1894 was a year when Christchurch was on fire with enthusiasm for a number of social and political causes – Temperance and its more extreme brother Prohibition, Licensing Regulation, Police Reform, Women’s Rights, Dress Reform, and Bicycling (possibly in the long run the most subversive of them all). And Mr Worthington was still delivering regular talks at the Temple of Truth (see The Worthington Lectures) not yet having fallen from grace over fraud and bigamy charges and departed for Melbourne.

Women were taking advantage of their new political awareness following the passing of the Electoral Act of 1893 which expanded the right to vote to women, but also highlighted the lack of rights for women in other spheres of life. One example was the right to participate in physical activities previously the preserve of men, with wide-reaching ramifications for what was socially acceptable behaviour and dress when engaged in these more physical pursuits. Cycling in particular was an exciting new recreation for young women, but came with many challenges, not the least that of managing multiple layers of heavy skirts, corsets, hat and sundry accessories while balancing on two wheels.

Bifurcated is Best!

Not surprisingly, aspiring women cyclists looked to the Rational Dress Movement in England for inspiration and solutions. Lady Harberton launched the Rational Dress Society in England in 1881, to (according to the report in the Otago Witness of 24 September 1881) promote the adoption, according to individual taste and convenience, of a style of dress based upon considerations of health, comfort, and beauty, and to deprecate constant changes of fashion, which cannot be recommended on any of these grounds.

“Rational Dress” initially consisted of variations on a basic scheme of a shortened skirt, worn over full trousers (so as not to reveal the true shape of the legs), or a “bifurcated” skirt which flowed uninterrupted to the knees before being divided into two separate leg coverings that gathered at the ankles. The trousers were often described as “Turkish trousers” and were not to be confused with the short-lived attempt by Amelia Bloomer in 1851 to introduce less restrictive clothing which promoted a “costume” consisting of full trousers and a much shorter skirt.

Some early adaptors of the new dress invented interesting variations of their own, using additions such as tapes, rings and even pulleys (think Roman blinds) to vary the length of the skirt in the course of daily activities. Many of these designs were patented, such as Mary Ward’s ‘Hyde Park Safety Skirt’. In the years between 1890 and 1900, 86 patents for cycling skirts were registered in Britain, including one from Charles Bristow of Wellington in 1897 for ‘A New or Improved Skirt Attachment for Lady Cyclists’.

Women in New Zealand could write to Lady Harberton in London to obtain a copy of a pattern to make their own “dual” or “divided” skirt, but it still took some years for the concept to filter through to the Antipodes.

Kate the Reformer

Kate Walker (also Catherine or Katrine) was one of the early advocates for the Rational Dress Movement in New Zealand. She was born on 19 April 1866 in Milton to Alexander and Isabella Walker, who had arrived in Otago from Scotland on the Orient in 1861. Kate won scholarships to Otago Girls’ High School and Otago University and became a teacher. An early teaching position was at Dorie School, in mid-Canterbury, which may be where she met her future husband James Reeve Wilkinson of Chertsey, also a teacher.

Kate and James developed a common interest in dress reform, co-writing a publication entitled Notes on Dress Reform And What It Implies, published in early 1893, and leading the Rational Dress Movement alongside Alice Burn. They argued that freeing the body from the heavy and cumbersome over-decorated modes of dress women were subjected to would also free them to take part in other aspects of life previously denied them.

"Unsuitable dress, we believe, is the chief cause preventing school girls, or such of them as are naturally active, from acquiring that physical vigour which, in the case of boys, enables them after leaving school to take a strong active part in what goes on around them. Girls, on leaving school, fall still more from physical activity by adopting long dresses, and by giving themselves more or less completely to domestic life."

This freedom of dress also included the women employed in domestic labour or factory work, not just the leisured classes who could afford to follow sporting pursuits. Kate and James were concerned with the rights of all women, regardless of class or wealth.

