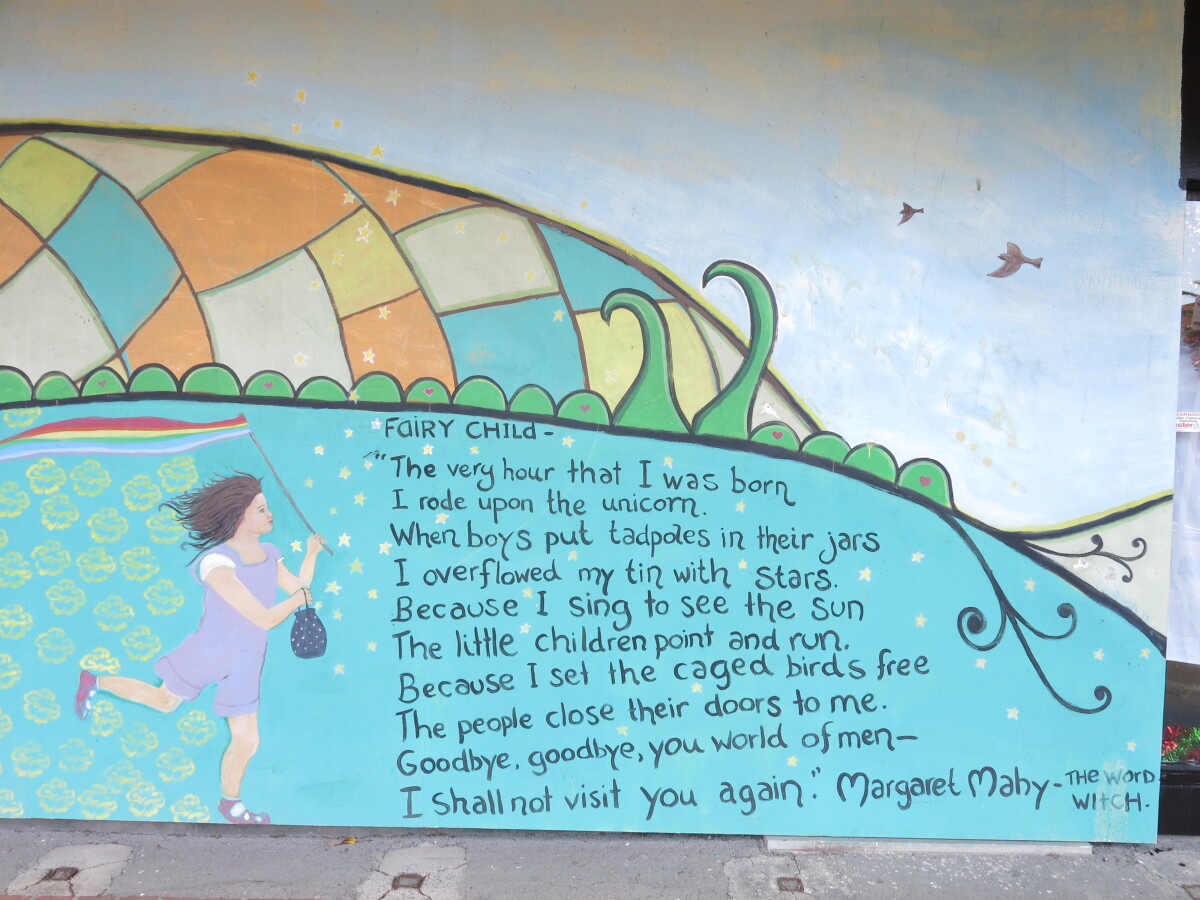

Margaret Mahy - In her own words

Margaret Mahy is famous for writing numerous award winning books for both children and young adults but have you ever wondered how she was able to create such wonderfully evocative characters and detailed worlds? Read on to find out!

Ideas

Many stories, regardless of length, spring from a single image which makes connections with other current images or with images in memory.

I sometimes tell people about the initial incident, but seldom say that I am thinking of writing a story about it. Sometimes telling people is just one of the ways of helping myself to make up my mind about whether or not this is actually going to turn into a story. I want to hear what it sounds like.

