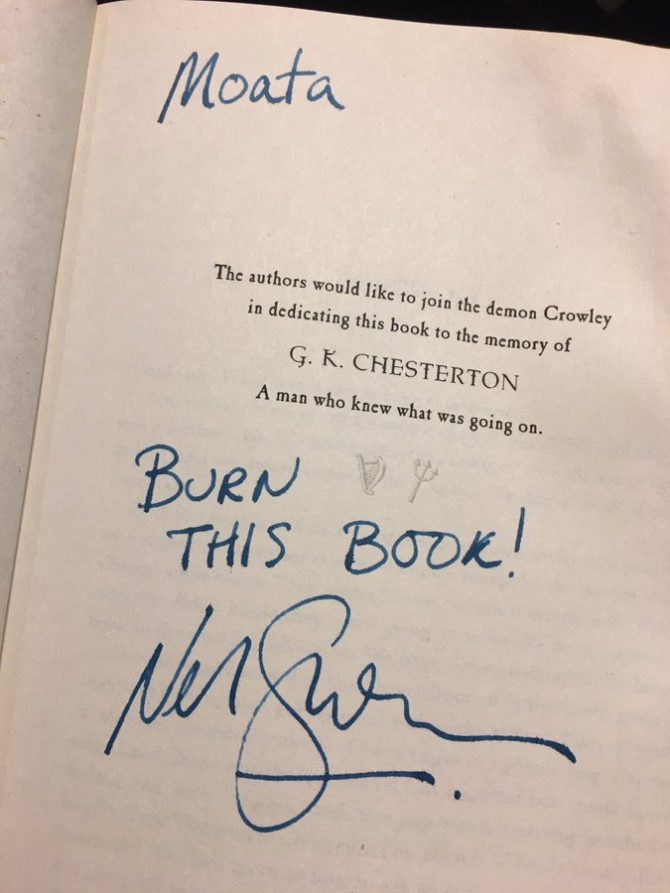

Neil Gaiman, fantasy author, is seated at the signing table in the foyer of the Aotea Centre. To his left are a selection of pens, next to those a plate of fruit - apple and pear slices, grapes, halved strawberries, even some cucumber - along with what looks like a Crown Lynn cup and saucer. The cup is currently empty, and the fruit is as yet untouched, but I can well understand why both have been supplied. We are currently cresting into the third hour of book signing with the end of the queue still not visible as it disappears out the door and into Aotea Square.

In the end all books will be signed, all fans chatted with but it takes 5 hours to get through them all.

By the time I've had my two books signed (one for me, one for my son), I've been queuing for a little over 2 hours and I'm so elated to be free from its confines that I do a little dance right there in the middle of the foyer. It's as much to get the blood going through my legs again as anything (I'm glad I wore my comfiest sneakers).

For his part, Neil (who encourages any readers who wanted to write about him to use his given name, as yes, "we're friends") seems perfectly comfortable, affable and relaxed, despite having spoken with literally hundreds of people before me. He has a little time and chat for everyone, and it is all very easy and nice. If this were one of his own stories this scene would be too nice for comfort - the fruit underneath on the plate would be in a state of decay, the contents of the cool green teacup tainted with something evil. But the only menace detectable... is between the covers of his books.

His session with chair Nic Low (WORD Christchurch co-director) was a delight with ideas and musings flowing freely. You get the sense about Neil* that all you need do is nudge him towards a topic of conversation and he'll have something thoughtful to say about it or some self-effacing, amusing anecdote to hand. He is a storyteller, after all.

He looks the part of the slightly offbeat author - jacket, t-shirt and jeans all in a black, a greying head of fluffy hair (a look that I believe Billy Connolly has been know to call "windswept and interesting"). As he settles into an armchair opposite Low he seems thoroughly comfortable - but this is hardly his first gig. He gives the impression that he could do 3 of these before breakfast and it would all be pretty effortless.

By way of introduction Low skirts past listing accolades (of which there are many - Hugo, Nebula and Locus awards abound - there's so many his Wikipedia page only lists a selection of them) and instead informs us that if you stacked all of Neil's published works up they'd make a stack 7 feet tall.

Quite apart from the quantity of work, there's also the fact that Gaiman has never limited himself to one format. Novels. Check. Short stories. Check. Graphic novels. Check. Radio play. Check. Screenwriting. Check. He's even played himself in an episode of The Simpsons. At this point it feels easier to remark on what he hasn't done (headlining a show in Las Vegas? A super spooky episode of Shortland Street?).

Auckland Writers Festival. Check.

