A brief introduction to the early European settlement of Christchurch which covers significant events, people and buildings. Links to recommended information resources and photographs from our collections are included throughout.

- First inhabitants

- Early European contact

- The first European settlements

- The Canterbury settlement

- New arrivals

- Settling in

- Canterbury 'Firsts' in 1851

- Towards independence

- Canterbury - a province

- Transport problems and the Lyttelton tunnel

- The boom years

- Christchurch becomes a municipal district

- New buildings

- Health and the city

- End of a provincial era

- 1876 - 1900 : important events and developments

- Sources

First inhabitants

The first people to live in the place now known as Christchurch were moa hunters, who probably arrived there as early as AD 1000. The hunters cleared large areas of mataī and tōtara forest by fire and by about 1450 the moa had been killed off.

North Island Māori (Ngati Māmoe and later Ngāi Tahu) arrived in Canterbury between 1500 and 1700. The remaining moa hunters were killed or taken into the tribes.

By 1800 the Ngāi Tūāhuriri sub-tribe of Ngāi Tahu were in control of the coast from the Hurunui River in the north to Lake Ellesmere in the south. Their largest settlement was a fortified pā at Kaiapoi. This was also a major trading centre for pounamu or greenstone.

The main track between Kaiapoi and another settlement at Rāpaki followed a path between the swamps and the two rivers, Ōtākaro (Avon) and Ōpāwaho (Heathcote). One of the two remaining patches of forest or bush was at Pūtaringamotu (later Riccarton), and was an important place for food gathering (birds, eels, fish and freshwater crayfish).

Early European contact

On 16 February 1770 Captain James Cook in his ship the Endeavour first sighted the Canterbury peninsula. He thought it was an island, and named it Banks Island after the ship’s botanist, Joseph Banks.

It was probably not until 1815 when sailors from the sealing ship Governor Bligh landed that Europeans first set foot on Banks Peninsula. In 1827 Captain William Wiseman, a flax trader, named the harbour (now known as Lyttelton Harbour) Port Cooper, after one of the owners of the Sydney trading firm, Cooper & Levy.

During the 1820s and 1830s the local Māori population fell. The reasons included fighting between different groups of Ngāi Tahu, raids by the Ngāti Toa chief Te Rauparaha from 1830 to 1832, and the impact of European diseases, especially measles and influenza, from which hundreds of Māori died.

More whaling and sealing ships visited the peninsula and harbour, and in 1837 Captain George Hempelman set up a whaling station on-shore at Peraki on Banks Peninsula.

In May 1840 Major Thomas Bunbury arrived on the HMS Herald to collect the signatures of the Ngāi Tahu chiefs for the Treaty of Waitangi. The Treaty had been signed by many North Island chiefs in the Bay of Islands earlier in the year on 6 February. During Bunbury’s visit only two of the Ngāi Tahu chiefs signed it.

The first European settlements

Captain William Rhodes first visited in 1836. He came back in 1839 and landed a herd of 50 cattle near Akaroa.

The first attempt at settling on the plains was made by James Herriot of Sydney. He arrived with two small groups of farmers in April 1840. Their first crop was successful, but a plague of rats made them decide to leave.

In August 1840 Captain Owen Stanley of the Britomart raised the British flag at Akaroa, just before the arrival of sixty-three French colonists on the Comte de Paris.

![The first house on the Canterbury Plains, Riccarton [ca. 1890]](https://christchurchcitylibraries.com/Heritage/Photos/Disc4/IMG0081.jpg)

On 7 January 1844 the first European child (Jeannie Manson) was born at Riccarton. A year later the Mansons and the Gebbies left Riccarton to establish their own farms at the head of the harbour.

The Canterbury settlement

In November 1847 John Robert Godley and Edward Gibbon Wakefield met to plan the Canterbury settlement.

Wakefield believed that colonisation of countries like New Zealand could be organised in such a way that towns could be planned before settlers arrived. These towns would be like a community back in England, with landowners, small farmers and workers, and with churches, shops and schools.

Early in 1848 the Canterbury Association was formed, and it was decided to name the capital city Christchurch after the college John Godley had gone to at Oxford University.

Part of the plan included the opportunity for the new settlers to buy land. This would supply the money needed for public works such as roads and schools. But first the land had to be bought from the Māori owners.

Kemp’s Deed

Governor Grey sent the land commissioner Henry Kemp to the South Island in 1848 to buy land for the new settlement. Sixteen Ngāi Tahu chiefs signed ‘Kemp’s Deed’, selling the larger part of their land for £2,000, but keeping some land for settlements and reserves, and those places where they gathered food (mahinga kai). This was signed at Akaroa on 12 June 1848. Ngāi Tahu were to be given back larger reserves of land once the surveying had been done. There was a mix-up over the reserves, partly because the map attached to the deed (the paper which had all the details of the sale) had different information. When Walter Mantell mapped the land in 1848 he deliberately cut down the promised reserves, allowing less than four acres per head instead of the promised ten. He also kept back from Ngāi Tahu some of their cultivated land and food-gathering places (mahinga kai).