My ideas mostly come from things that happen to me, but of course they are changed a great deal by the time the story is finished. The ideas begin with real things but I invent all sorts of things to add to them, or I change them in some way before the story is finished.

Research

I seldom do a story that requires a great deal of research, but when I do, I do it more or less at the same time that I write, and I also read books and listen to music that helps me to maintain a particular mood.

As I have a very large number of books, most research I need to do is around me, but on occasions I have rung the police, the coroner’s office, the St John’s Ambulance Service and, of course, the library, looking for details which will add a bit of verisimilitude to my stories.

Characters

When I have an idea properly established I think of it all the time… driving, gardening, shopping… sometimes the story becomes so interesting to me that real life becomes rather shadowy for a while. In effect I have to abandon my own life to let the life of the story take over.

I think hard about the characters, partly inventing them, but also using pieces of many people I know. Apart from Sophie in Memory I don’t think I have ever based a character on any one I know, but I use incidents from my own life all the time. They seem to fit with fictional lives very well. I think most of the stories I write are suggested by some sort of incident and this, in turn, suggests the characters who might be involved.

Audience

I don’t ask children what stories they like or want. I think I have a good memory of the sort of stories I enjoyed, and in the beginning I am writing for the sort of listener I was when I was a child. In the beginning the author is not only the writer of the story, but the reader too. I don’t brainstorm with anyone else except myself.

First drafts

I almost never get stories right at first draft stage unless they are very short indeed. I don’t worry about spelling, grammar or punctuation, although I think it is important to know about all these things since without them a story becomes too difficult to follow, and there is no sense in writing a story in which the reader will be continually hesitating, wondering just what is going on. I correct a lot of mistakes I make at a later stage.