Neil is currently a resident, with wife Amanda Palmer and son, on Waiheke Island, and prior to that he was living on the Scottish Isle of Skye (world famous for that song they used to make primary school children sing at assemblies). And so it's perhaps not too strange that, among the topics he's been thinking about lately, is islands and "island mentalities". Low probes him further on what he means by "island mentalities".

"Islands are places where for hundreds, perhaps thousands, of years people have learned you can't run away from things because you're still on the island."

He goes on to point out that you can't get away from people either since they too will still be on the island. Islands also have "their own kinds of phenomena" explaining that it's not unusual to find giantism or dwarf species on islands.

Another topic at the forefront of his mind is stones, and he talks about the kinds of stones you might find on the Isle of Skye, including one with a neolithic hole bored into that he uses to keep his bin lid closed in the wind, and how it's possible to discuss the difference between a drystone wall on Skye vs one in Yorkshire. And yes, some of this stone obsession might make it into his work at some point but there are the readers to consider:

"I know it will come up in fiction... at the point where I know I won't make it dull."

The discussion moves on to the topic of the pandemic and how that might be influencing Neil's work which he thinks it definitely is but it's not always immediately obvious what effects these events have. Sometimes you're writing about the pandemic without really knowing that's what you're writing about.

"...writers will be writing about the pandemic, whether they know that's what they're writing about or not, for generations to come..."

This question sends Neil off on what seems an unlikely tangent, at least to start with, as he discusses travelling to Jordan in 2014 where he spoke with Syrian refugees, wanting to know why it was they'd made these perilous journeys. After all, "it takes a lot to get anybody away from their homes" and he was struck by how these were nice middle class people, dentists, for instance. "They were us", he reflects. What could have motivated them to cross deserts?

In answer he heard about how the heavy tanks coming through town had crushed the water and sewerage pipes beneath the road, that the landmines in the fields cut them off from food supplies, that they ate all the food they had and the lifestock, and eventually all the cats and dogs. That the water they gathered wasn't clean enough and made them sick. His take away from this story of one family was that civilisation is much, much more fragile than he'd imagined.

"These are fragile systems...we think they're incredibly robust..."

A notion that Christchurch people will be all too familiar with.

So this story did circle back to the pandemic in that these ideas of the fragility of civilisation have been sitting in his head ever since 2014 and so for him, the pandemic has just reinforced this feeling that civilisation isn't the fixed, ever "embiggening" thing you might have assumed.

And of course New Zealand's version of the pandemic isn't quite the same as how it's played out in other parts of the world. And people's relationship with fiction and stories has sometimes changed because of this.

"I know people who have been in an apartment for a year. For all those people fiction gave them an escape. It gave them a place to go - a place that wasn't the four walls they lived in."

Anyone who's read much of Neil's work will know of his fondness for fable, fairytale, and myth. Titles like American Gods, Norse Mythology, The sleeper and the spindle, and many others are concerned with the mythic or the folkloric. So when Low asks "What kinds of myths and gods do we need in a crisis?" you might well expect Neil to be the perfect person to ask. But Neil's answer is a simple and unvarnished truth: What we need in a crisis is friends.

But also maybe some "illicit VPN methods" so that you can watch Wellington Paranormal from the UK.

"I just want to go and spend time with those nice police people."

And who wouldn't? I'd happily have Officer O'Leary round for an afternoon tea. Less so, Minogue. Or the monsters.

Eventually the discussion turns to Neil's latest book, The Neil Gaiman Reader (it's at this point Neil says his own last name and so I can say definitively that the first syllable is pronounced "gay" rather than "guy" - I had been bouncing around between the two for far too long).

As a volume it's what I would describe as a "chonky boi". You could inflict serious damage on someone with it (should you have a dark wish to). Neil claims it came about because he was getting sick of people asking him what work of his they should read - from now on he will be able to point them to this. Neil had people vote on the internet for their favourites and from this he selected the top 47 stories - topped up with a few novel extracts it has 52 readings in it (hence the size) and is presented in chronological order.

Proofreading it and reading through that body of work allowed for some retrospection on both his "obsessions" and his writing.

"Every now and again I would just go 'I really liked that phrase, didn't I?'... 'Hair so fine it was almost white'. You should really only use something like that once...

The only story in the collection that he included that didn't earn its spot from the online voting was the very last one, "I thought, I love you, little story and nobody's read you". So in it went.

There's a story called "Monkey and the Lady" I wrote for a 2017 @DaveMcKean anthology that people didn't vote for because, I suspect, very few people had read it. And I love it. So I made an authorial decision and put it in at the end. https://t.co/Ww5zLZeNyE

— Neil Gaiman (@neilhimself) October 8, 2020

Neil then takes to the podium and reads a story from the book. A spooky, big, old dusty house story called "Click clack the rattlebag". And we are all suitably spooked and rattled by it.

