Last year, as part of WORD Christchurch's Autumn Season, James Gleick spoke on his wide-ranging cultural history of Time Travel. If you have any interest in, as Doctor Who puts it, "wibbly-wobbly, timey-wimey stuff" it's a great read.

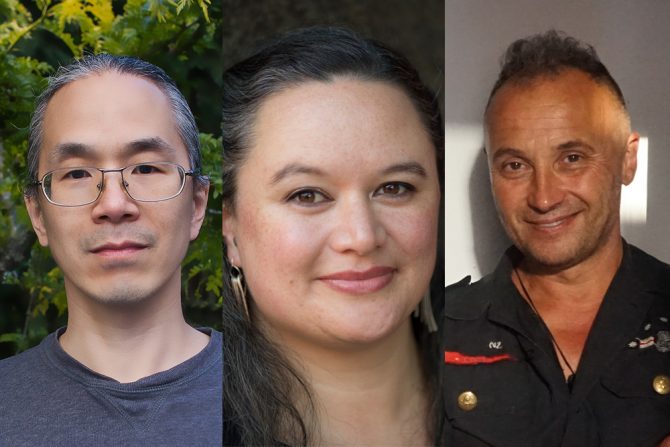

This WORD Christchurch Festival session brought together American author, Ted Chiang (whose novella, The Story of Your Life, became the acclaimed film, Arrival) and kiwis Whiti Hereaka (author of YA novel Legacy), and Michael Bennett (author, with Ant Sang of graphic novel, Helen and the Go-go ninjas). What, I wondered, would the writers of such temporally transformative works have to say on the topic?

As it was, I was feeling a little like I'd slipped forward in time myself - I woke up that morning to discover that it was September already. How had that happened?

In fact, the first question made reference to James Gleick's aforementioned book - Ted Chiang disagreeing with Gleick's assertion that The Time Machine by H. G. Wells represents the first example of a story featuring time travel, and that Wells is the originator of time travel in that sense. Rather, he feels that time travel tales are more a modern take on a prophecy story, a common tale since ancient times. The fact that story prophecies always came true was a reflection of the ancient world's belief in fate. Your destiny lay ahead of you, and no matter what you might do to try and change it it would always find you. If there was a shift, Chiang believes, it was one away from believing in fate towards believing in free will.

This is something you can see in a story like Charles Dickens's A Christmas Carol. Ebenezer Scrooge, having travelled to a possible future, escapes his fate by changing his ways. He exerts free will and the course of his life is altered. By comparison, The Time Machine's protagonist doesn't engage with the possibilities of time travel at all, moving through time but not making any attempts to alter its course (which, now that I think about it, is kind of the point of time travel stories, by and large).

Michael Bennett and Whiti Hereaka both made comments as to the importance of prophecy in Māori culture. And Bennett pointed out that Māui himself fought time, slowing the sun to extend the length of our days.

When asked about the pervasiveness of the genre, Bennett reflected that we all understand "the unfairness of time" and deployed a rather splendid extended metaphor of the time as a river - we have not choice but to flow with the current, which at certain times in our lives seems too slow, though as we continue along we try to slow it down, looking for the eddies that might delay our arrival at our ultimate destination.

Chiang's motivation for writing The story of your life was, through the character of Louise, exploring an aspect of human nature "the knowledge that in the future comes great joy and great sadness and coming to accept that both things lay ahead of her".

Hereaka's reason for writing a time travel story grew out of her desire to tell the stories of soldiers in the First World War's Māori Contingent - she hadn't previously been aware of this part of our history and wanted a way to share it, moreover she wanted to have those characters speak in their own voices, not via a modern one. Later on, in response to an audience question about creating voices from the past, she says that her theatre background helped but it also took some research, reading novels of the time, oral histories and where available listening to recordings.

She also had a really interesting perspective on the relationship between the writer and the reader saying:

I believe writing books is an act of manaakitanga - welcoming people into your world.

When asked about their favourite time travel stories Hereaka admitted that television was her go to - series like Life on Mars and Ashes to ashes as well as Doctor Who (Jon Pertwee was her Doctor but the imminent arrival of a female Doctor is something she's really excited about). Bennett, somewhat unsettlingly, admitted to reading Kurt Vonnegut's Slaughterhouse Five at the tender age of ten, and it has remained a favourite. Chiang favoured the movie Back to the future which he says is "a Swiss clock of plotting" for which he has "immense affection".

The craft of storytelling was highlighted by an audience question about the constraints that time travel places on the story. Bennett confirmed that not making it too hard for the reader to follow can be a concern. And Chiang pointed out that Time Travel as a device is "the universal acid that will dissolve any container you put it in" in terms of story. Suddenly your protagonist's problems can be fixed by going back in time and doing it again. For that reason Time Travel stories usually have some "rules" or constraints applied to them to stop the easy fix from occurring. And no, these constraints may not hold up to close inspection - but you're only looking to suspend disbelief for a time, to tell a story.

Hereaka was in agreement with Chiang on this saying:

That's what stories are... It's about solving problems and humans finding out what it is to be human.

When asked if they could time travel what they think they would do, Hereaka said that period dramas sometimes make her wish she could live in another era but she'd come to a realisation - "no, you wish you were rich". So wherever she goes in time she wants to be well funded.

Chiang doesn't think that "there's any period in history that I would be better off in than right now" and that trying to change history at all is not a good idea as you can't have any confidence that the changes you make would work out.

For fans of sci-fi and time travel fiction this session gave some interesting insights into what these kinds of stories can tell us about ourselves, and the challenges they pose to the storyteller. A session that I'm happy enough to have spent some forward travelling time in.

Find out more

- Our WORD Christchurch 2018 page

- WORD Christchurch festival programme

Add a comment to: Timey-wimey stuff: WORD Christchurch Festival 2018