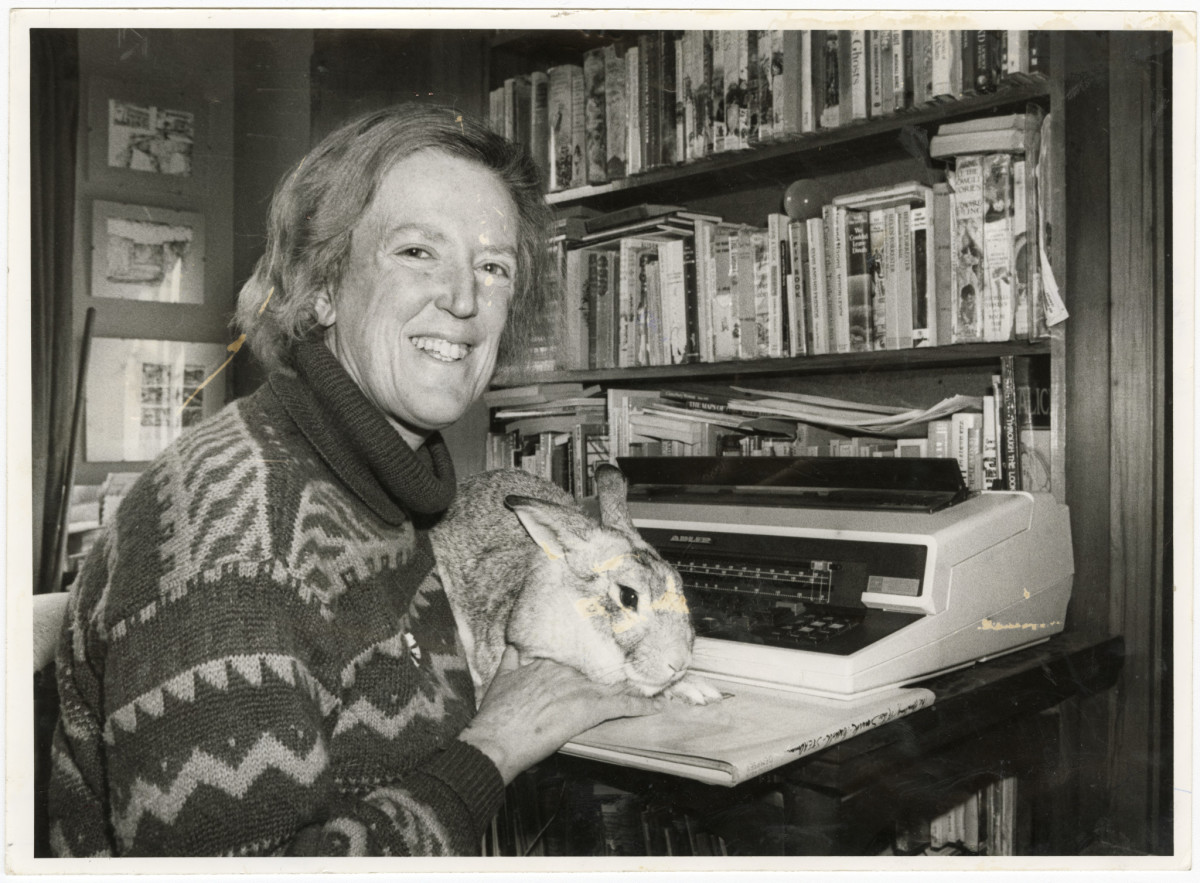

I sit down at my word processor and begin work, get something down and then leave it for twenty four hours. If I am working in long hand, I write on every second line so that there will be room for corrections which I do in ink of a contrasting colour, so that scribbles and tiny printing will be easier to read.

I write best in or around my home, and I think I write best during the day, though for many years I used to write late at night, sometimes all night. However I am older now and get tired more easily, and, being a full time writer I have time during the day.

I alternate between working on the screen and on the page (with pen or pencil) but find I work a little differently on the page from the way I work on the screen, so I try to do both. In some ways I think the best editing is done on paper. The screen presents one with a constantly clear version which can be wonderful, but paper enables one to see simultaneously where one is, and where one has been. It is often very hard because of the collapse of judgement as one writes and revises, but every now and then it goes wonderfully well, and that is both exciting and a great relief too.

I keep notes as I write novels, since I am going to have to bring early chapters in line with later ones, both in terms of action and in terms of metaphor too. I have a piece of paper beside my word processor and scribble notes down as I go.

I try to get started by 9am each day, and ideally, I should begin by going over what I did the day before. I often find I improve yesterday’s work a great deal and get new ideas that spring fairly naturally from the basic form laid down the day before. If the ideas don’t come I go for a walk, listen to music, do a bit of gardening, but I have so much work, it is always easy to go onto something else for a while. If it is urgent I make something happen, even if I am not particularly satisfied with the level of invention, because I think as long as the story is moving something is going to happen, and so far I have been lucky. The inferior (or place-holding) ideas are discarded when something better comes along.

Often, as I write, the end of the story changes, or characters change, and thought I often have the end in mind, it always winds up by being a little different from what I had originally envisaged. I have sometimes written the end of a story before I have written the middle of it, partly hoping that the end will define the middle, as it sometimes does.

A really short story (and my shortest story is about nine words long) may only take a little time out of every day for a week or so. There is less work involved in writing, typing, correcting, and the pattern is more easily grasped. Novels take me anything from six to eighteen months.

I sometimes find it very difficult to get a title, and I am not entirely satisfied with some of the titles I have. I want the title to show, fairly clearly, just what sort of book this is and who it is intended for. With The Changeover I gave the book a subtitle

a supernatural romanceso that people would be warned.I do abandon stories that are not working out, but I don't forget them. Often I go back to them in later years, sometimes successfully.

Revising

I always revise, and often do at least four drafts of a story, sometimes more. While revising, I think about the way the story flows (how smoothly and at what pace) and try to think about the way it sounds, even if it is a long story which might not ever be read aloud. I do use a thesaurus and a dictionary as I work, very frequently in the middle of the revision process, but much less as I get towards completion.

I have literally thousands of books in my house and I usually have all that I need around me if I need to check on any facts. The ones I use most are scientific ones, but I also find myself looking at history too.

I always write too much to begin with and, sometimes, as I revise I make the language too elaborate and have to simplify again at a later date. That is where reading the story aloud is always a help.

