During the early years of the 20th century, voluntary libraries flourished in Christchurch. Public library services were the responsibility of Canterbury Public Library, which was managed by Canterbury College, and based in Cambridge Terrace in the central city. For those unable to visit the city regularly, however, library access was limited. Financial constraints did not allow the Public Library to establish branches in the suburbs; instead, there was a system of subsidies available for community organisations which chose to provide library services for local people. Many organisations took up the challenge, including the Linwood Citizens’ Association, which was established in 1908-9 under the leadership of Daniel Richardson (1854-1936), a local timber and coal merchant. Linwood Library, which, according to its historian, Arthur Brettell, was one of the Association’s “best accomplishments” 1, was destined to be amongst the largest and most successful of the voluntary libraries which developed around the city in this period.

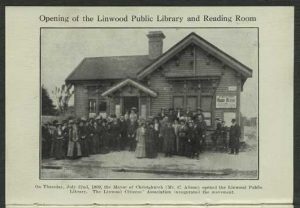

Arrangements for the establishment of the library were quickly put in place during the first months of 1909. In March, the Association’s secretary, Henry McMillan Chappell, secured the lease of the old Linwood Borough Council building on the corner of Stanmore and Worcester Streets from the Christchurch City Council, at a rental of 10 shilling per annum. This timber building had been designed by well-known Christchurch architect, Joseph Clarkson Maddison (1850-1923), and erected at a cost of 289 pounds in 1885 by G. S. Dale and Company as premises for the Linwood Borough Council. The building was available because the Linwood borough had been absorbed into Christchurch City in 1903. It featured return gables, twin entries, sash windows, and coloured, geometrically patterned fanlights, reflecting Maddison’s classic stylistic conventions, and restraint and economy of design. Having secured suitable premises, a public meeting was held on 30 April “to establish a public library in Linwood”. The library’s stated goals were to improve public utilities in the suburb, and to safeguard and enhance general civic welfare. In May, a constitution and by-laws were drafted, and the subscription fee set at 5 shillings per annum. For this price, each subscriber could borrow one book per week. On 15 June, officers were elected, with local bootmaker, unionist and Labour MP, William Wilcox Tanner (1851-1939) as president, and a committee of 12 officers. The Christchurch City Council granted 40 pounds for set-up costs, and the Books Committee was allocated 25 pounds to buy books. When the library was formally opened on 22 July by the mayor, Charles Allison (1845-1920), the shelves were stocked with 960 books (many were donations), and between 40 and 50 subscribers had joined. At first the library opened on three evenings a week but by December 1909, demand was such that it was decided to open every week night. Later, afternoon sessions were added, with women committee members assisting on Monday, Wednesday and Saturday afternoons.

In his opening address to the first public meeting held about the library, Charles Allison exhorted those in authority to use “…the utmost vigilance in order to prevent anything in the shape of pernicious literature creeping in…” 2. The Library’s promoters were determined to develop a collection featuring all the most worthy books available, including a selection of magazines, essays, history, biography and scientific works, as well as a wide range of fiction. Because they wanted to focus their energies solely on the social benefits offered by books and reading, they decided against establishing other social attractions, such as billiards, cards and evening entertainments, which were a major source of funds for some of the other voluntary libraries. Instead, Linwood instituted a charge of 3d per volume for every additional book borrowed above the one a week allocated free to each subscriber. This proved a successful financial decision; in future years, money gathered from this source (it amounted to well over 300 pounds per annum by the late 1920s) enabled the library to buy many extra books and also to make other improvements.

By 1929, Linwood Library was, according to its annual report, the “most flourishing institution of its kind in Christchurch” 3, and the only library to earn the full subsidy of 100 pounds per annum offered by the City Council (increased to 125 pounds by the 1940s) 4. There were nearly 1800 subscribers and over 20,000 volumes available to be borrowed, of which around 3000 volumes were non-fiction. The average number of items borrowed each day was 368, magazines and newspapers were well used, and the juvenile department, inaugurated in 1923 by Mr Reynolds in the hope of directing youth away from the distractions offered by “picture shows” and other entertainments 5, was also well patronised. The library’s long-time book buyer, Alfred Marshall (1859-1936), manager of the Mutual Benefit Building Society in Christchurch, had been able to spend over 600 pounds on building the collection during the year. Both the mayor and Councillor Dan Sullivan noted at the annual general meeting that extensions or even a new building would clearly soon be needed, and offered their “enthusiastic support” for such an enterprise 6.