New arrivals

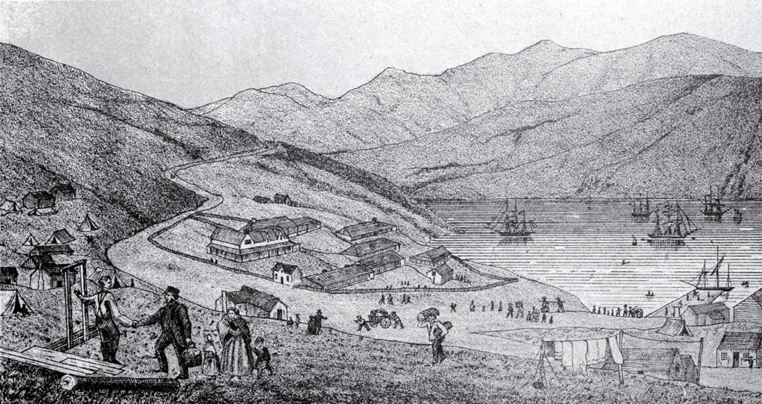

In December Captain Joseph Thomas, a surveyor, was sent to Canterbury to choose a site for the Canterbury settlement, and prepare for the first settlers. By the time that John Robert Godley, leader of the Canterbury settlement arrived with his family on the Lady Nugent on 12 April 1850, Captain Thomas had built a jetty, customs house and barracks accommodation for the newly arrived settlers.

![Cathedral Square, showing the Post Office and Godley statue, with delivery carts and pedestrians [ca. 1882] Burton Bros.](https://christchurchcitylibraries.com/Heritage/Photos/Disc1/IMG0054.jpg)

Godley and Thomas did not get on very well together, and Godley left for Wellington. He arrived back in Christchurch just before the arrival of the first four ship loads of settlers which had left England in September 1850.

The first of the ships, the Charlotte Jane, arrived in Lyttelton on the morning of December 16, 1850, and was met by Godley and Sir George and Lady Grey. The first ashore of the travellers, known as the Pilgrims, was James Edward Fitzgerald, who leapfrogged over Dr Alfred Barker, sitting in the prow of the rowing boat.

The second of the ships, the Randolph, arrived on the afternoon of 16 December, followed by the Sir George Seymour on 17 December, and the Cressy, on 27 December.

Settling in

The Deans brothers at Riccarton and the Rhodes brothers at Purau supplied goods (vegetables, dairy produce and mutton). All heavy luggage had to be taken by small boat around to the Estuary and up the Avon to Christchurch. Other lighter luggage was carried over the Bridle Path.

The first ‘selection days’ to ballot sections of land in the new towns were held in February 1851. The most popular town sections at first were those in Lyttelton.

Gradually the new arrivals moved over the Port Hills to Christchurch, and the town there grew.

Canterbury ‘firsts’ in 1851

| 6 January | First school opened in Lyttelton by the Reverend Henry Jacobs. |

|---|---|

| 11 January | First issue of the Lyttelton Times. |

| 18 January | First bank (Union Bank of Australia) opens in Lyttelton. |

| February | First bridge across the Avon (a footbridge) at Worcester Street. |

| 3 April | George Gould opens first shop in Christchurch. |

| April | Collegiate Grammar School opens in Lyttelton (later Christ’s College). |

| May | Ferrymead ferry service begins. |

| 20 July | First church - later dedicated as St Michael and All Angels in 1859. |

| 27 September | First drowning in the Avon (victim probably drunk). |

| November | White Hart opens - first hotel. |

| 16 December | Canterbury’s anniversary celebrated. |

see also the Christchurch Chronology

Towards independence

Within a year eight chartered Canterbury Association ships and another seven privately backed ships had arrived, bringing the population of the settlement to three thousand.

Many new arrivals did not stay in town, but moved out onto the plains, where the land was good for sheep and cattle farming. Already Wakefield’s plan for a small farming community was no longer possible, and Godley managed to get the rules for leases of rural land changed so that larger blocks could be turned into ‘runs’. Sales of wool grew.

Early in 1852 news of the Australian gold rushes attracted young men from the Canterbury settlement. Without their labour, the development of public works, such as roads, slowed over the next three years.