They were also keen cyclists.

Those photos of Alice

Initially advocacy for rational dress was included in the remit of the Canterbury Women’s Institute, formed in September 1892. One of the “departments” of the institute was the Health and Dress Department but within a year the dress reform champions had established so extreme a reputation in the eyes of the public that the rest of the Institute voted to dissociate themselves from their activities.

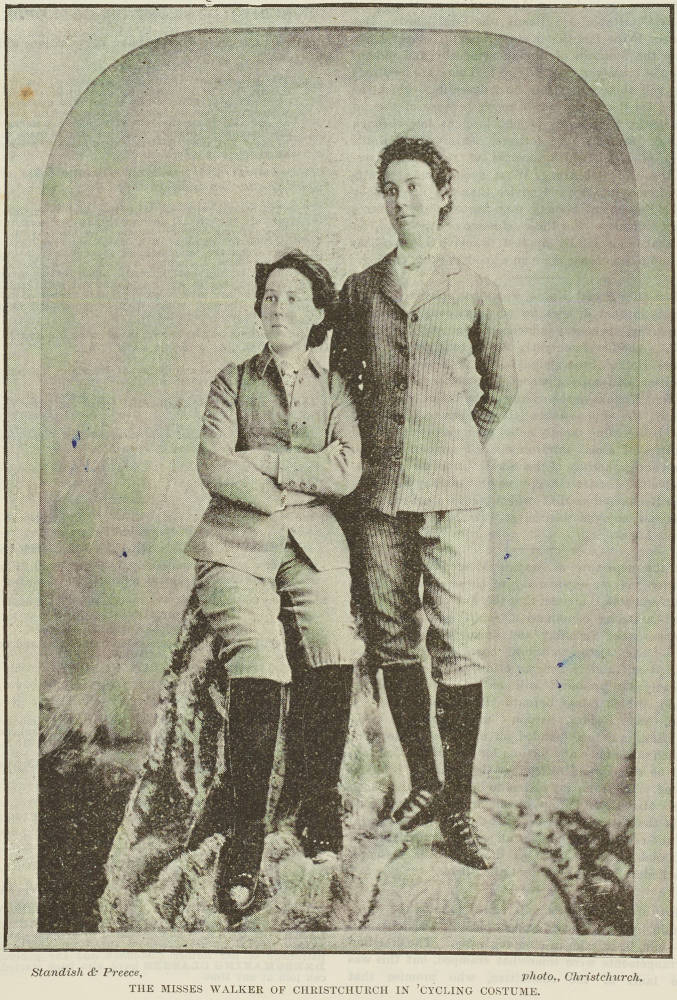

Stalwarts of the dress reform movement included Kate Walker, her sister Nelly, James Wilkinson, Alice Burn and her husband David. Some of their actions presumably contributed to the reputation as extremists.

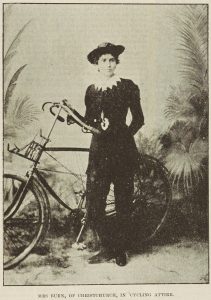

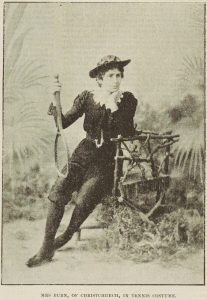

The Walker sisters in knickerbockers and an unnamed group of women cyclists similarly clad were photographed for the New Zealand Graphic and Ladies’ Journal issue published on 1 July 1893. Then Alice Burn was photographed wearing knickerbockers for cycling and tennis in the issue published two weeks later.

This was controversial enough, then Alice created a stir in the newspapers in April 1894 when she was refused admission to Canterbury College after applying for permission to wear knickerbockers to class - the attempt to storm that great institution of learning was apparently a step too far into the breeches.