Needless to say, the Depression of the following years soon put an end to any building development plans. When the Library launched its monthly Linwood Library gazette in October 1935, to

establish a link between subscribers and the management committee, there were complaints about the small, crowded rooms, and the lack of proper facilities for juvenile readers and others. The Library regretted that increased subscription costs would be needed to offset the growing cost of books, although at the time of the Library’s 50th anniversary in 1959, the annual subscription was still only 7 shillings, an increase of 2 shillings in 50 years. Nevertheless, within the limited resources available, the Library’s book buyers were determined to maintain the quality of the works offered to subscribers, and to avoid the stigma of being labelled “a collection of novels” 7. The management committee was proud of its non-fiction collection, frequentl

y urging “inveterate” fiction readers to devote themselves to more “educational and informative literature”, some of which was “far more thrilling” than adventure stories, and provided “lasting memories” and a broader outlook on life8. They were delighted when T.E. Lawrence’s Seven Pillars of Wisdom proved so popular that two additional copies, a reduced borrowing period and an 18-month long waiting list became necessary 9. Travel books and biographies were the most popular non-fiction genre but the library also stocked books on New Zealand and Māori history (this collection was finally handed over to the Public Library in 1972, where the committee hoped it would be better used). Fiction by New Zealand authors was another feature of the collection, with a particular focus on Canterbury writers such as Ngaio Marsh, Edith Howes, Mona Tracy, Jessie Mackay, Norman Berrow, and others. Juvenile books were “carefully chosen” to encourage young minds into a love for “deeper and more serious subjects and affairs” 10. Committee members were forced to acknowledge, however, that, although it was important to develop the non-fiction section, “most – nearly all in fact – of our subscribers are purely fiction readers”, and that most money therefore had to spent in this area11.Despite the committee’s best efforts, membership began to fall off during the 1930s; by 1939 there were fewer than 1400 subscribers and the annual report noted that “with greater spending power, the public is seeking amusements in directions other than reading” 12. In order to increase patronage, the Library introduced an alternative membership scheme in 1941, which enabled borrowers to use the library along commercial book club principles. This scheme was successful in attracting some new members 13, but adult membership hovered at under 1000 throughout the 1950s, and dropped to under 600 in the 1960s. The opening of a free children’s library service in 1954 was, however, very popular, with nearly 2000 children, aged 4-16, enrolled by 1958. This service was supported by Council rates through the Public Library, with books being purchased from a special fund. The children’s library, which was decorated in chocolate brown, grey and bright maize yellow, was staffed by volunteers from among local school teachers and parents, and was open after school hours on Monday, Tuesday, Thursday and Friday afternoons 14.

Problems began to compound in the 1960s, with the impact of television causing membership to fall among both adult and juvenile subscribers. Linwood’s 1972

annual report noted that the children’s section had halved over the previous two years. In 1969, yet another form of membership was introduced for adult borrowers: they could remain as subscribers or could join under a new free and rental system, paying for some books and borrowing others for free from the collections known as the “K” pool, supplied by Canterbury Public Library. The Public Library also offered a request service, similar to today’s interloan service, whereby Linwood subscribers could request books not held in the Linwood collection. The biggest problems faced by voluntary libraries in this period, however, were the declining numbers of volunteer staff and the loss of books. The “privilege of free and cheap reading is being abused”, stated the 1972 annual report, adding that magazines were constantly being stolen or mutilated, and books treated as “free game”. Linwood had by this time become a flatting area, with a large, mobile population, and many borrowers failed to return their books before moving out of the suburb. In 1974, all newspaper subscriptions were cancelled, although the introduction of large-print books the same year proved popular.

Even more problematic was staffing. As women returned to the work force during the 1960s, it proved harder and harder to find either committee members or volunteers for the adult and children’s libraries, both having to depend more and more on their “stalwarts”. Saturday hours ended in 1969 because no volunteers could be found, and in 1975, evening hours were reduced during the week for the same reason. Women were not prepared to work at night, noted the annual report, and men were not interested. The children’s library had only two assistants in 1973, and the committee said it would have to close if more parents and teachers did not come forward.

