I've been waiting to see Patricia Grace (Ngāti Toa, Ngāti Raukawa and Te Āti Awa) in person for a long time. Maybe a lifetime.

I've been waiting to see Patricia Grace (Ngāti Toa, Ngāti Raukawa and Te Āti Awa) in person for a long time. Maybe a lifetime.

So I was excited and a little overwhelmed when she took the stage at the Christchurch Town Hall for WORD Christchurch Festival.

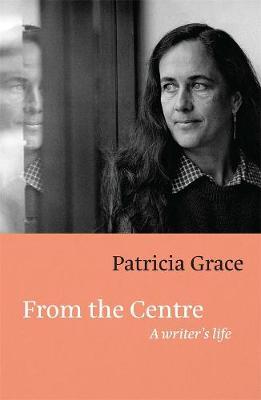

Patricia was interviewed by WORD Programme Co-director (and fellow writer) Nic Low (Ngāi Tahu), who asked her about her recent memoir, From the Centre: A Writer's Life.

Where did the idea for her memoir come from?

Her publishers, says Grace. It was a timely idea, but she wasn't quite sure where to start. So she started with her grandparents and parents, finding that to focus on herself was 'not so comfortable'.

Central to that story was her beloved Hongoeka, a small community north of Plimmerton.

It's the setting for Potiki, and set the tone for many more stories where the marae and land are in contrast with living in the city.

As a child, said Grace, Hongoeka was a safe place. When living in Te Whanganui-a-Tara (Wellington), she visited every weekend, lived there for a time, and lives there now. Hongoeka's landscape was inviting, especially for a child. Her interest was held investigating the stony shore and the sea, and the bush, with its creeks. There were many cousins to play with and this play was enveloped by the loved and care of for by aunts and uncles.

When she stayed there, recalls Grace, she didn't miss her parents. Hongoeka was ancestral land: everyone was related or married to a relative of hers. "Living with relations is not for everyone," she laughs, having its challenges, but she will never be alone...

Grace takes a moment to remember her ancestors: "Some have gone ahead of me on that road…"

So it makes sense, then, that Grace begins with Hongoeka.

"Is that the centre?" asks Low

In answer, Grace quotes from the opening lines of Potiki:

From the centre,

From the nothing,

Of not seen,

Of not heard,

There comes

A shifting,

A stirring,

And a creeping forward,

There comes

A standing,

A springing,

To an outer circle,

There comes

An intake

Of breath –

Tihe Mauri Ora.

'From the centre' is also a fair description of Patricia Grace's writing approach. Setting herself and her characters in the middle, not knowing what's going to happen, she 'moves (the story) around' :

"I decided to sit myself in the middle of the story and move it back and forth around me. I found this to be a way that works for me – placing myself at the centre, keeping characters and ideas close, and from the centre reaching to the outer circles, in any direction, for what I need in order to bring everything together."

Her first book, Mutuwhenua, a story of a woman who leaves tradition and moves to the city to marry a Pākehā schoolteacher; was very linear. Grace carries on these themes, though subsequent writing was in more of a 'spiral fashion'.

Her first book, Mutuwhenua, a story of a woman who leaves tradition and moves to the city to marry a Pākehā schoolteacher; was very linear. Grace carries on these themes, though subsequent writing was in more of a 'spiral fashion'.

Low asks about Grace's Grandmother. The silent one. She was a great influence, says Grace, there were never any discussions but she was warm, kind and caring, although she never said much. Grace says she is the opposite: talkative and inebriated (with life)! What then, did Grace inherit from her? Her feet, she says. When doing yoga, in Kotuku, "I borrow her foot."

Grace speaks of her parents: her mum was Pākehā, her father Māori. Married before the Second World War, when acceptance of mixed marriage was not widespread, they found it hard to find somewhere to live. They had to live separately for many years, and the family was often shunned.

Grace recalls her father digging their home section out of the Wellington cliffs at Melrose (with a pick and wheelbarrow!) while the local kids would do a mock haka. He laughed it off, but the young Patricia didn’t think it was funny. She describes how once he stamped his feet, pretending to chase them. "One boy wet himself, one boy fell over," she laughs. We all laugh at that.

Despite the differences in culture, Grace's parents found a common point, and laughed together. They both loved children, and family. Grace remembers being discriminated against; the only Māori child in Melrose, accused of all sorts of things: teaching kids to swear, stealing a gun, "But I was a goody two-shoes really."

Nic asks, "How important is whānau who support what you do?"

Grace responds that some are here today… But the greatest support of all was that of her late husband, Kerehi (Dick) Waiariki Grace, who left her space to do what she did, and encouraged her to be a full time writer.

Grace has never been one to lock herself away. She was often writing by hand, and needed quiet time to type that up, "but you still need to be among people". Low suggests this is a kind of 'anti-residency'. Grace responds with "all interruptions gratefully received…"

Was there a sense of writing for whānau? "I think it was my main aim."

"Character is the most important thing for me. Ideas, themes, voices, dialogue, background all belong to that (main) character. I have faith the story will come about if you're true to your character."

Was there a time when Patricia Grace's characters weren't accepted in writing?