A Rationally Bifurcated Wedding

Then Kate Walker and James Reeve Wilkinson got married. It was not an ordinary wedding. The ceremony took place on Saturday 13 March 1894 at the house of David and Alice Burn in Montreal Street and was conducted by the Reverend L. M. Isitt (a well-known Prohibitionist sympathetic to women’s dress reform), with witnesses James Millar Izett (fellow teacher and member of Worthington’s Temple of Truth) and Helen Walker (Kate’s sister, also known as Nelly). So far, so conventional, complete with bridal veil.

But when a photo of the bridal group was published in New Zealand Graphic and Ladies’ Journal, the story of the trousered wedding reverberated around New Zealand and beyond its shores. All members of the wedding party were dressed in breeches or knickerbockers, with vests and coats to complete the look. Lace and satin trims added a touch of femininity to the women’s outfits, all designed by Alice, but this made little difference to the vehement opinions expressed in the press.

The London correspondent of the Ashburton Guardian in the 19 November 1894 issue reported one of the responses:

“Genuine disgust was expressed by all true women with the publication in the London Sketch of the photograph of the “Rational Dress Wedding Party” taken in Christchurch, New Zealand, last summer. Thank Heaven we are a long way from brides in breeches!”

Moving on

Following the notoriety of Alice’s attempt to attend Canterbury College, and Kate’s wedding, moves to formally structure the Rational Dress Movement came in Christchurch on 14 May 1894 at a meeting in the rooms of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union when the New Zealand Rational Dress Association was formed. Alice was elected President, Kate Vice-president, and Eva Meredith Treasurer.

Response in the press was predictable, with correspondents questioning the decency of the new look and others defending it. One gentleman went so far in support as to upbraid members of his sex for giving more respect to the garment than the wearer, and also suggested that one outcome of the dress reform was that by encouraging a healthier and freer companionship of men and women it became a factor for moral good.

After the initial flurry of heated responses on both sides there appears to have been little ongoing commentary on dress reform. The Burns moved to Dunedin, and the Wilkinsons devoted themselves to teaching and other good works, and the movement quietly subsided.

However, as reported in the Star issue of 24 January 1929, thirty-three male shopkeepers and workers in Armagh Street, Christchurch signed a pledge to support a Summer Dress Reform League to free themselves from “the thraldom of conventional dress” and wear tennis shoes and “canoe” shirts and throw away their stiff collars and restrictive ties. Apparently, they wished to imitate the “free and more comfortable styles of the other sex”.

Happily ever after

Kate and James Wilkinson had one daughter, Kathleen Wave Wilkinson, born in June 1903. Kate continued teaching, taking up the role of school mistress at Bushside School near Alford Forest in mid-Canterbury in 1906. James retired from teaching because of poor health but was employed first as a clerk for Ashburton County Council, then by Ashley County Council. He was interested in silviculture, advocating for the planting of the Ashley state forest, and also encouraged the pupils at Kate’s schools to establish school gardens.

The Wilkinsons retired to Rangiora where Kate died in July 1941 aged 75. James lived until he was 94, dying on 27 April 1951.

In their respective obituaries there is no mention of their involvement in the Rational Dress Movement or their bifurcated wedding.

See also:

- New Zealand Rational Dress Association

- Alice M. Burn

- Atalanta Cycling Club

- Jungnickel, Katrina. Bikes and Bloomers: Victorian women inventors and their extraordinary cycle wear, Goldsmiths Press, London, 2018

- Regnault, Claire. Dressed: fashionable dress in Aotearoa New Zealand 1840-1910, Te Papa Press, Wellington, 2021

- Walker, Kate and James Wilkinson, Notes on Dress Reform and What it Implies, Simpson and Williams, Christchurch, 1893

Cycling and suffragists

- Take our Women's suffrage quiz

- More posts about suffragists

- Read our post, Alice Burn: A lady who bids defiance to custom & convention

- Our page on cycling

Add a comment to: The Great Divide: Kate Wilkinson and the movement for rational dress