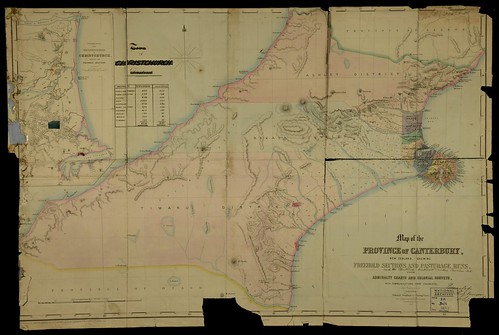

On 30 June 1852 the New Zealand Constitution Act was passed in England. New Zealand was divided into six provinces, each with their own administration, including an elected Superintendent.

The Canterbury Association ceased to exist from 30 September. Godley was invited to become Superintendent, but refused as he had decided to return to England.

Canterbury — a province

Under the new provincial system, Canterbury’s first superintendent was James Edward Fitzgerald, elected on 20 July 1853.

During the time he was superintendent, the sale of the back-country runs gave the Provincial Council a regular source of money.

Canterbury prospered in these years, with wool exports steadily increasing the amount of money available in the province.

![Cathedral, Cathedral Square [ca. 1888]](https://christchurchcitylibraries.com/Heritage/Photos/Disc1/IMG0048.jpg)

Transport problems

Because there were still big problems getting heavy luggage from Lyttelton to Christchurch, Fitzgerald tried to get the road to Sumner by way of Evans Pass completed.

In 1854 the Provincial Council agreed to give money to complete the road. On 24 August 1857 Fitzgerald finally drove his dog-cart over the road to Lyttelton. It was still a difficult road, which not many people were prepared to drive over.

Building the Lyttelton tunnel

The new Superintendent after Fitzgerald was William Sefton Moorhouse. Connecting the city and port was still a problem, and Moorhouse’s solution was to build a railway tunnel through the Port Hills to link Christchurch and Lyttelton. The Provincial Council finally agreed, and work began in 1860, coming to an early halt when harder than expected rock was struck during tunnelling.

Moorhouse brought in a new contractor and work on the tunnel began again. In May 1867 the two ends of the tunnel (Heathcote and Lyttelton) met exactly in the middle. On 9 December 1867 the tunnel was officially opened as New Zealand’s first rail tunnel.

While the talk about the building of the rail tunnel had been going on, New Zealand’s first passenger train service had started operating along a line from the Ferrymead wharf to Christchurch from 1 December 1863. This line later met up with the tunnel line, and extended south to the Selwyn River, with plans for a northern line to Rangiora.

The boom years

Canterbury’s growing wealth and prosperity during the boom years of 1857-64 had a big effect on the city. More banks opened Christchurch branches (Bank of New South Wales in 1861, Bank of New Zealand in 1862, and the Bank of Australasia in 1864).

New Zealand’s first telegraph opened in July 1863 between Christchurch and Lyttelton.

The city’s newspapers, the Lyttelton Times and The Press, were well established, with Samuel Butler writing for The Press while farming at Erewhon in the upper Rangitata.

Christchurch Hospital opened in 1862, and New Zealand’s first medical association was founded by Christchurch doctors in 1865.

The Horticultural Society was formed in 1861, and the Canterbury Agricultural and Pastoral Association held its first show in 1863.

The city’s first proper theatre, the Royal Princess Theatre, was opened on 26 December 1863.

After the death of John Robert Godley in 1861 in England, it was decided to erect a statue of him in Cathedral Square, in recognition of his status as leader and founder of the Canterbury settlement. This statue was unveiled in August 1867, and was the first public statue erected in New Zealand.

Christchurch becomes a municipal district

In 1862 Christchurch was made a municipal district, and John Hall elected the first chairman of the Municipal Council. This council introduced street lighting in June 1862, and sank the first water well in February 1864.

The Provincial Council buildings in Durham Street, designed by Benjamin Mountfort, were finally finished in November 1865.

In 1855 assisted immigration, or the payment of the fare of selected workers or emigrants, had begun again to Canterbury. The Provincial Council took over what had earlier been the role of the Canterbury Association and appointed an agent in England to select the emigrants. Between 1863 and 1864 over 6,000 new settlers came to Canterbury.

For a short time at the end of the 1860s wool prices fell and new immigrants had problems finding work. The ‘Great Canterbury snowstorm’ in July 1867 brought huge stock losses for Canterbury farmers (Lady Barker and her husband Frederick Broome amongst them). But the economy improved again in the 1870s.

New buildings

One of the signs of this prosperity was the increase in the number of public buildings in the city.

The first of these buildings was the Canterbury Museum, designed by Benjamin Mountfort and built in 1870. The Director of the museum was the geologist Julius Von Haast, who had used the discovery of a large number of moa bones in a swamp in Glenmark to swap moa skeletons for specimens from museums throughout the world.

