel like an imposter". She feels like she has missed out on the hardships that the pilgrims, when they arrived on the 'first four ships' sixteen years before, went through with "such spirit and cheerfulness" and because of this she convinces her husband and a few of his friends to camp out in the wilderness - up on top of 'Flagpole', a hill 3000 feet above sea level, in April.

To put it mildly - their night was not a comfortable one, despite the two bottles of whiskey they'd packed (and a tiny bottle of essence of lemon, for making toddies) among the five of them.

The nights she spent running about the hills setting fires, "or as it is technically called 'burning the run'" sound like much more fun. The old grass needed burning off and, despite almost losing her eyebrows a few times (and having to take extra care not to wear an inflammable petticoat) she enjoyed it immensely. In the height of the burning season her friend Alice came to stay and "to my great delight I found that our tastes about fires agreed exactly, and we both had the same grievance - that we never were allowed to have half enough of it; so we organised the most delightful expeditions together." These involved a great deal of burning interspersed by tea and cake, two wild ladies roaming the Malvern hills together having the time of their lives.

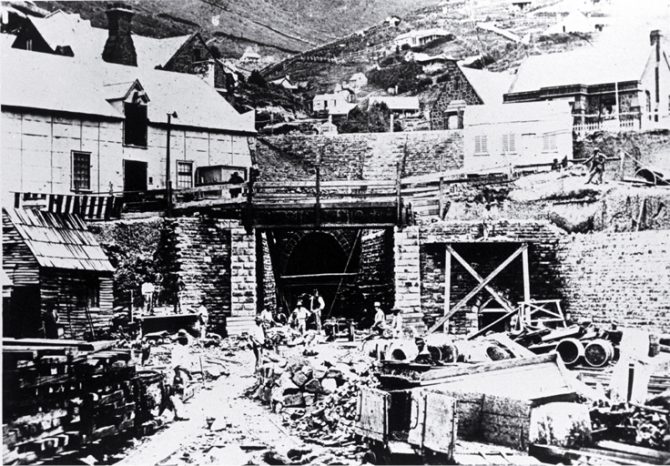

There are some great comments about life in Christchurch from her point of view. The Lyttelton tunnel was half finished when she and Frederick arrived (in October 1865) but she was still impressed: "it seems wonderful that so expensive and difficult an engineering work could be undertaken by such an infant colony.

However "I am disappointed to find that the cathedral, of which I had heard so much, has not progressed beyond the foundations". In fact it would be ten more years before the first service was held in the cathedral and even more years after that when it finally got its roof – nothing about our cathedral has ever happened quickly!

The book of her letters, Station Life In New Zealand is a fantastic read, funny and insightful. Though it is at times heartbreaking, every hardship (death, floods, snowstorms, a very close call with a wild pig) is approached with a brilliant strength of character.

In short, she's a hoot.

-

Read our biography of Mary Anne Barker on our website, or on the Dictionary of New Zealand Biography.

Read our biography of Mary Anne Barker on our website, or on the Dictionary of New Zealand Biography. - Read biography

- Search for more books by Mary Anne Barker in our catalogue.

Add a comment to: Life on a sheep station in the 1860s – more hilarious than you might think