It's a slightly different panel line-up than the one that was advertised at this Owning History discussion on a sunny Sunday at The Piano.

Ngāi Tahu leader, Tahu Pōtiki's passing earlier in the week means that his cousin, academic Sacha McMeeking is now unavailable, presumably attending the tangi in Otago. Her place is taken by colleague Jessica MacLean (Ngāti Kuri, Ngāti Hine, Clan O'Hara, Clan MacLean), a lecturer and "emerging academic" at Aotahi School of Māori and Indigenous Studies at the University of Canterbury.

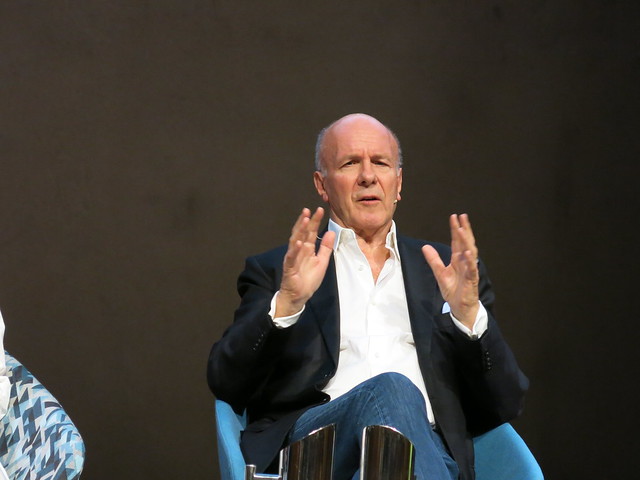

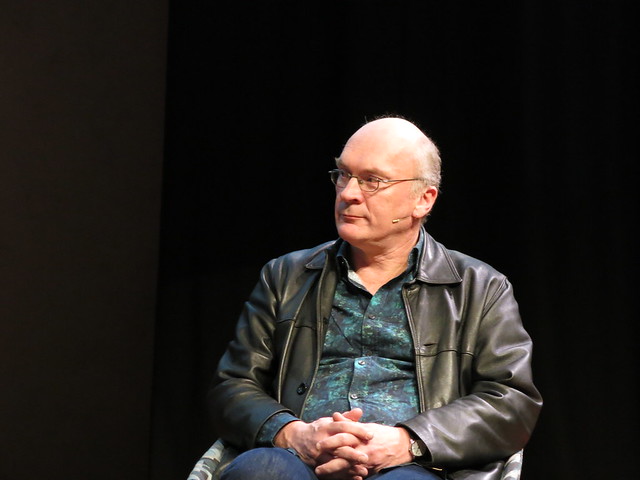

The other two panellists, Simon Winchester and Vincent O'Malley barely need an introduction but panel chair, University of Canterbury's Peter Field gives the audience plenty of background on both, running through O'Malley's academic credentials - the first person to get a PhD in New Zealand studies, his 20 years experience as an historian - and giving a potted history of Winchester's life that reads like some kind of Boy's Own Adventure, but for grown ups. This includes being expelled from school for "illlicit science experiments", his time in Washington D. C. during Watergate, his roles as writer, journalist and broadcaster, and his O. B. E. (which Winchester by way of interjection says stands for "Other Buggers' Efforts").

Field opens the discussion with the question of whether history actually can be owned. And what does that mean?

O'Malley says that owning history is really just about being honest with ourselves... especially about the bits we'd rather forget. It's about being mature enough as a nation to accept that history - throwing some homegrown poetry into the mix, in the form of Allen Curnow's 'The Skeleton of the Great Moa':

"Not I, some child, born in a marvellous year / Will learn the trick of standing upright here."

More than that, says O'Malley, acknowledging that history is the basis of genuine reconciliation. We can't have a dialogue without understanding that history. He explains this idea with a local example, of returning to Christchurch in 2011 (O'Malley formerly studied at Canterbury University) and being unable to understand where he was due to the lack of familiar landmarks in the postquake city - without the context of the surrounding buildings he couldn't make sense of the streets. When then Prime Minister, John Key said New Zealand was "settled peacefully" he wasn't being honest.

Winchester, who now lives in the United States had examples of this from his adopted home, certainly slavery, for one, but also the internment of 120,000 American citizens of Japanese descent in camps during WWII is another. And Americans are not taught about it in school, leading to widespread ignorance on the topic.

The topic of education of the general populace of its history is one that will come up multiple times during the discussion.

MacLean brings it back to New Zealand history, expanding on O'Malley's earlier point: There's a reason a Crown apology is the first part of the Treaty process. And what's true for a nation is also true at a personal level, "we know it in our own interpersonal lives that when we muck up, owning what we've done is the first step".

