Since I was a callow fifth-former (Year 11 in the modern parlance) being taught English by the impassioned Brother Roger at Sacred Heart College in Glen Innes, Auckland, I have had a soft spot for the Romantic Poets. Seeing the incumbent Poet Laureate, David Eggleton, astride the stage like a poetic Colossus, I was put in mind of the opening two lines of John Keats' ode, "To Autumn": "Season of mists and mellow fruitfulness,/Close bosom-friend of the maturing sun;".

I lived in Auckland from 1983-1986 and I lived just a pleasant stroll away from the Globe Tavern in Wakefield Street which was the place every aspiring and established poet flocked to weekly on a Tuesday evening. Every week it hummed with young poets who sometimes railed against the cold shadow of neo-liberalism which was beginning to creep over the once-prosperous shores of Aotearoa. And among their number was a young David Eggleton whose unique style was being forged in a baptism of beer and cigarette smoke. His images came at you like a runaway train and his rapid-fire delivery put me in mind of a Beat poet on speed.

I freely admit that the poetic cauldron of the Globe Tavern did not bubble me up into the heady vapours of poetic fame, but many a literary career was started there. After all, where would the firmament of Aotearoa's literary stars be without such names as Riemke Ensing, Bob Orr, Iain Sharp, Stephanie Johnson, Sandra Bell (no relation), Michael Morrissey. Murray Edmond, Stephen Oliver, Fiona Kidman, Michael O'Leary, John Pule and Elizabeth Smither, to name but a few?

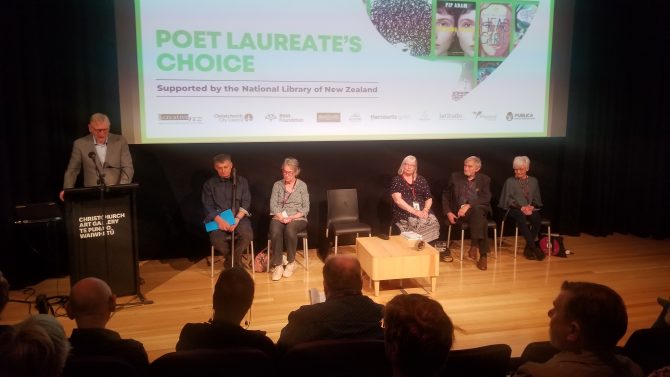

Fast forward nearly forty years and David Eggleton has now assumed the mantle of poetic elder statesman. And as the incumbent Poet Laureate of Aotearoa, Eggleton had invited five poets from Te Waipounamu to ponder the the question: "How might we find ourselves in the landscape?" These five poets were: Cilla McQueen, Kay McKenzie Cooke, James Norcliffe, Owen Marshall and Bernadette Hall.

In his introduction, Eggleton showed the audience the tokotoko, made by artist Jacob Scott, that had been presented to him when he became Poet Laureate. This tokotoko was carved from piece of maire and given the name, Te Kore. It was given this name because it had a hole near the top and Te Kore meant "the void of unlimited potential". Perhaps this void is the place from which all human creativity emanates.

Referring to the premise for which he had gathered his invitees, Eggleton said that the global Covid-19 situation had emphasised Aotearoa's natural borders, the Tasman Sea and the Pacific Ocean. Cloistered as we were from the worst ravages of the virus, New Zealanders were given a chance to turn inward and reassess their relationship to our landscape, how it shapes us and how we shape it.

Although originally from Auckland, Eggleton has lived in Ōtepoti/Dunedin for a long time now. By way of a warm-up, Eggleton read two of his own poems, "Distant Ophir", which recalled the Aotearoa of his childhood, and "Southern Embroidery" which catalogued a number of familiar southern scenes.

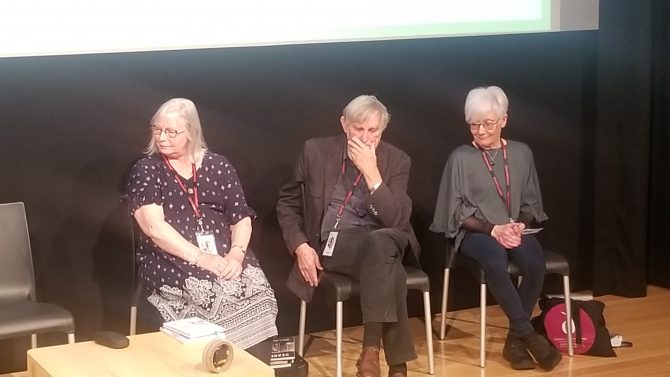

Cilla McQueen was the first of this august company to read. She spoke of how the landscape grounds her, both physically and psychologically. She read an early work entitled "Living Here" which talked about how Aotearoa was a string of small human centres surrounded by sheep, an animal that gave New Zealanders warmth and sustenance. McQueen read a beautiful villanelle called "Mining Lament" which had been inspired by an 1870 painting by Christopher Aubrey of an open-cast gold mine. She read some poems about Bluff which celebrated its weather and its seascape and concluded with another early poem, "How to Make a Wind Harp".

