OMG. The Faraway Near changed the TSB Space at Tūranga completely!

I didn't recognise the place, turned into a bar with the most wonderful kitsch. Could Tommy Orange see me from his screen, typing away at the media table? It was awesome to see him. I couldn't quite believe it.

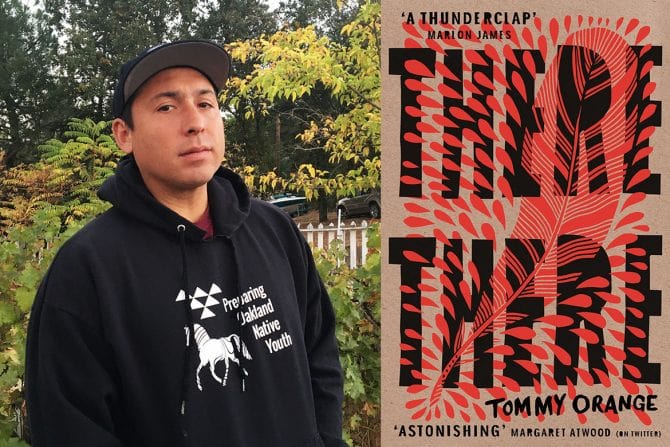

The thoughtful, insightful Tommy Orange (Cheyenne, Arapaho), spoke with the also pretty amazing Jess McLean (Ngāti Kahu, Ngāti Hine, Clan O’Hara and Clan Maclean) about belonging, not belonging, his hugely successful book, There There and the similarities between Thanksgiving and Waitangi day, from an decolonisation point of view.

Jess, a lecturer at Aotahi, School of Māori and Indigenous Studies at the University of Canterbury, started proceedings with a pepeha; introducing herself, and welcoming Tommy Orange. This gathered the excited audience's attention, and gave the event an air of intimacy for what was a robust and genuine discussion: personal, profound and poignant.

Orange has achieved great success with There There; his first book. His second book is on its way. I'm pretty excited about that. I loved There There. It's a point of view the world needs to read.

Orange is a graduate of the MFA program at the Institute of American Indian Arts,

Tommy, born in Oakland, California, reads from the interlude (front?) to There, There - a passage that examines what does being native means, and what being from Oakland means to him:

"Urban Indians feel at home walking in the shadow of a downtown building. We came to know the downtown Oakland skyline better than we did any sacred mountain range, the redwoods in the Oakland hills better than any other deep wild forest. We know the sound of the freeway better than we do rivers, the howl of distant trains better than wolf howls, we know the smell of gas and freshly wet concrete and burned rubber better than we do the smell of cedar or sage or even fry bread – which isn't traditional, like reservations aren't traditional, but nothing is original, everything comes from something that came before, which was once nothing. We ride buses, trains, and cars across, over, and under concrete plains. Being Indian has never been about returning to the land. The land is everywhere and nowhere."

Orange talks about character Dene Oxendene's interviews, which are a central part of the story. Dene is a projection of Orange's own experience undertaking the same project. The interviews at the powwow ask what 'being native' means to each person. Common themes emerge - not having a dad, or having an absent dad, having native pride but, due to mixed parentage, it doesn't feel true.

"I can't claim being native if I don't know anything about it" says Orange,

making us laugh with his comment,

''I just don't know about this blood shit."

Jess: "What is authentic indigenous identity? Is that what There There is about?"

Orange talks about a disconnect with native culture and the importance of language; saying how much he appreciated Jess's introduction in Te Reo. He points out that when people have no sense of belonging, there's a strong inclination to gain a sense of identity from joining a gang. And a feeling of not wanting to obey the law when you're disenfranchised.

Tommy's mom is white, while his dad is Cheyenne. Sometimes, says Orange, the sense of being from Oakland is stronger than his sense of belonging in Oklahoma, where his father is from.

How do you describe the tension between reservation life and urban life?

There are many similarities here between the Māori and Native American experience. Jess shares that there was twenty percent urban movement to the city in the fifty years between 1930 and 1980. In the U.S. there was a staggering seventy percent movement from reservation to city between 1960-2010.

Urban centres and Indian communities were strengthened, says Orange, by retaining their ties to tradition and language. Tommy himself regularly visited family in their reservation in Oklahoma, and they visited him in Oakland. Like Māori, there is a strong value in whānau.

"Getting us to cities was supposed to be the final, necessary step in our assimilation, absorption, erasure, the completion of a five-hundred-year-old genocidal campaign. But the city made us new, and we made it ours. We did not move to the cities to die."

Jess says she found the above passage really powerful: Orange's text suggests agency in urban migration.

Māori are often not seen as not having control over urban migration; it's seen as 'something done to us' says MacLean; implying that Māori were passive, operating from a place of survival.

