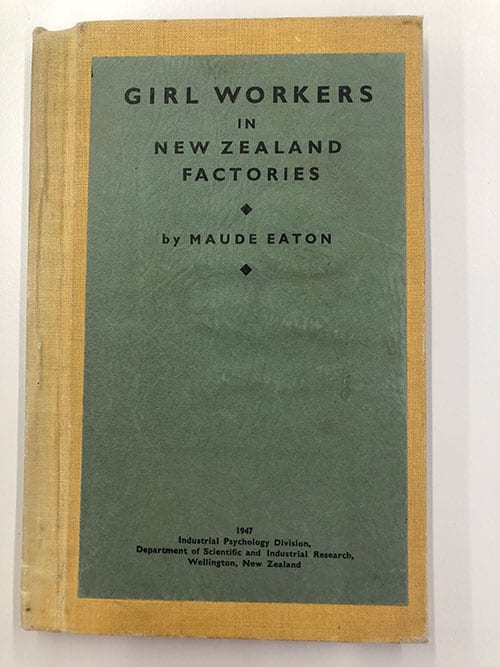

In 1947 the Industrial Psychology Division of the Department of Scientific and Industrial Research published a useful little report on the conditions of women factory workers entitled Girl Workers in New Zealand Factories.

The Industrial Psychology Division had been established in 1942 to help support the war effort by researching the working conditions of factories in wartime New Zealand. The first report of the Division was on industrial absenteeism, but with a massive growth in the numbers of women employed in factories (up to 35,000) other issues came under investigation.

Enter Maude Eaton, Dux of Rangi Ruru Girls’ School, recent graduate of Canterbury College, and keen investigator into the working conditions of factory girls. Maude interviewed over 400 “girls” in an attempt to identify and suggest solutions for “special problems” such as the effect of music on the performance of repetitive work, or the success of bonus schemes. Her observations were then published by the Division, but with a very cautious caveat in the preface noting that a number of the opinions and conclusions reflected her personal thoughts and that publication by the Division did not necessarily mean agreement with everything stated in the report.

Such as, presumably, the statement (remember this was written in the 1940s) that “shortages of labour are usually more acute among women than among men, if only because all men (apart from the very rich) have to work, while many women need to be directed, bullied, or begged.”

However, the favourable outcome of labour shortages (in Maude’s eyes) was that manufacturers were forced to compete for female workers, or girl factory workers, as Maude preferred to describe them, which meant they had to provide working conditions which would appeal to the workers. But because “factory girls are usually too unorganised and too timid to communicate their desires to manufacturers”, someone needed to step up and tell them, and that person was going to be Maude Eaton!

She has a few suggestions for the aspiring employer of factory girls. Modern workers/employers may want to take notes.

Cloakrooms – must be safe, with plenty of well-lit mirrors and washstands, and facilities for drying clothes. “Cloakrooms are undoubtably more important to a girl than to a man”.

Lighting – introduction of fluorescent lighting had the advantage of improving the workroom and assisting workers to see their work better, but some complained that it did not “enhance their physical appearance”.

Canteens – different approaches here. Some firms supplied everything, including soup for overtime shifts, or scones and cakes for tea breaks (provided at cost price), while others expected the girls to brew up for themselves. Provision of a good canteen saw an improvement in the girls’ health and vitality, and a reduced sickness rate.

Uniforms - preferably in clear light browns, pleasing greens, dark blues, and fitted to each individual girl. “Such uniforms are particularly pleasing if the colour is chosen with some regard to the predominate colours in the workroom”.

Music while you work – on no account attempt to raise the girls above their class by playing them classical music, even if the intensity of the opposition to this music is based on “fear and inferiority feelings”.

However, there are two behaviours that the employer must be on the watch for – “cloak-mongering” and, even worse, “lavatory-mongering”. You know, when the staff find any excuse to abandon the work area and abscond to the cloakroom or lavatory for minutes at a time.

Reactions to the report once published were somewhat underwhelming, and the section of the report on the response to the playing of classical music prompted a particularly condescending response from “Whim Wham” in The Press, with a little piece entitled “Psy no more, Ladies”, which must have made Maude writhe with impotent fury.

However, before the final publication in 1947, Maude was on her way to London and a post-graduate degree in Psychology at the London School of Economics and Political Science. She married a fellow New Zealander, William Geddes, in 1948, and then appears to have abandoned her academic career to accompany him around the world in his work as an anthropologist. Passenger lists for her trips list her occupation making a sad transition from the bold and confident “Psychologist” on her way to London from Christchurch in 1946, to “Lecturer”, then “Photographer”, and finally “Married” and “Housewife”. William Geddes took up a post lecturing at Auckland University College in 1951, but sadly Maude died five years later in 1956, just 35 years old.

In many ways Maude Eaton was ahead of her time, advocating for the rights of female factory workers, and making a number of important and sensible observations about working conditions. The key to her motivation is in the subtitle of her report “An Attempt to Understand Factory Girls and Their Problems With a View to Improving Their Conditions”.

And if you look past the occasional intellectual condescension, it’s more than a little disconcerting to recognise that many of Maude’s comments and suggestions still hold, and that there has not been a lot of progress in the lot of the female worker in New Zealand, particularly in the area of pay and gender equity.

A last little piece of advice from Maude: “it has to be remembered that complaints about temperatures are often a safety-valve for the ventilation of other grievances.”

Further information

- Eaton, Maude. Girl Workers in New Zealand Factories: an attempt to understand factory girls and their problems with a view to improving their conditions

- Hearnshaw, John. DSIR’s Industrial Psychology Division 1942–1954. Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand, Volume 47, Issue 2 (2017)

- Access treasures like this in our Research room / Wā Rangahau

Annette Williams | Family History Librarian

Tuakiri | Identity Team, Tūranga

Add a comment to: Give Factory Girls a Break!