Canterbury College (of the University of New Zealand) moved into new buildings opposite the Museum in 1877. The new Christchurch Boys’ High School shared the same block, and the Normal School in Cranmer Square opened in 1876, becoming New Zealand’s first teachers’ training college a year later.

The city still did not have its cathedral. The foundation stone had been laid in 1864, and the foundations finished in 1865 before the money ran out. Bishop Harper promised £50 a year from his salary towards the building fund. Others followed his example and by 1873 the building had started again. The tower and main part of the cathedral were finished by 1881, and although the rest was not completed until 1904, from the 1880s Christchurch was known as the ‘Cathedral City’.

Health and the city

The increase in the number of people living in the city led to serious public health problems. From 1872-75 there were epidemics of diptheria and whooping cough every year, and in the typhoid epidemic of 1875-76 152 people died in Christchurch. These diseases are all diseases of poverty - poor food and unhealthy living conditions.

Christchurch in 1876 was a polluted city. It had a good supply of artesian water from huge reserves of water deep under the city, but the waste of the city ran into the Avon and Heathcote rivers. Kitchen waste and chamber pots were emptied into channels running along the sides of the streets, and manure from the animals that provided the transport in the city just added to the problem.

A system of drains was needed but the iron pipes had to come from overseas and were expensive. Christchurch had to wait until the 1880s for an underground sewerage system, but it was the first city in New Zealand to have one.

End of a provincial era

In November 1876 the different provincial councils throughout New Zealand were replaced by a system of town boards, boroughs, road and harbour boards.

Canterbury had been one of the more successful provinces. By 1876 the city of Christchurch had a population of over 12,000 in the central city and another 10,000 in the suburbs.

1876 - 1900: important events and developments

| 1876 | The new Christchurch Drainage Board decided to install a system of sewers in the central city. Building began in 1879, and the system started pumping in 1882. |

|---|---|

| 1877 | Land boom in Canterbury, followed by a depression in the 1880s. New Christchurch railway station opened. A railway line now extended north to Amberley. By 1878 it had reached Dunedin in the south. |

| 1879 | New Zealand’s first rugby union formed in Canterbury. Lancaster Park opened in 1881. |

| 1880 | Steam trams began operation from Cathedral Square to the railway station. |

| 1881 | First telephone exchange in New Zealand opened in Christchurch. An earthquake damaged the spire of the not yet completed cathedral. |

| 1882 | Canterbury Frozen Meat Company set up. |

| 1883 | February: Belfast Freezing Works began operation. First shipment of frozen meat from Canterbury in April 1883. |

| 1885 | Women’s Christian Temperance Union formed. It became involved in the women’s suffrage campaign under the leadership of Kate Sheppard. |

| 1887 | Canterbury Show moved to Addington Showgrounds and the week of the show became known as ‘Carnival Week’. |

| 1888 | The spire of the cathedral damaged in an earthquake for the second time. |

| 1891 | Ballantynes became the first store in Christchurch to be lit by electricity. |

| 1893 | Ernest Rutherford gains an MA in mathematics and physics at Canterbury College. |

| 1894 | New Zealand Cricket Council formed in Christchurch. First New Brighton pier opened. |

| 1896 | District Nursing Association formed by Nurse Maude. |

| 1897 | Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee celebrated in Christchurch. |

| 1900 | Canterbury celebrated its jubilee (50 years). |

see also Christchurch Chronology

Sources

- Bateman New Zealand encyclopedia, 5th edition. David Bateman: Auckland, N. Z., 2000.

- The book of New Zealand women, edited by Charlotte Macdonald et al. Bridget Williams Books: Wellington, N. Z., 1991.

- Dictionary of New Zealand biography, Vol. 1, 1769-1869; Vol. 2, 1870-1900. Allen & Unwin , Dept. of Internal Affairs: Wellington, N. Z., 1990-2000.

- A history of Canterbury, vol. II. Whitcombe and Tombs Ltd.: Christchurch, N. Z., 1972.

- New Zealand’s heritage, Vol. 2. Hamlyn: Wellington N. Z., [1971-73].

- Ogilvie, Gordon. Pioneers of the plains: the Deans of Canterbury. Shoal Bay Press: Christchurch, N. Z., 1996.

- Rice, Geoffrey W. Christchurch changing: an illustrated history. Canterbury University Press: Christchurch, N. Z., 2000.

- The Reed dictionary of New Zealand place names, Reed Books: Auckland, N. Z., 2002, p 73.

Related pages

- Johannes C. Andersen, The Mission of the "Britomart" at Akaroa, Transactions of the New Zealand Institute volume LII, 10 June 1920