The Māori word for food is kai. Traditional kai involved food-gathering with extensive cultivation of the kumara (a sweet potato). Tī Kōuka (cabbage trees) were also harvested for the kauru and the taproot, both of which were eaten. Eels (tuna) were a favourite food of the Māori along with the many fish species found around our coastline. Another prized food was titi, or muttonbird, which was preserved in a process known as pōhā tītī.

Kai was an important part of festivals such as Matariki when people would gather to share entertainment, hospitality and knowledge at feasts. The Moon (marama) is central to the of harvesting kai on the land and at sea. A maramataka or lunar calendar was used to work out which days were the best to plant, hunt, fish and/or harvest.

Specific areas rich in food resources for hunting or gathering are known as mahinga kai or mahika kai. Different areas around Te Waipounamu were sources of different foods.

Explore our online resources

Search our catalogue

Pōhā Tītī

Library assistant Mary Brown explains the process that Māori used to preserve titi, or muttonbirds:

Tītī — is the Māori name for the muttonbird or sooty shearwater.

Pōhā — is the vessel used to preserve the muttonbirds.

The harvest of Tītī from islands surrounding Rakiura (Stewart Island) is of great economic, social and cultural importance to Ngāi Tahu. Some families still continue to use the age-old traditional method of preserving Tītī using the pōhā.

The interior partitions of broad sheets of bull kelp are separated by hand and then inflated to make large containers in which the Tītī were placed.

When the hot fat retained from cooking the birds is poured in and allowed to set, the flesh of the birds inside the pōhā is preserved for a very long time. The pōhā are protected with a covering of bark from the tōtara tree. A small woven kete is used to support the bottom of the pōhā.

Eighty-five-year-old Tiny Metzger has been making pōhā for as long as he can remember. The bull kelp and totara bark food storage container is an innovation at least 100 years ahead of its time. For Tiny and his whānau it is an annual tradition as they prepare to head to the Tītī Islands for the birding season. In this video producted by Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu he and his whānau gather the raw materials for and construct the pōhā used to contain the muttonbirds.

Kaimoana

Kaimoana (food from the sea) was important in the traditional diet and remains so today. Many species of fish were caught on lines or in nets, and shellfish such as mussels, pāua, pūpū, pipi, tuaki and toheroa were gathered from the shore.

Cyril Gilroy of Ōreti Beach digs for the much prized toheroa. In this video produced by Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu marae cooks tell tales of gathering this once plentiful shellfish.

Kai moana rather than meat was the main source of animal protein, fats, vitamins and minerals. Seafood was also used in social occasions as it demonstrated hospitality (manaakitanga) and generosity at hui or tangi. There is a highly organised set of customs (tikanga) to manage the way seafood is gathered and handled.

Other seafood includes eel and whitebait taken from inland or estuarine waters. Another source of protein was birds snared in the native forests.

Whitebaiting

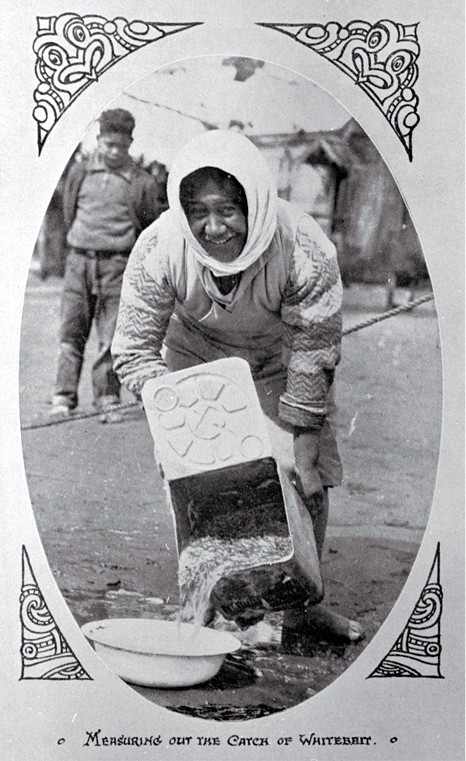

In Spring Māori caught whitebait at Te Waihora (Lake Ellesmere) using nets made from stripped flax, driving the fish into gravel groynes or catching them in nets. The catch might be placed in flax baskets lined with ferns and cooked in the hangi or preserved by drying either over a fire or on mats in the sun.

Whitebait (inaka or inanga) fishing was a well-established tradition before European settlement at places such as Puari. Mill Island, near the corner of Hereford Street and Oxford Terrace, was another well-known local spot. To this day eager anglers wade in the water during spring to net the delicacy, which are the young members of the galaxiid family.

Putting down a hāngī

In terms of cookery, Māori still follow the traditional Polynesian practice of cooking for large numbers in a hāngī. This earth oven or pit uses hot stones to create steam in which to cook wrapped food.

In terms of cookery, Māori still follow the traditional Polynesian practice of cooking for large numbers in a hāngī. This earth oven or pit uses hot stones to create steam in which to cook wrapped food.

The hāngī is the most widely used method of traditional cooking for Māori. “Laying” or “putting” down a hangi involves digging a pit in the ground, heating stones in the pit with a large fire until they are white-hot, placing baskets of food on top of the stones, and covering everything with earth for several hours before uncovering (or lifting) the hāngī. A hāngī is cooked in the ground on hot stones and steam should not to be confused with a Polynesian umu which is cooked on the ground on top of hot stones.

Volcanic stones are the preferred stone as it does not explode when heated.

Here is a quick synopsis from 'Genuine Māori Cuisine':

- Foods are prepared into three sections (and then everything goes in together):

- meats,

- vegetables,

- fish or puddings.

- Stones are heated until they are white-hot.

- Food is placed on top (watered down slightly).

- Food is covered with leaves then buried under dirt.

- The food is then steamed under the ground, with pressure from the leaves and soil.

- The hāngī must simmer for at least two to three hours and then the food is removed and served.

Links

- Ngāi Tahu Mahinga Kai A lifestyle series featuring 12 ten-minute episodes that captures the stories and essence of traditional food gathering practices passed down through the generations.

- Māori foods - Kai Māori Learn about traditional food gathering, preserving and cooking at Te Ara - The Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

- Marae Food Safety Food safety on the marae, food safety when hunting and gathering, and how to safely prepare a hāngi.