Field, surely looking to elicit some emphatic denial, then suggested that the panel might be emphasising the negative, since New Zealand's history is quite positive in contrast to that other countries, like his own country's legacy of slavery.

O'Malley took the bait explaining that "deconstructing the myths of a nation is what historians do", and that that narrative - the "aren't they lucky they were colonised by us" one - was not one that Māori shared. The idea that after a bit of conflict (The Land Wars) that everyone settled down and lived happily every after was simply not true for Māori who had to live with the consequences. In 1850 Māori were leading the economy. By the 1860s, almost overnight, this was gone. The tendency to pat ourselves on the back by saying "look at Australia - it's so much worse there" is just an excuse to avoid owning up to our own history.

So where are we as a nation on the path to owning our own history?

MacLean points out that at her high school the only history option was Tudor history. She only learned about Parihaka at university. "There's a lot of good will... but we're not there yet".

Winchester, who seems a man overwhelmed with an abundance of curiosity (a good trait to have in his line of work, I suppose), innocently asks if we've ever considered changing the name of our country, suggesting somewhat misguidedly that Australia has a more "neutral name", as it means "land of the Austral region" (in Latin). Muttering amongst the audience suggests that many are in agreement with MacLean when she points out that Aboriginal Australians might not agree on the name's neutrality.

The topic of the book that Winchester is working on, about the ownership of land, comes up. He's been travelling the world asking questions about different aspects of land ownership in places like the U. S., Holland, Latvia, Ukraine, and Scotland as well as Australia and New Zealand. What might we tell him about land in New Zealand?

For his troubles Winchester (and the audience) gets a very abbreviated history of land alienation by the Crown from O'Malley, who has been working in Treaty claims for 26 years - this is literally his life's work.

Before 1840, 66 million acres of land was in Māori ownership. Locally, Kemp's purchase - equivalent to 1/3 of the country, 20 million acres - was acquired for what would be £4000 in today's money. The Native reserves that were part of the agreement of that purchase were only a few thousand acres.

In the 1850s there started to be resistance to this wholesale loss of Māori land and the wars followed. The consequence of which was that the Crown were then "justified" in confiscating even more land. And The Māori Land Court which O'Malley describes as "an engine of destruction" moved even more land from Māori to Crown ownership as land that had previously been held collectively was passed into individual title, and once this happened it was so much easier for it to be sold, destroying whole communities.

The 1975 Land March was a turning point, the Waitangi Tribunal was established and 10 years later it was empowered to investigate historical claims which opened the floodgates. Most of the Waitangi Claims material isn't published and so most New Zealanders don't know that history.

Winchester's reaction to the news that most of this is not taught in our schools was incredulity, "this is outrageous". Well, quite.

MacLean adds that the Minister for Education, Chris Hipkins, has refused to implement curriculum change because schools can teach this history if they want to. But MacLean points out that under the current system it's still not happening so that's not really good enough.

Back on the topic of ownership, MacLean points out that the notion of ownership is culturally bound and partly a misunderstanding of what constitutes ownership has lead to some of our historical issues. She says that often when land was sold by Māori the sale was one of a usufruct nature, where it was the right to use the land that was being sold rather than outright ownership. Winchester seems delighted that someone has used the word "usufruct", while admitting that it is "a really ugly word".

Field wonders if some of our reluctance to learn New Zealand history is due to cultural cringe and the idea that "somewhere else is more important" (like Tudor England, perhaps?)

MacLean responds with one of the most unexpected yet deeply resonant (with me, anyway) analogies I've heard in a while, comparing New Zealand history with her first ever CD purchase, which was by New Zealand band, Supergroove. At that time (the 1990s) there was a huge amount of cultural cringe around Kiwi music - this has taken decades to move on from.

O'Malley points out that we have an incredible, rich history people with characters like Wiremu Tamihana (aka the Kingmaker), who was one of the most remarkable statesmen in New Zealand, ever. New Zealand history is not boring. But then he's made a career of researching it so either he's terribly biased or terribly knowledgeable... or both.

Winchester's own experience with our cultural cringe comes in the form of an interview with The Listener (said interview is in the last issue), wherein the interviewer asked if there would be a chapter about New Zealand in his new book... in an almost pleading way. I think we've all read enough articles and interviews with visiting celebrities to know that this absolutely happened. The only question is whether Winchester was asked if our scenery was beautiful enough and if he'd found the people warm and friendly. I do wonder sometimes if we should just have an official greeter at international arrivals wearing a "DO YOU LIKE US, FOREIGN PERSON?" t-shirt and be done with it.

Field nudges the discussion in another direction next, suggesting that New Zealand is a marriage of two very different cultures but that maybe those differences are what makes it work?

MacLean speaks a bit about being of mixed heritage, with deep roots on both sides, which is an increasingly common thing and, according to Statistics New Zealand, will continue to be so prompting this from MacLean "Is it arrogant of me to say maybe I'm the future?"