To give herself context, Grace looks back to her early school life, full of English books with characters who didn't fit into this landscape:

Children were told to write about a day at the 'seaside', or in the 'forest'. Grace didn't equate this with the bush, and 'no one said the seaside is really the beach'. Woods, woodcutters and wolves, brooks, bluebells, stripey tents where people changed into their bathing costumes all came out in her early writing.

In her teens she read 'English men who were already dead' (I felt this too, at university).

At university, however, she began to read New Zealand authors and settings; Katherine Mansfield, Frank Sargeson and Māori writer J.C. (Jacqueline) Sturm.

Grace reads from her memoir: how, when meeting Frank Sargeson and his wife, she realized that daily life and relationships could be written about and related to.

"This was a setting living in its own time; people writing about what's close at hand, from the self."

As a girl, Grace says te ao Māori was kept for Tikanga and Tangihanga. Grown ups didn't speak it in front of her. Her husband was punished for it. Of her stories, she says:

"I haven’t avoided the hard stuff, but I write about functional families, functional marae…I don’t know the other experience."

Patricia Grace talked about how she always felt safe on her ancestral land: "I write about functional marae, functional families, functional communities." @NicLow1 @WORDChCh #WORDChch pic.twitter.com/RKXItPOyec

— Elizabeth Heritage (@e_heritage) November 12, 2021

Grace says of Potiki "There was "a good reception mostly but it rocked the boat!" There were negative reviews, "I was trying to upset racial harmony...distancing the readers…that has changed, Potiki has made its way in the world and is probably better received now…"

Was Mata based on someone real, taken away from the family? Yes, but characters are always an amalgam of people.

Commenting on the current generation of Māori writers, Grace sees progress and acceptance, noting, "No one complains about Te Reo or other mother tongues in context now."

What did teaching bring to her writing?

It gave her subject matter but also kept her in touch with people, parents; "what's going on."

"I thought I would have all this time to write: time was the thing that I was short of. You can write all day every day but then you're not living a life... so I involved myself in other things as well."

Underestimated as a learner, because she was Māori, Grace knew that you could start "undervaluing yourself, believing people." Constantly having to prove herself to new teachers, as a teacher herself she strongly believed that each person coming through the door has ability.

When faced with the same foreign teaching resources, that didn't relate to them, Grace and Waiariki taught the children dance, drama, and art, to build vocabulary, "and we made our own books…"

Her advice for teachers?

In the revitalization of Te Reo Māori, especially for those separated from their tikanga,

"Seek understanding of one another and our cultures."

Nic Lowe acknowledges Grace's husband, Waiariki (Dick): Patricia says her book wouldn’t have been her story without his.

She and her husband were quietly fierce people, who responded to a need to change things from the inside. Grace illustrates this quiet strength when telling of the road, and again when she says she refused to have a glossary – which is for foreign languages – in Potiki. "We couldn’t call Te Reo a foreign language in its own country..."

Which brings us back to Hongoeka. Patricia lists the times and Dick stood with their iwi to protect it from: a coal fired power station in the nineteen fifties and sixties, a marina, a container port, turning the private road into a public road. "They wanted to develop land we were living on…" Discussions for these often had reached an advanced stage before Hongoeka people were approached. So they built a Wharenui there; "It's like a statement!" Although there are still efforts to make a public walkway there...

Grace also fought the Kapiti Expressway in Waikanae. Her Tupuna, Wiremu (Wi) Parata Te Kākākura (Ngāti Toa and Te Āti Awa), born on Kapiti Island, had already given heaps of land to the crown for the railway and such. This was the only bit left. Grace's approach? To keep saying no to NZTA and see what would happen. What happened were two court cases: one in the Māori Land Court, one in the Environmental Court. She won.

"Setting legal precedents as well as writing amazing books"

comments Nic Low, observing that there is some great stuff beyond Grace's writing: the fight for the land, standing up for what you believe in.

@WORDChCh Patricia Grace -

Ngāti Toa, Ngāti Raukawa & Te Āti Awa, talking about authenticity & accurately recalling her experiences. Full of praise for her book editor Harriet Allan "Good editors are like gold" pic.twitter.com/lmMpONyNph— Carol Bartle (@c_bartle) November 12, 2021

Is there a difference between writing and activism? "Not really," says Grace, "it’s a no brainer."

Will Patricia Grace's stories be translated into Te Reo? Potiki and Tu are the first, and there are plans to translate the rest of her work.

"Have you been true to yourself as a girl?" Grace asks of herself in From the Centre. "I’ve tried to,.. it's up to others perhaps to judge? ...am I still that person?"

Are you? Do you recognize yourself? "I think I do…"

I loved this session. Patricia Grace shared a lot of gems that aren't in the book. But her book is full of all our shared memories of her and more; an interesting account of a wonderful writer's life. It's well worth a read.

More

WORD Christchurch

- WORD Christchurch website (for the full programme and info about authors)

- Our coverage of WORD Christchurch Festival 2021 and WORD Christchurch

- Follow WORD on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram

Add a comment to: Quietly Fierce: Patricia Grace at WORD Christchurch Festival 2021