One day I would like you to go to the places that I have been and to see the things that I have seen but without the nasty bits.

This is a statement of a father's wish for his son. Why does the father want his son to go to the places he has been? Has the son made the wish come true? Come to find out answers at an author talk during the Christchurch Heritage Festival 2023.

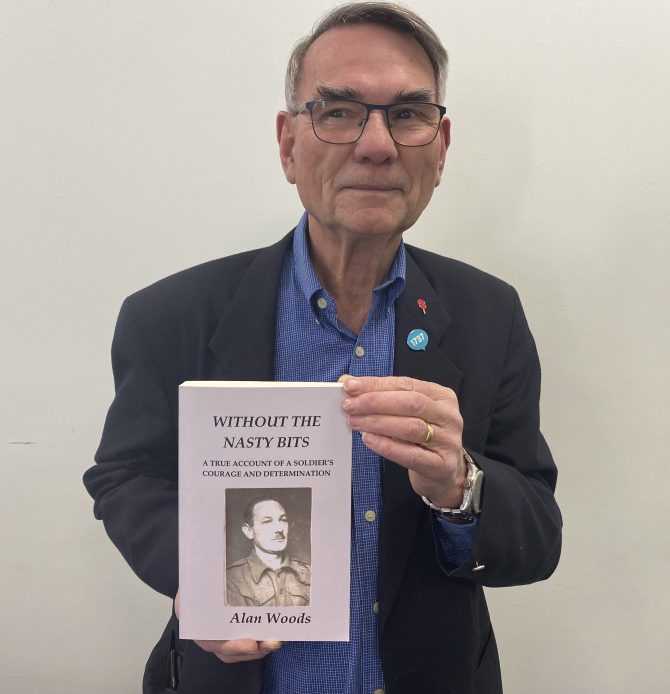

Alan Woods will give a talk related to his book entitled Without the Nasty Bits at Shirley Library on Saturday 7 October from 2pm to 4pm.

Without the Nasty Bits is a true story of a soldier's courage and determination. It weaves Norman Woods' experiences as a soldier and a prisoner during World War Two with Alan Woods' journey to Poland to follow in his father’s footsteps in 2018. In this way, this family memoir vividly brings the past to life.

Alan Woods, the author of this book, has been a Cantabrian for over 20 years. He grew up in Lawrence at his father's knee, hearing his stories from World War Two. Prompted by his father's words, Alan travelled to Poland in 2018 in search of the footsteps his father took in the remains of his final forced-labour POW camp near the town of Milowice. He returned to New Zealand to write Without the Nasty Bits. Alan is a father and a grandfather and lives in Burwood with his Bichon-Poodle dog. He is a volunteer in local community groups.

On Saturday 7 October, Alan is going to share his stories of the past related to this book and its writing process. His illustrated presentation will cover his family of origin and how this book came to be. The audience has an opportunity to learn about Alan Woods' journey, the research process for writing this book, data processing like the digital recording of an oral history using family narration, and even purchase a copy of the book onsite.

As a fan of books based on people's experiences in World War Two, I enjoyed reading Without the Nasty Bits and had mixed feelings of not only admiration for soldiers' courage but also grief for the damage and trauma caused by the War. While Alan was enthusiastically preparing for this event session, I had a chance to meet and ask him questions about the book and its writing process.

In this book, you talked about your twelve-year-old wish to go to the places your father has been. In 2018, you finally launched the trip. Why did you specifically choose that year to make your wish come true?

The year was not significant but the months of August/September were because they coincided with the invasion of Poland by German forces in 1939. Initially, I planned to travel in December/January because I wanted to be in Poland in winter but I was dissuaded by one of my guides – ‘You won’t like it here in winter Mr. Woods.’ January 1945 – winter – was when my father left Poland on the Long March and I wanted to get into the spirit of the event but that wasn’t to be.

From Chapter 10, you weave your experience in traveling to the places your father has been and your father’s narratives of his war experiences seamlessly. When you met local people on your trip, did you tell them the purpose of your travel? If so, what were their responses?

I took every opportunity to tell who I was and why I was in Poland. Many were surprised and questioned – wanting to know more. Telling my story opened opportunities for great two-way conversations. I like to think others learned more about their own country and mine. I certainly learned a lot more by telling as I went than I would have otherwise. It opened doors.

Your father's narrative of his experience as a prisoner is vivid and shows his resilience in the extreme situation. Did you refer to other historical materials when you edited this part? How did you verify what your father talked about the war and his war life?

Dad’s portion received little or no editing. I left it mostly as it was. When writing I gave him his own voice with a font of his own, and I changed nothing of his own words. I made no effort to correct anything he said and much of the factual material was able to be verified by the Official History – Wynne W. Mason. I took my father’s words to be a true factual and actual account of his personal experiences. It was, after all, his story of faith, courage, and determination – in his own words.

There are lots of valuable photos and images in this book. Would you like to tell me a little bit more about how you locate/find some of them?

Many of the photos were from Norman’s own collection. Some images were sourced in the public domain, some taken by myself, or others, and these I used with permission. On all occasions where I’ve reproduced photos, I’ve given credit. Some maps and diagrams I edited from open source material – like the Military District VIII on page 227 and the map of the Underground in Berlin on page 409.

I loved reading the part about your father’s post-war life when he returned home. You mentioned that your father did not receive special counselling for the trauma. How do you think he coped with his condition and how did your family help him recover?

How my father ‘coped’ after the war is pure speculation. He never spoke of any trauma or feelings of disappointment until he wrote his story. I believe several things played a part in his ‘recovery’: He came from a stable family background – his mother was a strong person and she raised him to be strong and resilient, he had lived a full and active life before the war and he stored every positive and negative experience for further reference later (he seldom made the same mistake twice), he was a person with Christian faith, he had an attitude of acceptance. All these things worked together for his good. Apart from that which the book records, what part his family or others played in his post-war recovery will never be known. For the most part, they were told not to talk to him about it and I believe they never did. If any conversations of this sort passed between Norman and Kathleen (his wife) we shall never know because neither of them ever spoke of it with others. He did talk to a few war buddies when he lived in Westport and like the stories he told children and other family members I believe these helped take the pressure off. The only in-depth conversation he ever had on the subject seems to have been the one he had with the psychologist when he applied for hearing aids for the 3rd or 4th time and then the advice was simple, ‘It’s the time your children knew your story, Mr. Woods’. If the family helped in any way at all I imagine was by being there and listening when he spoke, giving legitimacy to their father’s story. That said there were hidden depths within his mind that he kept to himself and these showed themselves in restless dream-ridden sleep in his later years.

This book is a personal story and family memoir. What message do you want to pass on to readers?

Take the story as written and as you read tread gently because you tread on one man’s dreams and experiences the likes of which we may never know again; please God. Remember Norman and speak his name for in doing so you keep his memory and thereby, the man, alive.

Do you have questions to ask Alan? If so, come along to his talk in Shirley Library at 2 pm on Saturday 7 October.

Thank you Alan Woods for answering interview questions and providing information used in this post.

Add a comment to: Without the Nasty Bits: Alan Woods – Christchurch Heritage Festival 2023