I make the changes on my manuscript, then go to the word processor and put them in on the screen text. I do correct onto the screen at times, but I think the best editing is often done on the page first. It is always a good idea to put a story aside for a little time before correcting it. Sometimes overnight is enough but, after the story is finished, I think one should probably put it aside for a month, and then revise again. One’s judgement is usually restored by the break, and once can correct more incisively.

The second draft is usually better than the first, but parts of it are sometimes not as good. There is always a tendency to make things unnecessarily complex and to think one is improving things, when all one is doing is trying things out, and maybe improving one’s own view of the story in a way that should, in the end, be implicit, rather than explicit. I sometimes do become bored with a story at a second draft stage, but usually with stories that someone has commissioned me to do, rather than with stories I have thought up myself. I find writing for television hard in this way.

Illustrations

My novels are not illustrated, except for the picture on the cover. Everything I write is intended to be ‘heard’ in some way or another. The sound of the story is the illustration I write into it.

With the picture books the publisher chooses the illustrator and though I am consulted I have very little to do with the illustration.

I occasionally am consulted, but the artist is the artist and is entitled to work with his or her own ideas. If I have done my work well the artist won’t be too far wrong (unless, as sometimes has happened, he or she tries to alter the central images of the story because of what they want to draw.) The artist never conveys exactly what I had in mind but sometimes the illustrations are very enlightening for me and I adjust my ideas to encompass those of the artist.

I quite like it when the artist tells his or her story in the illustrations provided it does not distort the text. There is a lot in the illustrations of The boy who was followed home, for example, which is not referred to in the story, but the pictures are true to the story all the same and I think it is a successful book.

Editors

A good editor can take the place of passing time, can read with fresh judgement and be of great help, particularly towards the end of the process, which is usually when they come in. I hope for an editor who has better mechanical skills than I have, more business contacts and acumen, and whose judgement, while it may more or less parallel my own, will be more incisive and constructive at the final stage of the story.

Much editorial comment on my stories is concerned with the fact that I tend to make things too long. The editor also picks out incoherencies of various kinds, both verbal and in terms of the action of the plot. I suppose one is always upset at some level by criticism, but it is essential and, at times, can even be welcome because the editor has seen a way to improve things in a way that you, as author, have been unable to see.

In the end, all kinds of writing, except the secret diary sort, are intended to be read and talked about. That is part of communication. The skill of author and editor is knowing when and what sort of comment is appropriate.

No-one reads my manuscript until it goes to the editor. I read aloud to my daughter. The editor and other readers are the first people to see it. In the end perhaps four or five people have seen it before it is published.

Publication

I suppose it takes about a year for a book to be published… more if one has to wait for an illustrator to make room for it in his or her work programme. Initially I write for myself but in the process of editing I do keep a particular audience in mind. I want my book to be published and read, and I am aware of the sort of reader, and the age of the reader from early in the writing process.

I am never quite satisfied with any finished book, though I still take a lot of pleasure in them. By the time any book is published I am usually deeply involved with another story, and I don’t worry too much about the imperfections in earlier books.

Reviews

I read the reviews with a great deal of anxiety, because I believe them, even though I know how relative all such opinions are. Some I value more than others because, having been a librarian, I know that some are read by people who are wondering whether or not to buy a particular book. I am also sufficiently snobbish in a literary way to get pleasure from good reviews in ‘literary’ journals.

In some ways this is all a little bit of a literary game which, since I often get good reviews, I quite enjoy playing. However I know that there are many good books that are well reviewed and impeccable from a literary point of view which have left me unmoved, and other, much more perfect books which I have loved.

The relationship with a book and a reader is personal and unique and often illogical. Reviewing is useful in many ways, but it does not necessarily affect that relationship.

Readers’ letters

I get a lot of letters from schools, many of which have been stimulated by a language programme. Some children write without prompting however. I try to answer them all, but I am often late with them. Even with a word processor, it takes a long time, and sometimes, where is school project is concerned, there are many questions. Some people are very unreasonable in what they expect. All the same I try to answer their letters.

Some people have said that they hated my books, usually because of the supernatural elements in them. What can one say? I am sorry and feel a bit guilty because I want people to enjoy reading what I write, but I also want the freedom as a reader to dislike certain books written with every bit as much sincerity as mine. People like different books and so they should.