If it is, the audience isn't holding it against her so much as cheering her on.

MacLean also points out that common thread running through her Scots/Irish/Māori whakapapa is "an antipathy towards the English".

Winchester, who seemingly can't help interviewing people, even when he's on a panel with them, is curious as to whether the Irish/British lineage of O'Malley or MacLean translates into a concern with regards to Brexit. O'Malley acknowledges the potential for catastrophe while MacLean taps into the zeitgeist saying she views Brexit with "a mixture of amusement and despair".

The topic of te reo Māori comes up and MacLean, who is not fluent but learning, again uses personal examples to illustrate history. Her grandmother moved to the city in the 1930s - like many she thought the best way for Māori to get ahead was to assimilate. Speaking te reo in schools was still physically punished and so MacLean's mother was of a generation that lost the language. There were no kōhanga reo or kura kaupapa in those days. There has been massive backlash against the idea of te reo Māori being compulsory in schools, so yes, revitalisation is great, but we're not there yet.

The Q & A portion of the hour was a real mixed bag. Someone asked about the relationship between history and political science which prompted MacLean to point out that though co-ownership of the history is important she's wary of "an educative burden falling on Māori alone."

Another questioner, whose agenda may have been showing, asked to what extent Māori were owning their pre-European history? This seemed to be in response to the focus on the negative aspects of Pākehā-Māori history. Again MacLean was clear that there was a lot of focus on pre-European history but that statements on such are "very tribally bound". Not to mention that the ways that Māori have of looking at the past aren't necessarily that accessible to non-Māori, and include oral traditions, creative traditions and allegory. Moreover discussions about Māori history happen on marae and in Māori communities. Just because we don't see it in the public arena doesn't mean it's not happening.

Another question from the audience was a challenge and a provocation, with a man of Waitaha descent wanting to know when Ngāi Tahu were going to own up to their history. Waitaha were the earlier inhabitants of Te Waipounamu, the South Island and along with Hāwea and Rapuwai and were largely subsumed within Ngāi Tahu, which has its origins on the East Coast of the North Island. He and I both were disappointed that Sacha McMeeking wasn't there to answer his question - I would have loved to hear what she'd say on that. And this question really exposed the layered nature of history and its associated narratives.

Field posed a last question too - what has been the greatest pushback each panellist has received?

For O'Malley it's been from Hobson's Pledge but he looks on that as a badge of honour - if he didn't get pushback from them he'd be worried.

For Winchester it would be the time that he was bundled into a car in Ireland in 1977 and put "on trial" due to the "anti-Protestant" sentiments in some of his reporting. He was "found guilty", had a gun held to his head, and the trigger was pulled - it wasn't loaded.

MacLean, knowing that she couldn't possibly follow a story like that simply said "I can't beat that. Just gonna sit this one out".

Prior to taking questions from the audience, O'Malley had the opportunity to share his 3 point plan for improving knowledge of New Zealand history amongst New Zealanders and they seem fitting points to end on:

- Protect sites that connect us to history. Many scenes of historic battles in this country have a road running through them named after the general who commanded the British forces in said battle.

- "Teach the bloody history". It's as simple as that. Children are crying out to learn this history, it's the adults that are holding them back.

- Make more resources about New Zealand history for kids and adults, websites, books - more are needed.

These seem achieveable. Owning the history means that it'll be ours to share. So let's do that.

Find out more

- Read Moata's blog post preview of Owning History.

- Read Kate's blog post about Simon Winchester.

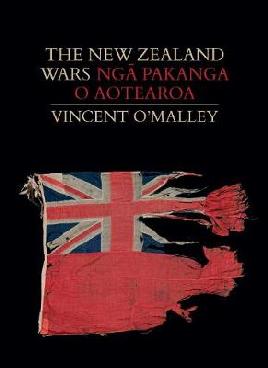

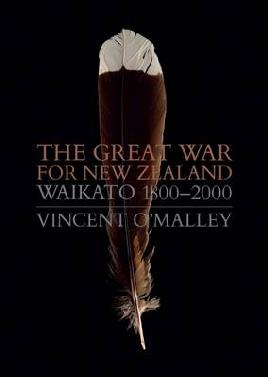

- Read Kate's blog post about Vincent O'Malley.

Find books in our collection by:

WORD Christchurch Shifting Points of View

WORD Christchurch presents Shifting Points of View — a spectacular line-up of New Zealand and international speakers to warm you up and get you thinking. Shifting Points of View runs from Sunday 18 August to Saturday 14 September 2019. Visit our page on WORD Christchurch Shifting Points of View for more information, previews, reviews, and WORD reading.

Add a comment to: Owning History: First own the history, then teach it