Low then guides the conversation towards Neil's relationship with Hollywood and the numerous adaptations of his work (many of which have never left development Hell, so much so that he once made the cover of a Hollywood trade publication as having had "more things optioned and not made than anybody else"). He shares a delightful story of awful time he and Terry Pratchett had trying to get an adaptation of Good Omens made.

Ahead of a meeting with some Hollywood execs Pratchett suggested they needed a "safe word" so that if either of them felt it was going south they could get out of the meeting and go to the airport. Wanting something unlikely for the "safe word" they settled on "Biggles", of the fighter pilot juvenile book series beloved of many an Englishman. Five minutes into the meeting Neil looked over and saw Pratchett with his hands stuck out at either side of himself, playing at being a Sopwith Camel. Pratchett's instincts were correct and it all went terribly, as it turns out.

beloved of many an Englishman. Five minutes into the meeting Neil looked over and saw Pratchett with his hands stuck out at either side of himself, playing at being a Sopwith Camel. Pratchett's instincts were correct and it all went terribly, as it turns out.

But other collaborations have been more successful as the recent TV adaptation of Good Omens shows. Neil says that the key to working in Hollywood is to find people you trust and to work with them and not anyone else.

When the time for audience questions comes around, several neat and orderly queues form behind several neat and orderly microphones on stands. It's here that we learn that it's okay to call him "Neil": "I like to think of my readers as friends I haven't met yet...", and that his wife's favourite piece of his work is The ocean at the end of the lane, "because it has emotions in it".

Another audience member asks if the statement that Pratchett made that Neil wasn't "a hat person" is still true (Pratchett was very much a hat person). Has he found his hat yet? The answer is sadly, no. Though Neil feels in his heart that's he's a hat person he claims to end up looking like Harpo Marx when he puts one on, with his hair sticking out. Pratchett, who died in 2015, even left Neil one of his hats which on Pratchett made him look "halfway between an author and a cowboy" but which had a rather different effect once perched on Neil's head:

"I look like a rabbinical assassin - a rather awkward Jewish hitman."

So that's a "no" to hats then.

A child in the audience asks if he ever dreamed he'd be a writer or as successful as he has been. Neil replies that he certainly daydreamed about it. At an age when other kids were daydreaming about being professional footballers his fantasy was to kidnap all his favourite writers and get them to write "... a giant novel to my specifications and publish it under my own name". He says, for some reason it didn't occur to him that he could do the writing part himself. But certainly his aspirations were to a level of success where he'd be able to have a family and feed himself and have a roof over his head. Imagine his surprise that after his first book came out a car or a house didn't magically appear, "Oh, do I have to keep writing?"

And he did. Seven feet worth, in fact. But he admits that he didn't expect the level of success that he now has just because of the genre nature of his work which he characterises as "working over here with the weird kids". It turns out "we're all weird kids now".

When asked what other career path he might have taken he admits that none of the ones that appeal actually exist - "I would have loved to be a freelance religion designer".

Where do you stand on guilt? How many days off do you need a year?

But this likely stems from his affinity for creating different ways of seeing the world, something that fiction and made up religions have in common.

Another questioner wants to know if there will be more Miracleman. To which Neil is as non-committal as he can be while also saying that something is in the works (though apparently not for the first time). His suggestion? Anyone interested should get "moderate hopes up".

One last question looks to dig into the intertextuality of Neil's work, that is, the relationship between it and other already existing works. How does Neil pick up on the influences on his work. Neil says that this is partly just about being honest. Some writers like to pretend that their work emerges fresh, as a whole that doesn't rely on any previous work. But Neil believes in Pratchett's way of thinking about it as stories coming out of a communal stewpot. If you're very lucky you get to chuck the occasional ingredient in of your own but for the most part we're all taking from a great melange of cultural references, and stories already told.

Part of the reason he identifies some of these influences in his book The view from the cheap seats is so that "it means young writers don't need to feel guilty".

Part of the reason he identifies some of these influences in his book The view from the cheap seats is so that "it means young writers don't need to feel guilty".

"You got it from somewhere, you did something to it, you passed it on... All art is a conversation..."

And what a relaxed and convivial conversation it's been.

I'd say this was the end, but then there's that signing queue feat of endurance to come...

*It still feels weird to use his first name even though he said we could.

Add a comment to: The Universe of story: Neil Gaiman at Auckland Writers Festival