Next up was James Norcliffe whose first poem, "Back of Our Place" recalled his childhood adventures in Kaiata on the West Coast where he and his playmates avoided being incinerated by the burning sawdust heap at the nearby sawmill. Then he brought us closer to home with a poem about the delights of diverging from the road to Akaroa through Motukarara and out to Birdlings Flat where the lizards sunbathed on the stony beach and the Pacific pounded the steep gravel shoreline. His next poem, "Gershwin on the Car Radio" recalled his road trips from Dunedin to Christchurch, passing through such tiny hamlets as Hampden. His poem, "Mapmaker's Mistake" was predicated on the knowledge that mapmakers would insert a deliberate mistake into their maps to avoid others plagiarising them. Norcliffe concluded with a poem, "The Harbour", that celebrated the place where he has lived now for many years, Church Bay.

Kay McKenzie Cooke was born in Southland and her first poem was called exactly that. It was about a car journey heading south "strumming with speed". She said she had realised her titles tended to the prosaic, but I can assert that the poems were certainly not. There was "Near Alexandra" with its lovely image of the "accordion of sun" and "Bucklands Crossing" where the poet heard "the glottal stop of magpies" and the "cocksfoot-worrying crickets wind and wind their watches". In "Maniototo" she sees "tussocks as flexible as air" and her birthplace of Tuatapere gives rise to her poem, "Rivers, Hawks, Hills and Trees". Cooke concluded with an early poem, "Tongue-tied" which she said was about her relationship to the landscape of the lower South Island.

Although Owen Marshall is known as the pre-eminent short story writer of Aotearoa, he has also published four collections of poetry. Marshall has spent the bulk of his life in Oamaru and Timaru. He read "Danseys Pass" with its image of "standing solitary upon the lion's back" and "Night Rain" about walking home from a maimai and being grateful to feel the rain falling. "Winter Sun" pictured that giant star "sliding down the blue sheen sky" and "Dunstan Dog in Winter" continued the theme of coldness with the "stroppy unseen bugger" barking to be let off its chain. "Monarch" was a beautiful poem with the poet observing the "monarch chittering by" and spotting its "frayed wings" indicating its life was nearing its end. Marshall finished with a small slice of life poem, "Small Child on a Trampoline" where he observed a little girl bouncing "fearless and alone".

Bernadette Hall read from her latest book, Fancy Dancing: New and Selected Poems 2004-2020. She opened with a poem about a mountain that Pākehā colonists named Mount Grey to honour Governor Sir George Grey who was the Premier of New Zealand between 1845 and 1879. Hall said she preferred the Māori name which was Maukatere (floating mountain) and described how, when the mist formed around its base, the mountain's summit did appear to float above the earth. Local Māori believed that the spirits of their dead departed from its summit to journey to Cape Reinga/Te Rerenga Wairua from whence they returned to the land of their ancestors, Hawaiiki-A-Nui. Hall then read what she termed "bad girl sonnets", one a love sonnet in which she rose "slowly into the light of your face". She read a poem exhorting the nearby Pacific Ocean not to inundate her Hurunui home. Hall spoke of how she was born in Central Otago and her father died of a heart attack when she was only sixteen. She observed that time seems to be circular and how, as she herself aged, she thought more about her father. She addressed her dead father in a poem inspired by a photo of her mother holding a young Hall who was dressed in a flowery dress. Hall concluded with a poem entitled "From the Hymnal of the Short-Tongued Bees".

As this was the last poetry-themed WORD Christchurch event that I attended, I would have to conclude that, as far as WORD Christchurch Spring Festival 2020 went, to borrow from the rugby argot: "Poetry was the winner on the day".

All photos by Andrew M. Bell

Listen: Audio recording of this session

WORD Christchurch

- View our page on WORD Christchurch Spring Festival 2020 for reports, articles, and interviews

- Folllow WORD Christchurch on:

Add a comment to: Poet Laureate’s Choice: WORD Christchurch Spring Festival 2020