But when you make new life, its more than just survival. Orange emphasises it's not 'Poor us.' There are a lot of stories of the forced assimilation of children, he says, 'but they couldn't assimilate us.'

The brilliance of tradition is in adaptation – there are two tribes of Cheyenne peoples:

"...you can't just be one thing to be authentic. Colonisers think they're higher up on the chain and that's completely wrong."

In Jess's experience to be authentic often means, 'how brown are you?' or, 'how well can you speak the language? Jess, a lecturer at Aotahi, School of Māori and Indigenous Studies at the University of Canterbury, says she is very wary of universalising indigenous experience.

Should texts be de-colonised? Orange says his next book actually focuses on language.

"There used to be a saying; 'Kill an Indian, save a man.' "

Orange's father's language, Shattaya, is considered a dead language. A change in thinking would be to change the view that oral histories are a lesser thing; a theme of There There. Text is a phonetic representation; 'but it's still a sound that fires phonetic sounds in my brain!'

Tommy says he is wielding English as a weapon: 'I believe in what writing can do.'

What is the response to There There from your own community?

Orange says that in the Cheyenne and Arapaho communities, there is a lot of corruption, misappropriation of funds and casino money. He honestly says, 'I don't know how to deal with that.'

From the community of Oakland there's been an exuberant response: 'Yes! we see ourselves in what you're writing.' And 'Oh man this is refreshing, giving me life!'

While white people say, 'Why did you write something so heavy?' (Cringe)

Jess points out these are dangerous waters to navigate: tropes in characters such as addiction and alcoholism. Tommy writes from his own experience – 'because it is personal to me' – the writing bringing out personal demons: 'my dad is an alcoholic and a medicine man.'

Do you feel lumped with representing your people, or do you think there's room for indigenous writers as an individual?

"I knew I would have a platform, but you don't know anything would...happen to it! This could reach a lot of people..."

Jess quips: It sounds like you were allowed to explore your own writing and experience without being a famous award-winning writer!

Personality and specificity, says Orange, is the key to universality "The more you dig into your own thing, the more people will feel you."

Tommy's new book is being sold as a sequel. But it's a bit of a prequel as well. While on tour in Sweden Orange heard of a 'prison castle' in Florida. It took him down a rabbit hole. Seventy five Southern Cheyenne were taken there from Oklahoma 1775. He speaks of cultural genocide; Indian children made to cut their hair to look like white children, with before and after pictures with them in military uniform. The new book also focuses on before and after, with a pandemic element: the Spanish Flu.

How do you keep yourself safe spiritually, culturally; emotionally?

Tommy says the process of writing itself helps, and running. 'And I'm also a mess! I don't always handle...'

There is both pain and possibility in There There. Where does Tommy see his tribe now?

His dad is one of five native speakers left. His potential is not being used by the tribe - there is internalised oppression and financial corruption. His people were badly hit by Covid....lots of meth.

'We carry a lot of pain - a lot of indigenous people do. And within that pain is the possibility for transformation.'

Who are your inspirations for your creative practice?

James Welch, author of Winter in the Blood, fell in love with his wife at a book club when they were the only ones to turn up. This book was the beginning of Orange's understanding of the way you can use language to change experiences. Tommy is inspired by reading authors from all over the world, particularly South America. He has taken an unconventional path as a reader; with no one telling him who to read, 'I read whatever voice spoke to me.'

'A lot of Native American literature didn't speak to me, as I was from the city. I had to move away from that and come back to it.'

Your views on Thanksgiving?

'In the prologue (of There There) I tear it down – but how often do we all get time off at the same time?'

There are similarities here to Waitangi Day. Yet Thanksgiving is a celebration behind the massacre of Indian people, murdered while offering food and hospitality to American settlers.

Tommy Orange stopped celebrating Thanksgiving four years ago. He says it's been a struggle. He's up against sneak (food) attacks from his mother-in-law, and on the Native side, the family gather together anyway, so it's 'lets make fry bread, and we won't call it that (Thanksgiving)'

" ...Anyway I tell this story because our story is still told with the arc of America and stuffed turkey. It's sickening – but we all do it; I like turkey too. But we have to say what it's about!"

Jess says that Waitangi Day and Bob Marley's birthday, particularly his references to the Israelites, have played a significant role in Māori culture, when there were once no examples of 'brown greatness'. Tommy says that some Native Americans believe that Bob Marley could be the reincarnation of Sitting Bull...

Find out more

So if you're not into celebrating Thanksgiving, why not try this?

- Speakers for National Native American Heritage Month - Penguin Random House Speakers Bureau (prhspeakers.com)

- Let's learn some Cheyenne

- fionaccl reviews There, There

These Native American authors are really successful right now:

For more Native American information and characters:

Add a comment to: Belonging and not belonging: Tommy Orange at The Faraway Near, WORD Christchurch