It had long been clear to Canterbury Public Library’s senior managers that the voluntary system of suburban libraries was no longer able to meet the demand for professional library services from modern borrowers around the city. As early as the 1930s, there had been considerable debate in the press about the pros and cons of a centralised library service in the city. Unlike many of the voluntary library committees, Linwood Library supported the idea of library reform. The Gazette editorial in September 1936 declared that “co-ordinating our several library systems into a single one, with central control, the necessary funds to be provided for by a special rate, is a thing to be desired…”, and the following month, president Arthur Brettell added that suburban libraries should lose their local and parochial outlook about such a service, which would eliminate financial worries and greatly increase the public’s access to the full range of published material and reference services. Such a professional service could only work for social good and to the benefit of local communities. Voluntary staff would also benefit from a close association with professional librarians and would learn more efficient methods of administration, while centralised purchasing and cataloguing systems would greatly reduce the cost of getting books onto the shelves. No other city of 120,000 citizens, the Gazette declared in August 1938, would tolerate the wasted money and effort of a library system with so many independent libraries, entirely lacking co-ordination, cohesion and systematic planning; changes were both urgent and vital. Linwood committee members demonstrated their “broad outlook” on libraries by taking an active part in both the New Zealand Library Association (at least 3 committee members attended each annual conference) and the Canterbury branch, which was established in the 1930s. In 1937, Brettell was elected as branch president.

The changes urged by Linwood in the 1930s were a long time in coming. Canterbury Public Library was not taken over by the city council until 1948, when library services were for the first time fully funded from rates. Although the Public Library gradually increased its subsidies to voluntary libraries, including free children’s services in the 1950s and some free adult collections in the late 1960s, the first suburban branch library was not opened until 1971 (in Spreydon). Other branches followed in quick succession during the 1970s and 1980s (New Brighton, Papanui, Bishopdale and Shirley among others), but, as chief librarian Dorothea Brown noted in 1992, although a Linwood branch had been discussed as early as 1967, the eastern side of the city remained a blank spot on the library map, and nearly a quarter of the city had no easy access to professional library facilities 15. It was not until November 1993 that Linwood Public Library was finally opened in the new Eastgate shopping mall. The once flourishing voluntary library had by then become a very small and struggling shadow of its former self, yet for over eighty years had provided a valued and valuable community facility through countless hours of dedicated voluntary service. The building vacated by the library remained in Council ownership and was refurbished in 1997 as a community-based facility, Te Whare Roimata, for the performing arts.

Related pages

- A brief history of Christchurch City Libraries

- Christchurch Mechanics' Institute

- 150 Years - celebrating Christchurch City Libraries

Sources

- Brettell, A. A record of the foundation and early period of the Linwood Public Library, Linwood Public Library Committee, 1928

- Canterbury Public Library. Newspaper clipping books, 1913-1951, Arch. 52, Christchurch City Libraries

- Linwood Library gazette, 1935-1938

- Linwood Public Library. Records, Arch. 107, Christchurch City Libraries

- May, J. “An open book on an old library”, Press, 28 June 1997, p. 14

- Press, 1954-1994

Footnotes

1. Brettell, A. A record of the foundation and early period of the Linwood Public Library, Linwood Public Library Committee, 1928, p. 1

2. Press, 28 June, 1997, p. 14

3. Sun, 26 June 1929

4. Press, 27 June 1923, Star-Sun, 11 March 1941

5. Press, 27 June 1923

6. Sun, 26 June 1929

7. Gazette, v.2, no. 1, October 1936, p. 2

8. Linwood Library gazette, v.1, no. 3, December 1935, pp. 4-5

9. Gazette, Nov. 1935, Jan. 1936, Nov. 1936, July 1937

10. Gazette, v.1, no.1, January 1936, p. 7

11. Gazette, v.2, no.1, Oct. 1936, p. 2; v.3, no.9, July 1938

12. Press, 8 March 1939

13. Star-Sun, 11 March 1941

14. Press, 26 October 1954, p. 6, and 2 May 1958, p. 7

15. Press, 14 Feb. 1992, p. 5